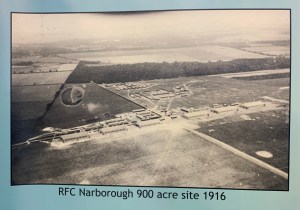

In Part 1, we saw how Narborough was established as a Night Landing Ground, and how the RNAS passed it onto the RFC to train pilots in aerial combat at great rick. In Part 2, that rick continues and so does the development of the aerodrome to the point it becomes the largest aircraft based airfield in Norfolk.

These departures left only the reserve squadrons at Narborough, and it wouldn’t be long before they too suffered causalities. The first of these to lose a valuable pilot was 50 Reserve Squadron on March 30th 1917. A young Canadian, not yet out of his teens, 2nd Lt. Allen Ingham Murphy, was killed when his Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 ‘A2720’ stalled whilst turning after take off. 2nd Lt. Murphy was the first of many casualties from the units that year – training young pilots was not getting any easier.

April saw the arrival of yet another of the Reserve Squadrons, with 64 Reserve Squadron (RS) being posted in from Dover (Swingate Down) in mid April. Another of the training units they would also bring RE8s, Avro 504s Nieuport 17s, BE2s and Shorthorns.

A second tragic accident on June 8th 1917, showed how fragile these aircraft could be. Lieutenant Hubert John Game was attempting a loop when he got into difficulty and ended up in a steep dive. Trying to pull the aircraft – a BE2 (A2794) – out of the dive was too much for its fragile structure and it suffered a catastrophic wing failure, both wing extensions breaking away leaving the aircraft uncontrollable. Lt. Game was originally a Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) and was attached to 53 (Training) Sqn RFC at Narborough, when he was tragically killed. He was also the younger brother of Air Vice-Marshal Sir Philip Woolcott Game, and was just 26 years old at the time of his death. He is another one of those whose grave lays a short distance away from the site of Narborough airfield.

Many of those who joined up to fight had jobs or were celebrities in their own field. Many famous actors went on in the second World War to have successful military careers, and many sports personalities also performed admirably. At Narborough, 2nd Lt. William Smeeth was a 22 year old who transferred into the RFC from the 9th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles. Before the war he attended the Loretto School (a prestigious boarding school whose building dates back to the 14th Century, and was founded in 1827 thus claiming to be Scotland’s oldest) from 1909 to 1913, and was a player in the Loretto XI. Considered a “fine, slow, left-handed bowler”, he was wounded in France and posted to Narborough as a flying instructor. On 17th July 1917 he was flying an Avro 504B (A9975) which was struck, whilst landing, by an A.W. FK8 which was taking off at the same time. In the accident Smeeth was killed, and he remains the only military grave in his home town of Bolton Abbey in the Yorkshire Dales.*6, 7

The inherent danger faced by trainees was made no more obvious once again on October 29th, when two more aircraft, both from 50 RS, were lost in separate accidents. The first an Armstrong Whitworth FK.8 (A2730) side slipped during a turn and nose dived into the ground killing both crewmen, 2Lt. Norman Victor Spear (aged 29) and Air. Mech. 1 Sidney Walter Burrell (age 22). The second aircraft, also an Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 (B219) spun off a low climbing turn also killing its pilot 2Lt. Laurence Edward Stuart Vaile (aged 23). It was indeed a black day for 50 RS and a stark reminder to the trainees.

In October and December 1917 two more units bolstered the numbers of personnel at Narborough. Firstly, 1 Training Squadron was reformed here on October 1st, whilst 83 Sqn, born out of 18 (Reserve) Squadron (RS), arrived at Narborough two months later, both these bringing a range of aircraft that they quickly swapped for FE.2bs. 83 RS had previously been based at Wyton commanded by Major V. E. Albrecht and were one of the first units designated a Training Squadron Station rather than Training Depot Station.

83 Squadron had only been formed in January that year and within three months of their arrival here, would be on the front line at St. Omer attacking enemy troop concentrations, attempting to stem the early German spring offensive.

The occurrences of all these tragic accidents was becoming so frequent, that one instructor, Capt. W.E. Johns, creator of ‘Biggles‘, later cited spies as the cause of many ‘accidents’ – claiming that they had tampered with the machines causing the deaths of the crews on board. Johns, himself having written off many machines, believed Americans with German sounding names were to blame for aircraft breaking up in mid-air or crashing at the bottom of loops. More likely however, the fault lay with over exuberant or simply poorly trained recruits.

Like most airfields, there were those locals who disliked the presence of the military and their new flying machines on their doorstep, and there were those who welcomed them into their villages and homes with open arms. Narborough was no different and there are many tales of interactions between military personnel and the local civilians.

The nearby Narborough Hall opened its doors to wounded brought in the from the fields of Flanders, whilst local people, in conjunction with airfield staff, held money raising events to help with food shortages. The local hostelries were frequented by personnel from the airfield, and friendly sports events were held between civilian and military teams. On some days, flying events were put on to display the aircraft and the skills of the pilots training with the RFC. Many came to watch in awe whilst others complained about low-level flying disturbing livestock, and pilots making a nuisance of themselves in the villages; others complained about the speeding lorries that brought in both supplies and men.

