Bordered by Cambridge and Suffolk to the North, Hertfordshire to the west, London to the south and the North Sea to the east, Essex is a coastal county that boasts a diverse range of landscapes. Primarily commuter belt for London, it has a range of its own industrial giants, electronics and pharmaceuticals being prime employers of the area. It also has a long and diverse aviation history, hosting a number of wartime airfields some of which are still in use today – albeit under a different guise.

Following on from Trail 33 (Essex Pt. 1), we return once more to Essex to its northern borders to visit some of the airfields that can be found among its green fields and idyllic villages. We start off at the former airfield, RAF Castle Camps.

RAF Castle Camps.

Castle Camps lies straddling the borders of Cambridge and Essex, a small unassuming airfield, it was none the less home to thirteen operational units at some point in their wartime career. It was constructed early on in the war, in sight of an ancient Motte and bailey built by Aubrey de Vere, soon after the Norman Conquest. Itself quite a historic monument, there is evidence that dates the site back further to both the Saxons and Romans. This castle itself is known to be the largest Medieval fortress in the county, and dates back to the latter parts of the thirteen century*1. Originally known as Great Camps, and Camps Green, it is after this Castle that both the village and airfield gained their names.

Castle Camps housed a small number of aircraft types: Hurricanes, Beaufighters, Spitfires and Mosquitos all resided here, with some as detachments, but many as full squadrons. Even with increases in Squadron numbers, only one unit was ever formed here, that of 527 Squadron in 1943. However, that did not mean a posting here was by any means ‘quiet’.

Opening in the summer of 1940, it was designed as a satellite for nearby R.A.F. Debden and as such, both its accommodation and facilities were rudimentary to say the least. A grass airfield, with initially little more than tents for sleeping, it possessed a more ‘informal’ atmosphere than many of the R.A.F.’s other airfields.

No. 85 Squadron – a First World War unit that had only been reformed two years before war broke out – had been stationed in France to face the advancing might of the German army. Badly beaten and continuously moved around the many airfields of France: Merville, Lille, Mons-en-Chaussee and Boulogne, the squadron was completely decimated with only four aircraft from those originally sent out returning. In May 1940, these aircraft were pulled back to Debden to reform and re-equip. With detachments at both Martlesham Heath (A Flight) and Castle Camps (B Flight) they would be led by the soon-to-be-famous, Squadron Leader Peter Townsend, D.F.C.

85 Sqn would initially take on a regime of coastal patrols many starting in the early dawn sunlight and continuing on through until dusk. These repeated flights were undertaken using many new ‘green’ crews who were eager to get back at the enemy for defeats in France. Whilst those at Martlesham would be thrown into the deep end, the Debden and Castle Camps’ crews would find their time slightly less ‘strenuous’.

The CO of No. 85 Squadron, Sqn Ldr Peter Townsend, jumps down from Hurricane Mk I P3166 ‘VY-Q’ while being refueled at Castle Camps, July 1940. © IWM (HU 104489)

With many airmen arriving with less than 10 hours flying experience, it was vital they learn discipline and extreme vigilance whilst flying, and Townsend saw these flights as a way of achieving that. By the end of June 1940, the flights at Debden and Castle Camps had undertaken 505 hours of flying, of which only 25 had been recorded as ‘operational’.*2

The importance of this training was soon realised when on July 22nd 1940, Hurricane P3895 piloted by Pilot Officer John Laurence Bickerdike (s/n 36266), undershot the runway at Castle Camps. In the resultant crash, Bickerdike at just 21 years of age, was killed.

On August 13th, ‘B’ Flight departed Castle Camps and returned to Debden joining with ‘A’ Flight from Martlesham Heath. At last the squadron was together again and it wouldn’t be long before they would be moving on to pastures new, this time to Croydon, on the southern outskirts of London.

Other than an almost passing overnight stay in September, 85 Squadron wouldn’t return to Castle Camps until the war’s end in 1945.

Hawker Hurricane P2923 ‘VY-R’ of No. 85 Squadron. The Operational Record Books show this aircraft being flown by F/O R.H.A. Lee, D.S.O., D.F.C., at Castle Camps, August 1940. He was lost on the evening of August 18th 1940. Note the ‘temporary’ wooden airmen huts see note below. © IWM (HU 104510)

Whilst Debden remained busy – 85 Sqn making a straight swap with 111 Sqn – Castle Camps was quiet. The next users would be 73 Squadron in early October 1940.

