In Trail 39 we turn south once more and return to Suffolk, to the southern most regions of East Anglia, to an area known for its outstanding beauty and its stunning coastline. It is also an area rich in both Second World War and Cold War history. Perhaps better known for its fighter and light bomber stations, it was also the location for several heavy bomber bases, each one with its own fascinating story to tell.

We start off this trail at the former site of American base at RAF Framlingham.

RAF Framlingham (Station 153)

RAF Framlingham is actually closer to the village of Parham than it is the town of Framlingham, hence it was also known as RAF Parham – a name that it became synonymous with. Built as a class ‘A’ bomber station its official American designation was Station 153.

Building work commenced in 1942, and as with most large bomber stations it was designed to the Class A specification to include: three concrete runways (one of 6,400 ft and two of 4,400 feet in length), an adjoining perimeter track that linked fifty ‘pan style’ dispersals; two T-2 hangars (one to the west with the technical site and one to the south-east) and accommodation for some 3,000 personnel dispersed in 10 sites to the south-west of the airfield. A further sewage treatment plant dealt with the site’s waste.

The main runway ran east-west and to the eastern end sat the bomb store, a large area that included: a pyrotechnic store, fusing point, incendiary store and small arms store – all encircled by a concrete roadway.

Part of the Perimeter track at the southern end of the airfield. To the right was the crew rest rooms, locker and drying rooms.

The administration site sat between the main technical site and accommodation areas all located to the south-west side of the airfield.

Opened in 1943, the first residents were the B-17s of 95th Bomb Group which consisted of four bomb squadrons: the 334th, 335th, 336th and the 412th. Flying a tail code of a square ‘B’ they initially formed part of the 4th Bomb Wing, changing to the 13th Combat Wing, 3rd Air Division of the Eighth Air Force in September 1943 following the reorganisation of the U.S. Air Force in Europe.

Following their inception and constitution on 28th January 1942 and subsequent activation in June, they moved from their training ground at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, through Oregon, Washington and eventually to Rapid City Air force Base in South Dakota. They began their move across the Atlantic in the spring of 1943, taking the southern route via Florida arriving at Alconbury and then moving on directly to Framlingham in early May/June that year. It was whilst stationed at Alconbury though that they would have their first few encounters of the war, and they would not all be plain sailing.

On May 27th, 1943 just 14 days after their first mission, ground crews were loading 500 lb bombs onto a 334th BS B-17 ’42-29685′ when the bombs inexplicably detonated, the Alconbury landscape was instantly turned to utter carnage and devastation. The blast was so severe that it killed eighteen men (another later died of his injuries), injured twenty-one seriously and fourteen others slightly. The B-17 involved was completely destroyed and very little of its remains could be found in or around the huge crater that was left deep in the Alconbury soil. Three other aircraft, 42-29808, 42-29706 and 42-29833, all sat within 500 feet of the explosion, were severely damaged and subsequently scrapped. In total, fifteen B-17s were damaged by the blast, it was a major blow to the 95th and a terrible start to their war.

There then followed a transition period in which the group moved to Framlingham. During this time operations would continue from both airfields leaving the squadrons split between the two bases. The first few missions were relatively light in terms of numbers of aircraft lost, however, on June 13th 1943, they were part of a ‘small’ force of seventy-six B-17s targeting Kiel’s U-boat yards. This was to be no easy run for the 95th, a total of twenty-two aircraft were lost on this raid and of the eighteen aircraft who set off from Framlingham in the lead section, two aborted and only six made it back. In one of the lead planes, was the newly appointed Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest as observer. Riddled with bullet holes, his aircraft plummeted from of the sky with the majority of its tail plane missing and one of its engines ablaze. His body was never found and he became the first U.S. General causality of the war. In total, the raid resulted in 236 crewmen being listed as either missing, killed or wounded – this would be the 95th’s heaviest and most costly mission of the entire war.

Two days after this mission the group would depart Framlingham and move to RAF Horham a few miles north-west, where they remained for the remainder of the war. The majority of the crews would probably be pleased to move away leaving behind many terrible memories and lost friends. However, the tide would turn and they would go on to gain a remarkable reputation and make a number of USAAF records. They would be the only Eighth Air Force group to achieve three Distinguished Unit Citations (DUC), and be the first group to bomb Berlin. They also claimed the highest number of enemy aircraft shot down by any bomb group and they would be the group to suffer the last aircraft loss (on a mission) of the war – all quite remarkable considering their devastating introduction to the European Theatre.

As the 95th departed Framlingham so moved in the 390th BG.

The 390th BG like the 95th and 100th were part of the 13th Combat Wing, 3rd Air Division. They too were a new Group, only being formed themselves early in 1943. The 390th BG was made up of four B-17 bomb squadrons: the 568th, 569th, 570th and 571st, and at initial full strength consisted of just short of 400 personnel. They formed part of the larger second wave of USAAF influxes who were all new recruits and whose arrival in the U.K. would double the size of the USAAF’s presence overnight.

Old hands of the Mighty Eighth, took great pride in teasing these new recruits whose bravado and cockiness would soon be knocked out of them by the more experienced Luftwaffe fighter pilots.

