Once the airfield had been built (Part 4), it was occupied by ground and later air forces, and became operational. However, the process by which it was developed, was not haphazard, nor was the architecture of its buildings. Designed to meet specific needs, the airfields of Britain were built using local knowledge, materials and in many cases architectural design.

Airfield Architecture

Any of these airfield developments had to be in line with guidelines laid down by both the Royal Fine Arts Commission and the Society for the Preservation of Rural England, hardly what you’d want in such difficult times! These restrictions however, would initiate a building design that would initially be both functional and aesthetically pleasing, with standard designs varying only through local conditions (suppliers of local brick for example). In the early schemes a ‘Georgian’ style of architecture was chosen for all permanent brick buildings, distinguished by their pillars and ornate archways, often seen on the entrances to Officers Quarters.

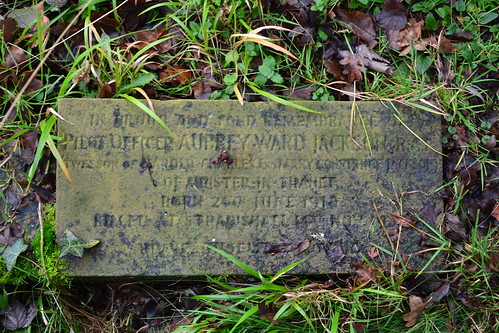

The Officers Quarters at RAF Stradishall were reflective of the types built during war-time under Scheme A

Standard designs allowed for replication across numerous airfields, the idea being an officer could lift his room from one site and drop it directly on another. RAF West Malling, (built under Scheme M), reflecting this with Stradishall, (Scheme A), above.

All buildings were constructed from brick with roofing tiles chosen accordingly for the local conditions. As the schemes progressed and brick became scarce, concrete was used as a cheap and strong substitute, certainly for technical buildings but less so for administration and domestic structures.

As each scheme was replaced, any previous buildings would have remained (some modified to the new standard), thus some sites will have had a range of building types, often leading to confusion and a mix of architectural styles. The accommodation areas themselves changed too. In the early war years and as the awareness of air attack increased, accommodation was built away from the main airfield site and outside of the airfield perimeter. Classed as either ‘dispersed’ or ‘non-dispersed’, they were identified by the location of these domestic sites, where ‘non-dispersed’ were within the perimeter, and dispersed were beyond the main perimeter area of the airfield.

The changing face of Barrack Blocks. A Type Q Barrack block at RAF Upwood, built to design 444/36, to accommodate 3 NCOs and 68 aircraftsmen. Compare this flat-roofed, expansion period building to the later Nissen hut.

In these early stages little consideration was given to air attack, and so ‘non-dispersed’ sites were still being constructed at the beginning of the war. The benefit of these sites being that all personnel were in close proximity, general accommodation buildings often being built around the parade ground, and with all the amenities under one roof. These sites also saw the segregation between officers, sergeants and other ranks along with separate married (many with servants quarters) and single quarters. However, with the outbreak of war and as a result of austerity measures, the building of separate married quarters ceased. Examples of these early non-dispersed designs include: Stradishall, Marham, Tern Hill, Waddington and Feltwell.

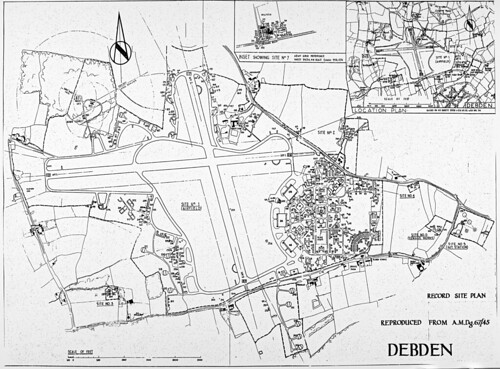

RAF Debden, a non-dispersed site where accommodation and administrative areas were collectively close to the main airfield site within the outer perimeter (IWM17560).

The layout of these barrack blocks, took on the familiar ‘H’ shape, a design that replaced the initial ‘T’ shape of the post First World War and inter-war years. The ‘H’ Block became the standard design and gave a distinct shape to accommodation blocks on these prewar non dispersed airfields.

