There are multiple stories of heroism and daring stemming from the Second World War, each and everyone pushing man and machine beyond their boundaries. Many daring missions were flown in which crews performed and completed their task with extraordinary bravery and at great cost to both themselves, and to those on the ground.

Stories such as the ‘Dambusters’ have become famous and commemorated year on year, and yet another daring raid is barely mentioned or even considered by those outside of aviation history. The details of the raid remained secret for years after the event and even now, factual evidence is scarce or difficult to find; even the name of the operation can cause heated debate. The merits of the operation continue to be debated and many are still divided as to what the true purpose of the operation really was.

Whatever the reason behind it however, the historical fact is that the operation was a daring, low-level raid that helped many prisoners of war escape captivity and probably death, and one that was carried out in very difficult circumstances by a group of extremely brave young men.

It was of course the raid on the Amiens prison on February 18th 1944, by nineteen Mosquitoes of 140 Wing based at RAF Hunsdon.

As a new wing, it was formed at RAF Sculthorpe, and would consist of three multinational squadrons, a ‘British’, Australian and New Zealand unit, and all would be based at Hunsdon as part of the RAF’s Second Tactical Air Force (2TAF) designed to support ground troops in the forthcoming invasion of Europe.

Group Captain P C “Pick” Pickard (centre), Commander No. 140 Wing, flanked by Wing Commander I G E “Daddy” Dale, Commanding Officer of No. 21 Squadron RAF (to Pickard’s right), and Wing Commander A G “Willie” Wilson, Commanding Officer of No. 487 Squadron RNZAF, visit No. 464 Squadron RAAF at Hunsdon, prior to a daylight raid against flying-bomb sites in the Pas-de-Calais. 464’s Mosquitoes (FB Mk VIs) have been loaded with 250-lb MC bombs for the operation: HX913 ‘SB-N’ can be seen in the background (@IWM HU 81335).

The raid on Amiens was not the only low level raid carried out by the Wing however. Between 1944 and 1945, they would attack numerous ‘V’ weapons sites, along with the Gestapo headquarters at Aarhus University and the Shellhaus building in Copenhagen. Operation Carthage, another of their more famous raids, occurred whilst the wing was based at RAF Fersfield in 1945, but their most controversial raid, Ramrod 564 or ‘Operation Jericho’ as it has since become known, took place the year prior to that, whilst they were based at Hunsdon in early 1944.

There is a lot of speculation around Ramrod 564, many of the official records are missing, inaccurate or even vague. The operational record books for the squadrons involved are recorded as ‘secret‘ and contain no details other than aircraft, times and dates.

The Operation, was designed to assist in the escape of 120 French patriots, who were reportedly condemned to death for assisting the Allies in the fight against the Nazis. These prisoners included key resistance fighters who had considerable knowledge of resistance operations in France, and so it was imperative that they escape.

The plan was for Mosquitoes of 140 Wing to attack from different directions, breaching the walls of the prison and blowing up several key buildings inside the prison holding German guards and soldiers. It would require each aircraft to carry 11 second, time-delay fuses in 500lb bombs dropped at very low level.

The Operation, formulated by Air Vice Marshal Basil Embry, would be critical, even the amount of explosive itself had fine limits, and time was also of the essence. The prisoner’s executions were imminent, so the attack had to be carried out quickly thus allowing only a small window of opportunity for the operation to take place.

The exact time of day that the attack could take place was also critical, there needed to be as many of the guards as possible in the key buildings at the time of attack, and the prisoners needed to be safely gathered together out of harms way. So, a time of 12:00 pm precisely on a date between 10th and 19th February was chosen, as both the guards and prisoners would be having lunch at this time, and it would be prior to the executions being carried out.

The route would take the aircraft from Hunsdon to Littlehampton, then via appropriate lattice to Tocqueville / Senarpont / Bourdon – one mile south, Doullens / Bouzincourt – two miles west-south-west, Albert / target – turn right – St. Saveur / Senarpont / Tocqueville / Hastings and return to Hunsdon.

In the attack, 3 waves of Mosquito would be used, 6 from 487 (RNZAF) Squadron, 6 from 464 (RAAF) Squadron and 6 from 21 Squadron. In addition, to record the attack, one aircraft (a Mosquito) of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) was detailed to monitor and film the entire operation. Along with them were three squadrons of Typhoons (198, 174 and 245) each protecting one of the three waves. These escorts were ordered to rendezvous with the waves one mile east of Littlehampton at Zero minus 45, 42 and 32 minutes respectively.

The first wave of Mosquitoes was directed to breach the wall in at least two places, the leading three aircraft attacking the eastern wall using the main road as a lead in. The second section of three aircraft would, when ten miles out from target, break away to the right at sufficient height as to allow them to observe the leading three aircraft, and if successful, attack the northern wall on a north-south run, immediately following the explosion of the bombs of the leading section. The time of this attack Zero Hour.

The second wave was ordered to bomb the main prison buildings, the leading three aircraft attacking the south-eastern end of main building and second section of three aircraft, attacking the north-western end of the key building. Both attacks were to be carried out in a similar fashion to the first. This would follow three minutes behind the first wave at Zero +3.