Moving from the night training duties of Church Fenton, 73 Squadron had themselves been more successful in France than 85 Sqn. Using Hurricanes in this night fighter role though proved to be a costly mistake, as they were wholly unsuited and casualties were high in these early flights. By the end of October into early November, operational sorties has ceased as preparations were made to transfer the entire unit, via HMS Furious, to Heliopolis.

With this departure, Castle Camps fell operationally quiet again, and it was decided to upgrade both the airfield’s accommodation and flying facilities.

Three runways were built all covered with tarmac: the main running south-west to north-east of 1,900 yards, with a secondary and third runway of 1,600 yards and 1,070 yards respectively. Both the main and third runways were later extended, the main to 2,600 yards and the third to a more standard 1,100 yards. Sixteen hardstands were provided for aircraft dispersal as hangars were not yet added, but a Bellman and eight blisters were later erected.

Accommodation would be provided for 1,178 male and 184 female staff, 1,179 of which were ordinary ranks. The original temporary wooden huts (possibly Laing huts) were supplemented with ‘improved’ Ministry of Supply (MoS) huts. These differed in that they had canted sides as opposed to vertical sides normally found in these types of accommodation huts. Three of these huts are believed to survive today in a very much modified condition and used for agricultural purposes, a big change from the time they were used by the W.A.A.F.s of Castle Camps.

Once construction was near complete, operational units would again return. On the 17th December 1941, 157 Squadron (formed at Debden three days earlier) were informed of their immediate departure to Castle Camps, which would now become a self-serving airfield. The move, which would involve 3 Officers, 34 N.C.O.s and a few airmen, began that day, with ground crews from 3081 Servicing Echelon accompanying them on the next day. A range of other staff began arriving during the course of the closing days of 1941.

However, the running of the airfield and squadron was badly hampered by the lack of an N.C.O Disciplinarian and Clerk, and by the fact that officers were having to travel back to Debden for accommodation, as it was not available yet here at Castle Camps – the situation was far from ideal.

As Christmas approached, morale began to decline. Influenced by a number of factors it was primarily due to both the lack of work and the isolation of the Castle Camps airfield; the continuing influx of ground personnel also hindered the camp, as by now, it was beginning to put a strain on the lack of completed accommodation. On the 21st, Wing Commander Gordon Slade and Pilot Officer Truscott, his observer, both arrived on posting from 604 Squadron at Middle Wallop. Joining Slade at Castle Camps a month to the day, would be Sqn. Ldr. Rupert Clerke, formerly of No.1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (P.R.U.), who flew the first operational Mosquito sortie the previous year on 17th September to Brest. It would be almost a year later on September 30th 1943, that Clerke would fly the first Mosquito day sortie, a flight that resulted in the loss of a Junkers Ju 88 off the Dutch coast.

With little work to do, ‘Normal Squadron Routine‘ was repeatedly entered into the operations records, and so to help boost this flagging morale, the 25th December, was declared a general holiday for all staff who had were said to have a “real good Christmas feed and a good time was had by all“, no doubt a welcome break to the monotony that had preceded the season’s festivities.*3

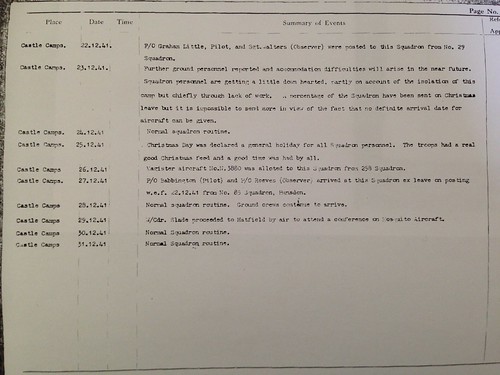

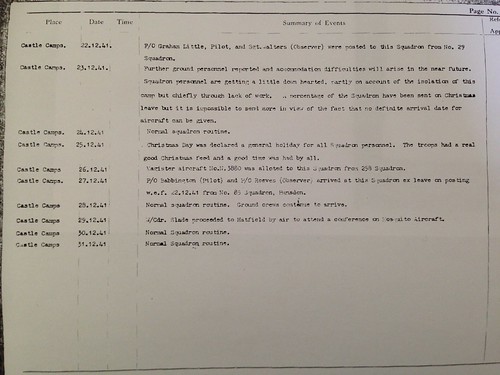

The entries for December reflect the poor morale and the regular Normal Squadron Routine that was becoming ‘routine’. Note the arrival of Sgt. Walters, His name appears in the Roll of Honour – see below. (AIR 27/1045)

