On the windswept Fens bordering Lincolnshire and Norfolk lies a site that shaped the skies of World War II. Far more than a quiet airfield, it was a crucible for pilots from Britain, the Commonwealth, and beyond, where Hurricanes, Spitfires, and Wellingtons soared – and often fell – as young airmen learned the deadly art of aerial warfare.

From rocket-firing trials to emergency landings, from multinational trainees to seasoned instructors, this airfield was a hub of innovation, skill, and courage. Lives were lost, lessons were learned, and generations of aircrew left ready to defend Britain’s skies. Though the airfield has largely returned to nature, its legacy remains – a testament to bravery, determination, and the high stakes of war in the air.

In Trail 3, we revisit the airfield that was RAF Sutton Bridge.

RAF Sutton Bridge

The origins of Sutton Bridge airfield are rooted some 20 years before the start of the Second World War, and largely owes its creation to the Holbeach firing range located in the shallows of the Wash just a stones throw north of the airfield. The range, which is still in operation today, was first supported by the airfield at Sutton Bridge as early as 1926 – a basic airfield from which to base those units using the range.

From Fens to Flying Fields

The airfield itself sits on the edge of the Fens, a flat, open area often referred to as ‘desolate’ and ‘drab’. In winter, certainly the wide open expanses allow winds to blow freely across its dark silt substrate, much of which lay under water for millions of years previously. But this dark open landscape offers prime agricultural and historical prospects, the Romans, Vikings and the Icini people all having made their mark on its dramatic landscape.

The airfield’s roots go back as far as the end of the First World War, the then newly formed RAF was cut back hard, reduced to a mere twenty-five squadrons for both home defence and to protect the commonwealth’s interests abroad. With little need seen for a home based air force, little thought was put into preparing pilots and gunners for any likely future conflict. To keep pilots busy, aerobatics and formation flying took preference over mock dog fights, aerial warfare tactics and ground attack practise.

But by the 1920s, this was not seen as productive and thoughts began to turn to training crews more responsibly, after all, if a pilot cannot engage and defeat his enemy then what use is he? So, a new firing range was sought to train pilots and gunners in the art of ground attack and air-to-air firing. The area required for such a task would need to be away from the public, but easily accessible and coastal, preferably with shallows waters. In 1925, several areas were seen as possible candidates; Catfoss, Donna Nook and an area known as Holbeach Marsh on the Lincolnshire / Norfolk border. After inspection by the Air Ministry, all three were deemed ideal, and so they took control creating three new ranges for the RAF’s use.

To be able to access the range at Holbeach, a nearby airfield was then needed, and being the closest, the former World War 1 site at Tydd St. Mary was given first consideration. However, strong objections from both local landowners and the council jointly, persuaded the military otherwise, and so an alternative had to be found.

The Birth of Sutton Bridge

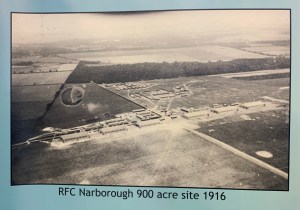

The Ministry looked further east, nearer to the Wash, and found a small area close to the village of Sutton Bridge on the Lincoln / Norfolk border, about a mile or so from the sea. It would be perfect, and so an area of some 130 acres was obtained through either purchase or lease, allowing, on 1st September 1926, the birth of the soon to be, RAF Sutton Bridge.

The airfield’s main entrance gate and guard house, leading down towards the Mechanical Transport (MT) Shed, Bessonneau hangars and the airfield ground beyond. Visible in the far left background is the new Hinaidi type aircraft hangar built during the 1930s replacing two of the airfield’s original four Bessonneau type aircraft hangars. (source wiki)

Sitting on prime agricultural land, the airfield was hemmed in by both the River Nene along the western boundary and a former LNER railway line (now the A17 road) along the northern boundary. The borders of the two counties, Lincolnshire and Norfolk, cross the airfield resulting in it being divided between the two. The nature of this design though, would later on, lead to many problems. The airfield being irregular in shape, meant that landing across it – cross-wind east / west – was very difficult if not impossible as there was insufficient room to do so. This would, in itself, restrict the number of days on which flying by trainees could take place, thus forcing them to make difficult cross-wind landings when they did.

In these early days Sutton Bridge would be rudimentary at best, bell tents being the main form of accommodation; only developing as new and longer training courses were needed. More permanent buildings were gradually erected including an Officers’ Mess, permanent accommodation blocks and maintenance workshops.