As the awareness of the dangers of non-dispersed designs became all too apparent, dispersed sites became the norm, where domestic areas were located a good distance from the main airfield site. Dispersed accommodation could have many sites, depending largely upon the nature of the airfield (Bomber, Fighter etc), when it was built and whether it was operated by the RAF or USAAF. In these later dispersed schemes, domestic sites became more temporary in nature, whilst some remained as brick, many were built as prefabricated units often as Nissen or Quonset style huts, often due in part to the shortage of brick for building and the speed at which they could be erected.

With the changes in dispersing accommodation blocks away from the main airfield, safety increased but both administrative and operational effectiveness noticeably dropped. It was going to be a fine balance between keeping a safe distance and achieving maximum effectiveness.

A typical dispersed site showing the accommodation areas dispersed well away from the main airfield (bottom left). RAF Andrews Field (IWM UPL17532)

Depending upon local topography, these domestic areas could be situated as much as two miles from the airfield site, wooded areas being utilised where possible to hide the location of huts; blocks were randomised in their position to break up the appearance of housing, and pathways weaved their way round the sites to reduce their visual impact. In most later airfields, a public road would separate the technical and accommodation sites, with as many as thirteen or fourteen sites becoming common place.

The separation of WAAFs from RAF communal quarters also ceased, men and women now allowed to mix rather than having the separate sites for each. As a result many post 1942 sites had fewer dispersed sites then those of pre 1942.

The design of the technical areas also took on a new look. The prewar practice of squadrons offices being attached to the hangar was dropped, these also being placed away from the main technical site, dispersals for ground crew or waiting pilots were spread about the perimeter so airmen could be closer to the aircraft but far away enough to be safe in the case of attack. This led to a number of buildings appearing on the outer reaches of the airfield, along perimeter tracks and near to hardstands, often these were brick, small and square, others more temporary.

Further changes occurred with the reduction in available materials. These changes have given rise to a wide variation in building design, again many airfields having a variety of buildings using different materials.

Initially, buildings built of brick were strong and commonplace, but as this became both scarce and time-consuming to build, alternative forms were found. Timber followed on, but it too proved to be time-consuming to manufacture, and by 1940 acutely rare also.

A range of materials were looked into, using a mix of timber and concrete, plasterboard and concrete, but they were all below the Air Ministry standard. Even so, many were accepted as design alternatives and used in temporary building construction.

1940 saw the return of the 1916 designed Nissen hut, a curved hut that bolted together in widths of 16, 24 or 30 feet. A cold but effective hut it was commonplace on many airfields as both accommodation huts and technical huts, many being sold post war, and ending up in farmer’s fields many miles from the nearest airfield. With the arrival of the USAAF in 1942-3, they brought with them the Quonset hut, bigger in design than the Nissen, they are mainly distinguishable by their curvatures, the Quonset being semi-circular to the ground whilst the Nissen gave a 210o curvature. This extra curvature gave greater use of ground space, but lacked in overall space compared to it US counterpart.

Even this material became in short supply, metal being scare and urgently required for the building of military hardware. In 1942 the Ministry of Works took over control of hut design, manufacture and supply, and various new designs were brought into play. Asbestos became popular again, with the US being able to supply large quantities of the material. Uni-Seco Ltd, Turners Asbestos and Universal Handcraft being examples introduced at this time.

The final design to be used, was that of the Orlit, a reinforced concrete panel and post design that slots together to form the walls and roof. Also know as the British Concrete Federation (BCF) design they were quick to erect and lasted from many years. This type of design was used for emergency housing in the post war period and has since proven to be degrading to the point that some of these properties have been condemned.

Thus the architecture of airfield buildings took on many guises, from permanent brick designs, through timber, timber and plasterboard mixes, various metal design, asbestos and finally concrete, all of which gave a change in shape and design examples of which could appear on many airfields. The most common surviving examples today being the Nissen hut.

In the next section we shall look at the runway, the very heart of the airfield and often the defining factor in its designation.