In 2021, I was contacted by Mike Herring and Trevor Danks, regarding the story of 2nd Lt. John Crago who was based at RAF Kings Cliffe in Northamptonshire during World War 2.

It was sad tale of how one young man died in a tragic accident not long after arriving in the UK from the United States. Mike and Trevor kindly allowed me to reproduce the entire text with photos to share with you, my sincere thanks go to them both.

This is the story of 2nd Lt. John Walter Crago who tragically lost his life in an aircraft crash on 31st December 1943 whilst operating from Kings Cliffe airfield.

Firstly, however, let us look at his origins.

His grandparents were Harry and Bessie Crago who were born and lived in Cornwall on the SW tip of England. Harry was born in Liskeard in November 1858 and Bessie in Duloe in May 1862.

The surname “Crago” is quite common in that area. Cornwall had been a major source of tin and lead for many years and there were extensive mine works around the county.

After leaving school Harry worked in the mines from about the age of 12.

In 1878 Harry and Bessie, still unmarried, moved to the coal mining village of Wingate, near Durham, in the North East of England, where Harry worked as a coal miner.

In the early part of 1879 Harry and Bessie married at Wingate and by 1881 they were living at 13, Emily Street, Wheatley Hill, Wingate and had a one year old son with them – William.

As an aside the village of Wingate is well known to some people in Kings Cliffe. It was the home of the writer’s wife’s parents until their recent death and brothers and sisters still live there.

The coincidence increases as it is also the place where friends, Rodger Barker, living in Kings Cliffe, and Jim Vinales, managed to crash a Vulcan bomber in 1971, that had lost two engines. The crew fortunately survived. (see chapter one of “Vulcan 607” Corgi books).

In 1882 Harry and Bessie emigrated to the USA, by now having two children , and it is no co-incidence that they settled in Pennsylvania which was a significant coal mining area, Harry working there as a miner.

Their third child, Walter P Crago, was born at Houtzvale, P.A. on 16th August 1893. He is the father of the subject of this story.

In the US Census of 1910 16 year old Walter is shown as having no occupation, although his father and elder brother are working as miners.

In the 1920 US Census, Walter is married to Margaret K Crago and they have a one year old son, John Walter, born 5th April 1917 who is the subject of our story. His father’s marriage to Margaret does not seem to have lasted as by 1930 Walter has married Lorena C Crago (nee’ Curtis).

John Walter Crago is brought up in Philipsburg, PA, a small town of about 3000 people (twice as big as Kings Cliffe) which is situated about 200 miles due west of New York.

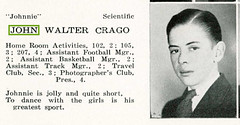

Our next glimpse of John W is in his High school Year book in 1934 when he was 17 years old.

Johnnie did one year in high school and was clearly keen on his sport as well as the local girls!

Six year later in the US Census of 1940 John’s father, Walter, is by then the part owner and bar tender of a restaurant/tap room in Philipsburg and John W is working for him.

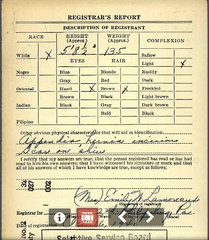

In Europe WW2 is in full flow and clearly the US is preparing for its possible involvement as John is signed on in the draft on 16th October 1940.

He is described on his draft form as 5’-8 ½” (1.74m) tall, weighing 135 pounds (61kg) with hazel eyes, light completion and brown hair.

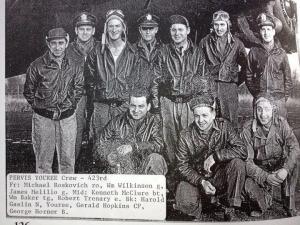

John trained to be an Army Air force pilot and joined the 55th fighter squadron, part of the 20th fighter group.

They arrived at Clyde in Scotland in August 1943, then travelled to their new base at Kings Cliffe in Northamptonshire, England. The 20th fighter group consisted of three squadrons of about 14 planes each – 55th, 77th and 79th.

The group was the first to fly the new P-38 Lightning escort, fighter ground attack air craft in combat in Europe.

There was insufficient room at Kings Cliffe for all of three squadrons and therefore 55 Fighter Squadron , of which John Crago was a member, were based at RAF Wittering, just two miles North of Kings Cliffe.