The 1920s was not a time for major airfield construction though, very few companies had developed or mastered the necessary skills needed for good airfield development. A local business, Messers Thomson and Sons of Peterborough, were initially brought in, commencing the construction with small roads and tracks, along with four canvas Bessonneau hangars for storage and maintenance. Rudimentary maybe, but it was beginning to take some shape.

Expansion and Identity: Sutton Bridge in the 1930s

The emergence of the ‘expansion period‘ in the 1930s, saw a period of rapid change and development in the military, where the need for airfields and a strong air force was seen as priority. Airfield development now began to improve and new companies, skilled in their design and construction, emerged onto the scene. One of these, “En-Tout-Cas”, in conjunction with other smaller companies, was enlisted to oversee the continued construction of the site at Sutton Bridge. These new and more experienced companies were employed under contract directly with the Air Ministry, using both civilian workers and their equipment, to build not only Sutton Bridge but Catfoss, Lee-on-Solent and Sealand as well *1

On January 1st 1932, the various training sites including Sutton Bridge were given formal titles – Armament Training Camps (ATC) – with each being given a number to distinguish them. Sutton Bridge became known as No. 3 ATC, handling fighter squadrons. Over the next few years it would go through a series of name changes, the first being on 1st April 1938, when it became 3 Armament Training Station (ATS), and then again, a year later, it would close only to reopen under the name of 4 Air Observers School (AOS).

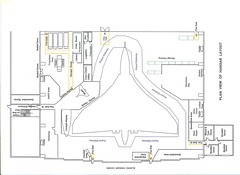

Being better skilled in airfield design and construction, specific buildings for particular tasks were now being added to the work already done, small blocks for administration, maintenance sheds and such like all began to spring up. Being a pre-war construction, all buildings, including accommodation blocks, were placed directly on the airfield site rather than being dispersed as was the norm later on. Dispersals for aircrew were located at different points around the airfield’s perimeter, alongside the aircraft dispersals, and were brick built to protect crews from the heat and cold of the Fen weather.

The early Bell tents and Marquees were gradually replaced with more permanent brick structures arranged neatly in rows alongside the access road. Even with more permanent structures to bed down in, the comforts of a proper bed failed to materialise, instead metal stretchers with sawdust filled wadding for a mattress became the norm. *2

Wartime Growth and Shifting Commands

The runways of which there were three, were initially grass, but as the war progressed these were upgraded to ‘hard’ surfaces using a mix of steel matting, 080 American Planking and 130 Sommerfeld Track; all variants of metal planks that locked together to form a temporary but hard base. A concrete perimeter track was installed and fourteen hardstands were added using a hardcore base with tarmac coverings. In addition, two Bellman hangars, one Aeroplane Repair Section (ARS) Hangar and twelve 69 ft blister hangars were also erected on site. By the time it was established it had become a formidable site.

Sutton Bridge was passed directly to RAF control fourteen days after initial construction began, followed two weeks later by the arrival of the first RAF personnel from RAF Bircham Newton.

In these pre and early war years, the airfield would go through a series of ‘owners’ with 25 (Armament Training Group) under The Flying Training Command taking over in 1937 followed by 12 Group Fighter Command in September 1939 and finally back to The Flying Training Command once again in April 1942. The rapid change of ownership reflecting the many changes that the airfield would go through and the many units that would use its meagre but highly regarded facilities.

All these changes would mean that personnel numbers would fluctuate throughout the war depending upon who was there and what courses were being run, but in general the airfield accommodation could initially cater for 109 Officers, 110 Senior Non-Commissioned Officers and 110 ordinary rank male personnel; WAAFs were also catered for with 6, 12 and 361 respectfully. The fluctuation in staff would also reflect the numbers and types of aircraft on site. It is known that at one point there were no less than ninety Hurricanes plus other trainers along with Spitfires and Wellingtons on the airfield at one time.

For those travelling here on a posting, a train station was conveniently placed across the road from the airfield, getting to and from it was therefore relatively easy as long as the trains were running.

Photograph of the airfield’s main entrance (left) the Mechanical Transport (MT) Shed and on-site airfield road leading down towards four Bessonneau hangars and the airfield ground beyond. (Source via Wiki)

So far we have seen how Sutton Bridge began, how its origins owe its thanks to the range at Holbeach and how over the immediate post war years it developed as an airfield. In Part 2, we progress through the 1920s and 1930s towards war, during which time, Sutton Bridge shone in the public eye, with pageants and air displays that enthralled the locals.

The full story can be read in Trail 3 – Gone but not Forgotten.