The 390th would create quite a stir in the Suffolk countryside and not just because of their ‘smooth taking’, ‘endless supply of chocolate’ and ‘upbeat music’. Up until now, the ‘smuggling’ of pets into American airbases had been by-and-large ignored, but with the 390th came a Honey Bear, a beast that quite frequently escaped only to be confronted by rather bemused locals! There would be however, despite all this frivolity, no rest period for the crews, and operations would start the 12th August 1943, less than a month after they arrived.

B-17s of the 390th BG over RAF Framlingham (IWM)

The latter parts of 1943 saw a lot of poor weather over both the U.K. and the continent, and this combined with the heavy use of smoke screens by the Germans, prevented large numbers of bombers finding their targets. As a result, many crews sought targets of opportunity thus breaking up strong defensive formations. The eager Luftwaffe pilots made good use of this, taking advantage of broken formations and poor defences. As a result, the bombers of this new influx would receive many heavy casualties and August 12th was to become the second heaviest loss of life in the American air war so far.

1943 would be a busy time for the 390th, within a few days and on the anniversary of the U.S. VIII Air Force’s first European operation, they would attack the Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg, a mission for which they would receive their first Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC).

The operation would be a blood bath. On that day 147 B-17s took off with the 390th forming the high squadron in the first formation. For over an hour and a half, multiple fighters of the Luftwaffe attacked the formations which were split by delayed arrivals, and large gaps in the formation. Compounded with this was the fact that the escorting P-47s had to return home leaving the formations largely undefended. With no fighter escort the bombers became easy prey and the numbers of blood-thirsty attacks increased. The rear and low formations of the force were decimated and departing P-47 fighter crews could only look on in horror.

Over the target, skies cleared and bombing accuracy was excellent, but it was the 390th that would excel. Of the seven groups to attack, the 390th manged to get 58% of its bombs within 1000 ft of the target and 94% within 2000 ft, a remarkable achievement for a fledgling group. Flying on, they passed over the Alps and across Italy onto North Africa where they landed – their first shuttle mission was complete. The run in to the target and subsequent journey to North Africa would create multiple records; two B-17s, one of which belonged to the 390th, sought sanctuary in neutral Switzerland, the first of any group to do so. But the journey across Europe had been difficult and it would cost the lives of six B-17 crews – it had truly been a hard-won DUC.

Two months and some 20 missions later, they would repeat this epic achievement. On October 14th 1943, they took part in the second major attack on Schweinfurt, a target whose name alone put the fear of God into many crews. The route that day would take them across some of the most notorious Flak black spots, Aachen, Frankfurt, Bad Kissingen and Schweinfurt itself. On top of that, Luftwaffe fighters would be hungry for blood, many crew members knew this would be a one way trip.

Take off was at 10:00am, and the Third Air Division would provide 154 aircraft, but again due to mechanical problems and poor weather, the formation were scattered across the sky and defences were weak. As they crossed the channel enemy aircraft were few and far between, giving false hopes to rookie crews who were cruising 20,000 feet above the ground. Eventually at around 1:00pm the escorts left and the waiting Luftwaffe crews stepped in. All hell broke loose. Rockets, timed bombs and heavy machine gun fire riddled the B-17 formations – Schweinfurt was going to live up to its reputation. After fending off relentless attacks by the Luftwaffe, the formation reached their target and all 390th aircraft managed to bomb with an accuracy of 51% of the MPI (Mean Point of Impact). For this they received their second DUC – the newbies were rapidly becoming masters of the air.

1943 would draw to a close, and the optimism of many ‘successful’ raids over the Reich would bring the dawn of 1944. Big week in February saw the massed attacks on the German aircraft production factories, and in March, the 390th attacked Berlin. During this raid B-17 ’42-30713′ “Phyllis Marie” made an emergency landing only to be captured intact by the Luftwaffe and flown under KG200. It was later found in Bavaria.

Other major targets for the 390th this year included Frankfurt marshalling yards, Cologne, Mannheim, the navel yards at Bremen and the oil refineries at Mersburg. In 1944 the 390th softened the German defences along the Atlantic coast just fifteen minutes before the invasion force landed in June. They followed up the advance by supporting the allied break out at St. Lo.

During August 1944, the 390th flew a round mission that took them for the second time to a Russian airfield. After refuelling and rearming, they attacked the oil refineries at Trzebinia (later famed with the POW’s ‘death march’ across western Europe) and then back to Russia. Three days later they flew to North Africa, depositing high explosives in Romania, and then four days after that, the return trip to Framlingham bombing Toulouse on the way.

The cold winter of 1944 would become well-known for its snow and ice, a period in which almost as many aircraft were lost to ice as to enemy action. On December 27th, the cold would claim B-17 ’42-107010′ “Gloria-Ann II” of the 569th BS. A build up of ice would bring her down within a minute of taking off and the ensuing explosion of fuel and bombs would cause a fire from which nine crew members would perish. Houses in the vicinity of Parham were also damaged but there were no local casualties and the aircraft would be salvaged and reborn as “Close Crop“.