The P-38 Lightning had a somewhat chequered history in its’ early days. It had several recognised problems, but because of the needs in Europe for a powerful, high flying escort aircraft, the early ones were shipped out without those problems being resolved. They suffered from many engine failures, and instability in certain circumstances.

Of significance to our story is part of the Wikipedia article on the development of the P-38 which reads –

“Another issue of the P-38 arose from its unique design feature of outwardly rotating, counter rotating propellers. Losing one of the two engines in any two engine non centre line thrust aircraft on take-off creates sudden drag, yawing the nose towards the dead engine and rolling the wing tip down on the side of the dead engine. Normal training in flying twin engine aircraft when losing one engine on take-off is to push the remaining engine to full throttle to maintain airspeed. If the pilot did this on a P-38, regardless of which engine had failed, the resulting engine torque produces an uncontrollable yawing roll and the aircraft would flip over and hit the ground.”

The first mission for 55 squadron was on 28th December 1943 consisting of a sweep across the Dutch coast without encountering enemy aircraft. The mission summary report for that day reads –

28th December 1943

- 55th Fighter Squadron, 20th Fighter Group, Captain McAuley leading.

- 12 up at 1308 Down Wittering 1510

- Nil

- O 4 SWEEP

- To N. Nil

- Altitude over English coast mid-channel R/T jammed and remained so until mid-channel return trip. Landfall in, Wooderhoodf, at 1402. Altitude 20,000 feet. Light to moderate flak accurate for altitude over Flushing. Left turn and proceeded from Walchern to Noordwal 18 to 20,000 feet.

- Landfall out 1416 Noordwal. Weather clear all the way.

The second mission on the 30th December was more serious, escorting B-17 and B-24 bombers on an attack on a chemical plant near Ludwigshafen. The mission report for that day reads –

30th December 1943

- 55th Fighter Squadron, 20th Fighter Group

- 14 up 1121 at Kings Cliffe. Down 1500 Wittering.

- 3 aborts. Captain Jackson, Lt. Col. Jenkins – Radio. Lt. Sarros, gas siphoning.

- Bomber escort. Field order No. 210

- Nil

- Nil

- Nil

- Nil

- Landfall Ostend 24,000 feet at 1212. Climbed to 25,000 feet Brussels circled area 15 minutes. Proceeded to R/v with bombers. St. Menechoulde 25,000 feet at 1312. Reims 2 Me 109’s seen diving through bomber formation. Squadron left Bombers Compegiegne 1346. Encountered light flak Boulogne. Landfall out 1407, 24,000 feet. Clouds 6/10 over channel. 10/10 just inland. R/t ok.

The third mission was scheduled for 31st December and involved escorting bombers on an attack on a ball bearing factory at Bordeaux. John Crago was one of the 14 pilots of 55 squadron scheduled to be on this trip. He was temporarily based at RAF Wittering whilst suitable accommodation was built at Kings Cliffe and was flying from Wittering to Kings Cliffe to be briefed on the mission with the other pilots of 55, 77 and 79 Squadron who made up 20 Group. On arriving at Kings Cliffe he reported problems with his landing gear and did a low level fly past the control tower so that they could observe any obvious problem. As he approached the tower smoke was seen coming from his left hand engine.

He would have been flying slowly, close to stall speed, so that the tower had more time to observe any problem. Bearing in mind the reported problem with the P-38 flying on one engine the plane probably became uncontrollable. He clearly achieved some height as his eventual crash site was about two miles away at the village of Woodnewton. He did not survive the crash.

John Crago is buried at the Cambridge American Cemetery; plot A/5/22.

His was one of the bodies of American servicemen whose next of kin decided not to repatriate. One could conjecture that he was left to rest in the land where many generations of his forefathers had lived.

Mike Herring

Kings Cliffe Heritage

Sources:

Vulcan 607 by Rowland White, Corgi Books.

US Census 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940.

UK Census 1861, 1871,and 1881

Ancestry.com

Ancestry.co.uk

The American Air Museum – Duxford www.iwm.org.uk/duxford

2nd Air Division Memorial Library – Norwich www.2ndair.org.uk

Report from Woodnewton Heritage Group

New Year’s Eve this year marks the 75th anniversary of a tragic accident in Woodnewton which resulted in the death of an American pilot and brought the realities of the Second World War closer to the inhabitants of our village.