Boxing day would see the first aircraft to arrive, bringing new hope to the squadron. A Magister (N3880) was not what had been hoped for, but at least it was taking the squadron in the right direction. More ground crews arrived and more “normal squadron routines” occurred. On the 29th, W/Cdr. Slade travelled to Hatfield to attend a conference on the new Mosquito and in the new year, Air Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas (A.O.C. in C. Fighter Command) arrived with the Debden Sector Commander Group Captain Peel. A full inspection of the airfield took place, which coincided with twelve airmen transferring on attachment to 32 Maintenance Unit (M.U.) at St. Athan, where the new Mosquitos were being “fitted and tested”.

A flurry of activity over the next few days saw W/Cdr. Slade travel to both Boscombe Down, and St. Athan – at last things seemed to be happening.

Finally, on the 26th January, 1942 the first Mosquito would land, flown in by W/Cdr. Slade. Slade, who had flown the prototype Mosquito previously at Boscombe Down, brought in a dual control aircraft (W4073) but hopes of more aircraft were soon dashed as this was sadly the only model to arrive for some time.

For the remaining weeks bad weather hampered work on the airfield, and with workshops, decent accommodation and tools still lacking, Castle Camps was rapidly becoming a thorn in the Squadron’s side.

Further ground staff came and went, Mosquitos were ferried between Hatfield and St. Athan by pilots of 157 sqn, for fitting of electronic equipment, W/Cdr. Slade and five officers moved in to dispersed accommodation at a large mansion known as “Walton House” near Ashdon, 3 miles from the airfield.

The village sign at Castle Camps reflects the ever-present Black Mosquitos of 157 Sqn at the airfield.

On February 22nd, a Beaufighter II arrived, flown by W/Cdr. Ashfield, and by the end of the month more than a dozen Mosquitos had been transferred for modification to St. Athan. There was now a light at the end of the cold, dark tunnel. Staffing was now up to 16 Officers, 12 N.C.Os and 160 other ranks; some of the accommodation site drainage had been sorted, officers showers and baths were now working, and the N.A.A.F.I was at last open and providing entertainment for the staff. The first football match was played between the squadron and the works flight, a resounding thrashing saw the squadron winning 6 – 0.

Over the next few weeks facilities would gradually improve, the weather began to get warmer, and the signs were that more aircraft would soon arrive. On March 9th 1942, the first two operational Mosquitos arrived at Castle Camps, and what a welcome sight it must have been.

The first to arrive were W4087 and W4098, neither were yet fully fitted, but that wouldn’t dishearten the staff at Castle Camps, at least things were now moving. Over the next few days a large number of Mosquitoes would arrive, these NF.IIs were Airborne Interception (AI) equipped night fighters, armed with four .303in Brownings and four 20mm cannon – all very potent weapons of the night war.

By March 29th 1942, 157 squadron had to its name: 14 Mosquitos, 1 Beaufighter (fully equipped), 1 dual Mosquito, 3 not fully equipped Mosquitos, and 2 Magisters. Night flying would now start, but a lack of workshops, sleeping accommodation and fitters meant that not all aircraft could be kept serviceable at this time. By the end of April, training flights had reached their peak, and 157 was now ready for war.

On April 27th 1942, operations would begin. Three patrols would take off followed by four the next day and then three on the 29th. No visuals were recorded from the first two nights but a Do. 217 was identified but subsequently lost in cloud.

At the end of the month F/Lt. Stoneman (Engineer Officer) invented a modification that improved the effectiveness of the Browning’s flash eliminator, an improvement that was so successful, it was quickly adopted by the Air Ministry for other models.

Successes were slow coming to 157 Sqn, problems with the A.I. sets led to frustrations and missed opportunities, but eventually they did come, and the Mosquito proved itself to be a truly outstanding night fighter.