In early 1918 a year after the United States declared war, airmen of the 20th, 24th and 163rd U.S. Aero Squadrons were brought into Narborough and attached to 121 Sqn which had just formed in the opening days of the year. Whilst using a variety of aircraft, the backbone of the squadron was the DH 9, an aircraft they used until their departure to Filton in August and eventual disbandment.

As a unit set up to train the Americans, times were hard and often relationships were strained, the cold British winter weather being a substantial change from the hot climate of Texas from where many originated. These units, once here, were spread far and wide, amongst other squadrons across the UK; their Campaign Hat, a broad-brimmed, high-crowned hat, becoming synonymous with their presence.

There would be no let up in the movements in and out of Narborough. 1918 would see yet more arrivals in February with 26 Training Squadron (TS) and 69 Training Squadron (TS) both units being posted in during that month. Flying a mix of Henry Farman models, the two units would leave Narborough in August to form 22 Training Depot Station in Gormanston, Ireland. Whilst here in Norfolk though, they would carry out training duties, honing their skills alongside the already present training units and the newly arrived Americans.

As time passed, the angst between the US and RFC staff began to mellow. The initial feeling of US personnel having a much more ‘laid back’ approach to rank and uniform being extremely distasteful to the more rigid RFC officials. By the time they were to leave though, relationships had matured and their sad departure ended what had become a generally happy association between them all.

The last months of the war saw no let up in training either; keen to join the RFC young men continued to join up and train to fly. In mid February 1918, two 18 year old boys were perhaps fulfilling a dream when it all went tragically wrong. Flying a DH.4 (B2121), 2Lt. John Fyffe Shaw and 2Lt. Charles Arkley Law of 26 Training Squadron, were both killed after their aircraft’s engine failed causing it to stall and then nose dive with dire consequences into the ground.

When crews arrived at the scene the throttle was found only half open, suggesting the aircraft had stalled during the low level right-hand turn they were performing. Insufficient fuel would have starved the engine leading to it cutting out and causing the resultant crash. Both airmen were from Scotland, Shaw from Dundee where he remains, and Law was from Edinburgh – he remains buried in Narborough.

In a major reforming of the military structure on April 1st 1918, the RFC and RNAS were finally amalgamated officially forming the Royal Air Force, a major turning point in the history of the force as it is today. To reflect this, RFC Narborough also took on the new name RAF Narborough, but a mere name change wouldn’t stop the intense work from going on as usual.

As the summer approached and the weather improved, so too did the relationship between the various nationalities. The American’s arrival at Narborough was now matched by the arrival of some thirty or more women of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC)*2 – which along with the Women’s Naval branch (WRNS) and Women’s Legion, formed the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) on April 1st. Many of these women performed roles in admin sections of the Air Force, telephonists, catering and personal duties whilst some entered the more technical roles, parachute packing, riggers, mechanics and carpenters. By the war’s end, Narborough would have in excess of 100 female personnel working at its site.

On September 12th 1918, 55 Training Depot Station – who originally formed at Manston when 203 Training Depot Station (TDS) was renumbered – arrived here also to carry out training duties. A large number of these training Depots existed at that time and continued on to the war’s end. Like other training units 55 TDS also flew a large range of aircraft types; B.E.2e, D.H.4, 6, and 9, Avro 504j and k and S.E.5a.

This latest squadron to join the many arrived during a time of major redevelopment not only of the site, but the training units as well. Narborough with such a huge influx of staff was now developing new accommodation buildings, hangars and work space. Electricity supplies were at last being installed, new roads created to get men and supplies around the site much quicker and a new hangar, The ‘Red hangar’ – due to its red brick construction – was added near to Battles Farm. The site had become so big now that it was one of just a few considered for homing the new enormous Handley Page Bomber the V/1500 which was capable of bombing Berlin. But like both Sedgeford and Pulham that decision went elsewhere, to Bircham Newton, with its more suitable and stable soils and long term development potential.

Whilst no V/1500 was ever stationed at Narborough, Capt. J. Sinclair of 166 Sqn Bircham Newton, did land one on the site proving that it could be done and that Narborough airfield was more than able to cater for its needs. However, the aircraft never made the flight to Berlin, the Armistice being called just before the operation was planned to go ahead.

In November 1918, the war finally ended. After 4 and half years of brutal warfare, millions had died, a small fraction of those killed had been either based at, or passed through, RAF Narborough in their training.

Then, after the news of the cessation of conflict, the big reduction in manpower and machines would begin. As units began to arrive home from France they were quickly disbanded. At Narborough, several of these arrived as cadres, No. 64 (14th February), No. 56 (15th February)and No. 60 (20th February) where upon they joined 55 Training Depot Station to see out their last few months of existence.

Despite this, training continued on, but with less urgency than before. The arrival of one (Sir) Alan Cobham went rather unnoticed, just another instructor to train those stationed here. His focus was on those who struggled to achieve the status of ‘pilot’ for whatever reason – whether it be lack of ability or just through lack of ambition. He remained at Narborough until February 1919 at which point, like so many others, he was demobbed and returned to civvy street.