JOHN WALTER CRAGO

John Walter Crago held the rank of 2nd Lieutenant in the US Army Air Force. He died instantly in an accident on 31st December 1943 when his aircraft crash landed in Woodnewton, in the field known as Stepping End just beyond Conegar Farm.

Lieutenant Crago was born on 5th April 1917 in Phillipsburgh, Pennsylvania, the son of Walter P Crago and Margaret K Jones. He had enlisted in March 1942 and was a member of the 55th Fighter Squadron of the 20th Fighter Group. This Group was under the command of the 67th Fighter Wing of the Vlll Fighter Command of the USAAF. When he died he was 26 years old.

The circumstances leading to the accident on 31st December are recorded here in general terms only as told by former and existing residents of Woodnewton and supported by information from the Internet. It is not meant to be definitive.

The USAAF was assigned RAF Kings Cliffe in early 1943 and it was re-designated as Station 367. It was the most northerly and westerly of all US Army Air Force fighter stations. At that time RAF Kings Cliffe was a very primitive base, lacking accommodation and other basic facilities, so the Americans undertook an extensive building programme at the base during 1943. The 20th Fighter Group arrived on 26th August 1943 from its training base in California having crossed the USA by railway and then the Atlantic aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth on a five-day unescorted trip. The Group comprised three Fighter Squadrons; two of those Squadrons were based at Station 367 whilst the third, the 55th Fighter Squadron (Lieutenant Crago’s), was based at RAF Wittering whilst additional accommodation was being built at Kings Cliffe. The Group did not come back together at Station 367 until April 1944. Up to December 1943 the Group flew Republic P-47 Thunderbolt planes. With the arrival of their new Lockheed P-38 Lightening planes in late December 1943 the 20th Fighter Group entered fully into operational combat and was engaged in providing escort and fighter support to heavy and medium bombers to targets on the continent.

In the early morning of 31st December 1943 Lieutenant Crago was to fly from RAF Wittering to Station 367 to be briefed on his first combat mission – to provide escort protection on a bombing mission to attack an aircraft assembly factory at Bordeaux and an airfield at La Rochelle. This was to be just the 3rd mission by the fully-operational Group flying P-38’s. The planes of the 55th Squadron took off from RAF Wittering three abreast but unfortunately the right wing-tip of Lieutenant Crago’s plane struck the top of a search light tower on take-off. Lieutenant Crago must have lost some control of the aircraft but not it would appear the total control of the plane. He flew it from Wittering and was trying to get to Station 367. Unfortunately, he only got as far as Woodnewton.

The plane approached the village from the north-east, flying very low over Back Lane (Orchard Lane) and St Mary’s Church but crash landed in the field known as Stepping End just beyond Conegar Farm. Eyewitnesses said that the pilot discharged his guns to warn people on the ground that he had lost control of the plane and was about to crash. Wreckage from the plane was still visible in Stepping End in the 1950’s and a “drop tank” (for additional fuel) could also be seen in the hedge between King’s Ground and Checkers. A brief reconnoitre in November 2018 however found no recognisable evidence of the plane in the hedgerows around the fields.

Stepping End is the first open field – no hedges or fencing – on the right-hand side of the track from Woodnewton to Southwick. From Mill Lane, cross the bridge over the Willowbrook, and continue until the land begins to rise at the start of the hill. King’s Ground and Checkers are the next two fields on the right along the same track.

It is understood that 2nd Lieutenant Crago, whilst no doubt a qualified and proficient pilot, had had only 7 hours flying experience in the Group’s new P-38 Lightning at the time of the accident.

A memorial plaque to Lieutenant Crago was put up in St Mary’s Church to commemorate his death. The wording on this memorial faded over time however, and the plaque was replaced in 2001, although the wording on the two plaques is the same.

2nd Lieutenant John Crago is buried and commemorated at the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial (Plot A Row 5 Grave 22). His photograph can be seen at “www/20thfightergroup.com/kiakita”.

My sincere thanks go to Mike and Trevor for sending the text and pictures and for allowing me to share the sad story of Lt. John Walter Crago.

![USAAF personnel on the control tower at Thurleigh airfield [Z50-122-45]](https://bedsarchives.bedford.gov.uk/CommunityHistories/Thurleigh/ThurleighImages/USAAF%20personnel%20on%20the%20control%20tower%20at%20Thurleigh%20.jpg)