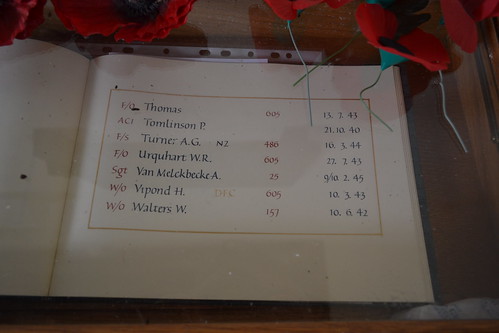

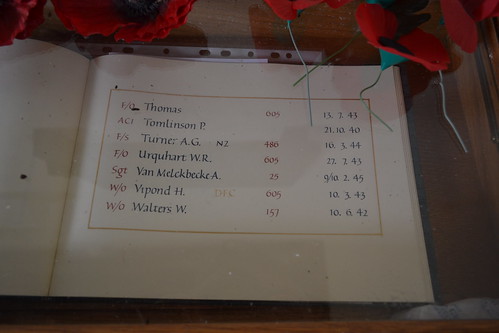

The Roll of Honour in All Saints Church lists W/O. W. A. C. Walters death as 10th June 1942. Walters (s/n 755538) arrived at Castle Camps on 22nd December 1941 (see above entry in O.R.B), he is currently buried in Nottingham Southern Cemetery, Sec. F.24. Grave 55. He was Son of Arthur and Annie Walters, of West Bridgford, Nottingham, and died at the age of 21.

By March 1943 a change in command, Wing Commander V. J. Wheeler, M.C., D.F.C. replacing W/Cdr Slade, and then as night defenders turned to intruders, the role of 157 Sqn changed, and they prepared to move to pastures new and R.A.F. Bradwell Bay.

Around this time a small detachment of Mosquitos would share the facilities at Castle Camps, 456 sqn, who were primarily based at Middle Wallop, would have aircraft use the site between March and August 1943 – a month that would take Castle Camps into a new period, and new leadership.

The 15th would be a very busy day for staff at Castle Camps, with the departure of 157 Sqn came the simultaneous arrival of 605 Squadron.

Part of the Perimeter Track that leads away to the airfield.

Led by the then Wing Commander George Lovell “Uncle” Denholm D.F.C., he was himself a Battle of Britain veteran, a Turbinlite advocate and was also famed for his part in the shooting down of the first German bomber on British soil. The famous ‘Humbie Heinkle’ was generally credited to Flight Lieutenant Archie McKellar of 602 Squadron from R.A.F. Drem, but Denholm and his 603 Sqn, played their part in damaging the aircraft before its eventual crash in East Lothian.

With the arrival of 605 Sqn and their Mosquitos, Castle Camps, like the stations at Bradwell Bay and Hunsdon, were quickly becoming synonymous with squadrons of the new type. Also Flying Mosquito IIs, (replaced four months later by the FB.VI) they would eventually depart here also for Bradwell Bay, but not before the ruggedness and reliability of the Mosquito would be put to the test.

On August 17th 1943, Sqn. Ldr. Mack and Flt. Sgt. Harrison, flew Mosquito FB.VI (HJ781) on a night intruder mission to Jagel in the northern most tip of Germany. Whilst on this mission, the aircraft was hit by a cable rocket projectile (Parachute and Cable or P.A.C.) fried from the ground. With a thin cable attached to a parachute they were designed to bring down allied aircraft and could be fired from either multiple or single launchers. HJ781, flew into one such cable which severed around 3 feet off the end of the starboard wing. The Mosquito, suffering considerable damage, managed to return to Castle Camps and was later repaired and returned to flight – such was the strength of the design of the Mosquito.

For the duration of their stay, 605 Sqn would perform almost nightly patrols over the airfields of the low countries and northern Germany, a tit-for-tat game played between the R.A.F. and the Luftwaffe, each aiming to catch returning aircraft as they approached their home airfield. A game that resulted in minor and relatively insignificant attacks on Castle Camps itself.

For eight months from June 1943, Castle Camps would be shared with a new squadron, the only squadron to be formed here, 527 Squadron, who were formed through the combining of both 74 and 75 Wing Calibration Flights from Duxford and Biggin Hill respectively. Flying a collection of Hurricanes (I & IIB), Blenheim IV and Hornet Moths, they would test the accuracy of Britain’s defence radar systems across southern England and East Anglia.