With flying restrictions now lifted, Cobham teamed up with brothers Fred and Jack Holmes forming their own Aviation Tours company buying an ex RAF Avro 504K, a car and some petrol. He soon added to this a second 504K (G-EAKX and G-EASF) with which they created the famous ‘Cobham’s Flying Circus‘, performing daring barnstorming shows across the country.

In 1921, with the great depression, he began to work for an aerial photographic company and air taxi firm, this led him on to long distance travel, becoming known as “the King of the Taxi Pilots“.*8

Cobham went on to have an incredible aviation life, pioneering both long distance flight and aircraft technology. He made civil aviation more accessible and popular to the masses his influence on aviation going far beyond the training of RAF pilots.

With the war over it was now time for harsh decisions. The monetary and human cost of the war had been astronomical and the military were now no longer the favour of the Government. A new restructure and decommissioning of vast quantities of military equipment was on the horizon. In one small gesture in March 1919, 55 Training Depot Station were disbanded only to be renamed 55 Training Squadron, this simple move brought it inline with other training units of the same designation.

The four units who arrived at the end of 1918, would now one-by-one disband or move on elsewhere to disband; 56 departing to Bircham Newton on December 30th where it disbanded a month later; 60 followed in January only to disband before the month was out, and 64 ended its days on New Years Eve 1919 at Narborough. With that, its days now over, Narborough was deemed surplus to requirements and with the disbandment of the recently renamed 55 Training Squadron, on New Years Eve, the airfield was unceremoniously closed for good.

The post war years saw the closure of many other war time airfields like Narborough. But unlike its sister station RAF Marham a mile or so away, it would remain closed. For over a year the site remained unoccupied and unused, and the usual vandalism began to take its toll. Machinery, tools and even scraped aircraft remained on site for enthusiastic youths to make their playground. Then in 1921, the buildings and contents were all sold off in a two day event over 2nd and 3rd February, in what was considered to be one of the biggest auctions in Norfolk: some of the items going to local farmers, other for small industrial units, some to schools and the like; Narborough was now scattered to the four corners of the county. The remainder of the site was sold to the farmer and it quickly returned to agriculture, a state it remains in today.

Some of the original buildings are reputed to have existed for many years, even to the present today, (a car show room in Cromer, a furniture warehouse in Terrington-St-Clement and a nearby hut at Setch) whether they still do, is difficult to ascertain, but most have long since succumbed to age, their inevitable deterioration and eventual demolition. In 1977 the last hangar on the airfield, a hangar known as the ‘Black Hangar’ was demolished after severe gales took the last sections of roof. With little option but to pull it down, it was removed leaving little trace.*2 The last full building on site, known as the ‘Racket House’ after personnel used it to play squash, burnt down in 1995, and with that the last trace of the airfield was wiped away.

Narborough itself having no hard runways or perimeter tracks has long since gone. A small memorial has been erected by the Airfield Research Group who are part of the Narborough Local history Society, aiming to promote and preserve the memory of RFC/RAF Narborough; a memorial plaque also marks the graves of those who never made it to France, and the small Narborough Museum & Heritage Centre holds exhibits of 59 Squadron in the local church.

During the First World War some nineteen Victoria Crosses were awarded to members of the RFC/RAF, of those three had passed through Narborough. Several famous individuals also cut their teeth at Narborough, and some went on to achieve great things in the aviation world. Many trainees lost their lives here, but many became successful pilots seeing the war out alive.

Significant not only in size, but in its history, Narborough has now been relegated to the history books. But with the dedication and determination of a few people the importance and historical significance of this site will hopefully continue to influence not only the aviators of tomorrow, but also the public of today.

After Narborough, we head east once more toward Swaffham. After turning off the main A47 we come across another American airfield. In the next part of this trip we visit the former RAF Attlebridge.

The full story of Narborough can be read in Trail 7 – North West Norfolk.

Sources and further reading (RAF Narborough)

National Archives: AIR 27/554/1; AIR 27/558;

*1 Fleet Air Arm Officers Association Website accessed 14/6/21

*2 Narborough Airfield Research Group “The Great Government Aerodrome” NARG, 2000

*3 RAF Museum Story Vault Website accessed 14/6/21

*4 Letter from 2/AM C. V. Williams from 59squadronraf.org.uk

*5 On May 31st 1917, all RFC ‘Reserve Squadrons’ were renamed ‘Training Squadrons’.

*6 “Loretto Roll of Honour 1914-1920” National Library of Scotland digitised copy. accessed 17/5/25 via Google books.

*7 Renshaw, A., “Wisden on the Great War – The Lives of Cricket’s Fallen 1914 – 1918“. Bloomsbury. 2014

*8 Gunn. P., “Flying Lives with a Norfolk Theme“. Gunn. 2010

The book “The Great Government Aerodrome” is an excellent publication about the history of Narborough and contains a great many photos and personal stories of those who knew Narborough. It is well worth a read.