Battle damage was often severe, here B-17G #42-97849 “Liberty Bell” of the 570th BS, shows extensive damage to her tail section. (IWM)

In the early months of 1945 the Ardennes was also gripped in this terrible fog and cold. The 390th took off in support of the paratroopers locked in the Belgium forests, bombing strategic targets beyond the Ardennes, they cut German lines preventing further supplies reaching the front.

By 1945 it was no longer a rare occurrence for bombers to have exceeded the 100 mission milestone, for the crews however, it was a target to avoid. For the 390th, April 1945 would see the first US airman to surpass the 100 mission mark achieved solely whilst operating in the European theatre. Hewitt Dunn, acting as bombardier (Togglier) was the first US Eighth AF airman to surpass 100 missions in an operational span that started in January 1944 and that had seen him in virtually every position of an operational B-17, and over virtually every high risk target in occupied Europe – he was just 24 years old.

Gradually the summer sun came and with it clear skies. Allied air operations increased and soon the end was in sight for Nazi Germany, but air accidents and US losses would still continue. On landing his B-17 “Chapel in the Sky“, Murrell Corder ground looped his aircraft to prevent crashing into other parked B-17s. In doing so, he clipped the wings of “Satan’s Second Sister” severely damaging both aircraft, thankfully though, there were no casualties.

At the end of the war the 390th left Framlingham and returned to the United States. They had received two Distinguished Unit Citations, had the highest enemy aircraft claim of any unit on one single mission and reached the first 100th mission of any aircrew member. Their tally had amounted to 300 missions in which they had dropped over 19,000 tons of bombs. They had definitely earned their place in the Framlingham history books.

On departure, Framlingham was given back to the RAF who used it as a transit camp to help with the relocation of displaced Polish people. It was then closed in the late 1940s and sold back to the local farmer, with whom it remains today.

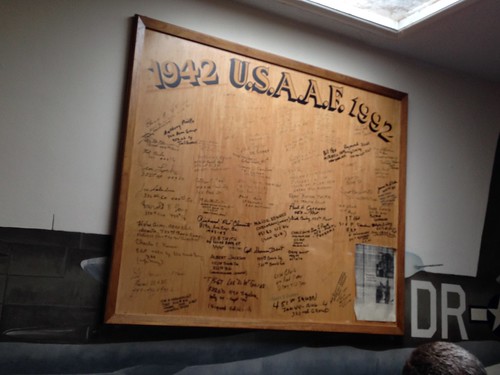

A small consortium of volunteers have manged to rebuild the control tower into a fabulous museum, displaying a wide variety of aircraft and airfield parts, and personal stories from those at Framlingham. They have also refurbished a couple of Nissen huts, recreating life in a barrack room as it would have been during the Second World War, and displaying articles and stories from the resistance organisation.

As for the airfield, much of the perimeter track remains as do long sections of the runways as farm tracks. The public road today passes through the centre of the airfield dissecting the technical area from the bomb store. From the northern most end a footpath allows you to walk along the north-western section of the perimeter track, currently used by a road repair company for storing stone chippings and lorries. The hardstands have been removed and piles of rubble contain evidence of drainage and electrical supply pipes. From the road at this point you can also see a small section of the main runway – now holding piggery sheds – which has virtually all been removed. From the western side of the perimeter track you can look along the north-west to south-east runway, a mere fraction of its former self, it is barely wide enough for a tractor let alone a heavily laden B-17 and her crew.

Returning to the museum front takes you along the widest part of this runway. A small section at almost full width, it gives you an indication of the 150 feet of concrete that makes up these great structures, and an insight into what they would have been like during the mid 1940s.

Behind the museum stands one of the hangars, this along with the tower are the two most discernible buildings left on site. Many of the accommodation buildings are now gone, and what is left is difficult to see. A footpath does allow access across the bomb store – now a wooded area, but if walking from the north, it is virtually impossible to park a car due to the very narrow and tight roads in the area.

Like many of Britain’s airfields Framlingham holds a wealth of stories in its midsts. The near constant roar of B-17s flying daily missions over occupied Europe are now whispers in the trees. The museum, a lone statue, gazes silently over the remains of the airfield offering views of ghostly silhouettes as they lumber passed on their way to a world gradually being forgotten. Framlingham and the 390th, have definitely earned their place in the world’s history books.

Whilst in the area, take a short trip to Framlingham town, below the castle, is St Michael’s church and above the door a 390th Group Hatchment in honour of those who served at Framlingham.

From here, we travel south-west toward Ipswich and stop at another USAAF base also with a fabulous museum. We go to RAF Debach – home of the 493rd BG(H).

Notes, sources and further reading.

*Photos exist of what appears to be a Type ‘J’ or ‘K’ hangar on the site. This does not appear on the airfield drawings however and its origin is as yet unknown.

A number of sources were used to research the history of RAF Framlingham and the 390th, they are highly recommended for further information. They include:

The 390th Memorial Museum website.

Veronico. N., “Bloody Skies“, Stackpole Books, 2014

Freeman, R., “The Mighty Eighth“, Arms and Armour Press, 1986

Freeman, R,. “The B-17 Flying Fortress Story“, Arms and Armour Press, 1998