The October departure of 605 sqn left 527 the only unit operating from Castle Camps, and operationally all was quiet once more. In the December 1943, 410 Sqn, another Hunsdon Mosquito unit arrived, stayed for a short while and then returned to Hunsdon in the April of 1944. A short but active spell saw them victors over a number of German types.

1944 would see another flurry of activity, with units arriving and departing in quick succession, and it would be a few months before another Mosquito would grace the skies over Castle Camps once more. 486 Sqn (RNZAF) , yo-yoed between Castle Camps and Ayr during the month of March, bringing with them yet another potent and deadly weapons platform, the Tempest V; followed by 91 Sqn while they were upgrading their Spitfire XII to XIVs.

Giving a useful indicator of scale, F/O. J. R. Cullen of No. 486 Squadron (RNZAF), poses with his Tempest Mk V at Castle Camps. Cullen became a successful Operation DIVER pilot, shooting down around 16 flying bombs. © IWM (CH 13967)

Between March and June little happened at Castle Camps, 68 Sqn*4 breaking the quiet with their Beaufighter VIFs at the end of June, which were quickly replaced with Mosquito XVIIs and Mosquito XIXs. 68 (Night Fighter) Squadron was primarily an R.A.F. Squadron, but Czechoslovak pilots formed one of its flights. The determination of the Flight’s crews resulted in some high ‘kill’ rates, with twenty-one verified kills, three probable, seven enemy planes damaged and three V-1 flying bombs to their credit. The flight saw Twenty-three Czechoslovak pilots (twenty-one Czechs and two Slovaks) pass through their doors, culminating in an incredible 1,905 combat sorties covering 4,095 operational hours during the war.*5 By the October 68 Sqn too had departed, replaced by 151 Sqn and 25 Sqn for a short period both with yet another Mosquito model, the MK XXX.

1945 and the close of war saw units slowly begin to disband and wind down, 307 were followed by 85 Sqn who returned in the June and September also with the MK. XXX. A huge improvement and development from their early Hurricanes of 1939 / 40 and a fitting end to a station that had seen many a brave young man come and go. 25 Sqn also returned, in both the August and October with the Mosquito VI, staying until June 1946, whereupon the airfield closed and returned to agriculture, a state it remains in today.

Castle Camps has little – aviation wise – to offer the visitor these days. A recently erected memorial stands at the northern end of the airfield, the only visible marker of this once busy site that grew from a cold and windy field with little more than tents for accommodation, to a bustling site with possibly the most advanced and formidable fighters of the Second World War.

It may not appear to be much more than green fields and cattle farming, but sitting in the summer sun, as I did, you can still hear the rumblings of that magnificent engine the Merlin, as the Hurricanes and Mosquitos of the R.A.F. fly over your head transporting you back to those days of 1940s England.

Sources and further reading.

*1 The Castle Camps Village webiste details the history of the Castle.

*2 AIR/27/703/14 National Archives

*3 AIR/27/1045 National Archives

*4 An interesting blog highlighting some of the Czech pilots who flew with 68 Sqn.

*5 Pilot Josef Capka, D.F.M. (a member of the Guinea Pig Club) joined 68 Sqn after they left Castle Camps. His incredible story is told in the Free Czechoslovak Air Force blog and through his book ‘Red Sky at Night‘.

![Airmen of the 4th Fighter Group ride in the back of a jeep at Debden air base. A P-47 Thunderbolt is in the background of the shot. Passed by the U.S. Army on 2 October 1943, THUNDERBOLT MISSION. Associated Press photo shows:- Pilots at a U.S. Eighth Air Force station in England are taken by truck from the Dispersal room to their waiting P-47's (Thunderbolts) at the start of a sortie over enemy territory. L-R: Lt. Burt Wyman, Englewood, N.J. ; Lt. Leighton Read, Hillsboro, W.V.; F/O Glen Fiedler, Frederickburg, Tex. AKP/LFS 261022 . 41043bi.' [ caption].' Passed for publication ....1943'. [stamp].](https://i0.wp.com/www.americanairmuseum.com/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/freeman/media-377283.jpg)