The final wave was a reserve wave intended to bomb if any of the first two waves failed to hit their targets. They would follow the same patterns as the first two, one section from east and one from north, but they would only bomb if it was seen that one of the previous attacks had failed. The details of the attacks would be determined by the leader and would happen thirteen minutes (zero +13) after the initial planned attack. If they were not required, the order to return would be given by the Group Leader or substitute.

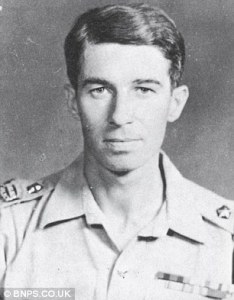

Embry elected himself to lead the attack, but this was blocked by those higher up, As a result, and much against his wishes, Embry therefore had to choose a successor. Group Captain Percy C. Pickard (D.S.O. and two bars, D.F.C.) was chosen, but even though he was known as an expert pilot and leader, Embry was not convinced of Pickard’s ability to complete the job at such low level. Despite his reservations though, Embry duly informed Pickard of the decision and preparations for the operation began in earnest.

On February 18th that year, a day after the initial planned attack and in extremely poor weather, the Nineteen Mosquitoes took off to attack, breech and destroy the walls and a key building of the Amiens prison.

During the flight out, two Mosquitoes and three Typhoons of 198 Sqn became lost in swirling snow and were forced to turn back as they had now lost contact with their main formations. The remaining crews flew on, but whilst over France a third Mosquito, flown by Flt. B. Hanafin, suffered engine problems and was also forced to turn back. On his return journey he was attacked by Flak from which he was seriously injured. Helped by his navigator the two were able to land back at RAF Ford where he was given medical treatment for his injuries.

Just three minutes behind schedule, the first wave split and the first three aircraft followed the main road toward the prison’s eastern wall at tree top height. The second set of three waited and observed. Wing. Cdr. I. Smith, 487 Sqn, went in first, dropping his bombs with 11 second fuses against the wall. The second three then followed as instructed.

Official reports state (edited only for fluency):

“Three Mosquitoes of No 487 Squadron attacked the eastern wall at 12:03 hours, just clearing the wall on a heading of 250 degrees with 12 bombs. The leader’s bombs were seen to hit the wall five feet from the ground, while other bursts were seen adjacent to the west wall with overshoots in fields to the north. Two aircraft of no 487 Squadron attacked the northern wall at 12:03 hours just clearing the wall on a heading of 150 degrees with 12 bombs. These attacks were directed at places later reported breached by reconnaissance aircraft. One bomb seen to hit the large building, and northern side of the eastern building was also reported hit.”

The second wave then attacked the south-eastern main building and north-western end respectively. Following the explosions chaos ensued inside the prison, guards were taken by surprise and over running bombs had caused some damage inside, prisoners began to run toward the gaps but some had been injured or struggled to escape.

The 12 foot wide breach in the south side of the prison’s outer wall, through which 258 prisoners escaped. © IWM (C 4740)

Again reports say:

“Overhead view of the prison, showing the breaches made in the outer walls. Two Mosquitoes of No 464 Squadron bombed the eastern wall at 12:06 hours from 50 feet heading 150 degrees and 250 degrees with 8 x 500lb bombs. The wall appeared unbreached before the attack. Results were unobserved.

Two Mosquitoes of No 464 Squadron bombed the main building at 12:06 hours from 100 feet heading 150 and 250 degrees with 8 x 500lb bombs. The north wall appeared to be already damaged. One of these aircraft was seen to bomb and has not returned.

The breach in the Eastern wall. One Mosquito of the PRU circled the target three times between 12:03 and 12:10 hours from 400 to 500 feet using a cine film camera but carrying no bombs. He reported a large breach in the eastern centre of the north wall and considerable damage to the extension building west of main building as well as damage to the western end of main building. A number of men were seen in the courtyard near the separate building which appeared to be workshops and three men running into fields from large breach in northern wall.

The four aircraft of No 21 Squadron received VHF messages from ‘F’ of No 464 Squadron (Gp. Capt. Pickard) and PRU aircraft when between 2 and 4 miles from the target, instructing them not to bomb. Target was seen covered with smoke and they brought their bombs back.

The target was obscured by smoke, so later aircraft were instructed not to bomb. Two aircraft were missing from this operation; one was last seen circling the target and heard giving VHF messages not to bomb (Pickard) and the other after attacking the target, was seen at Freneuville at 12:10 hours at 50 feet leading his formation. It attacked a gun position and shortly afterwards dropped to starboard and was not seen again. One aircraft of No 467 Squadron was hit by light flak near Albert; starboard nacelle holed and starboard wheel collapsed on landing. One aircraft of No 21 Squadron landed at Ford – aircraft damaged. One aircraft of No 487 Squadron abandoned task south of Oisemont – pilot slightly wounded and aircraft damaged. Two aircraft of No 21 Squadron abandoned before leaving English Coast owing to technical failure.”

It is thought by some that Pickard had been shot down before giving the return order, but these reports state that it was both Pickard and the PRU Mosquito flown by Flt. Lt. Wickham, that gave 21 Sqn the “Red, Red, Red” order, sending the last wave home as their bombs were no longer needed.

After the attack, FW.190s began to swarm and various dogfights took place between them and the Typhoons, but not before they had attacked some of the fleeing Mosquitoes who also returned fire.

It was one of these FW190s flown by the ace Feldwebel Wilhelm Mayer, who severed Pickard’s tail sending the aircraft into the ground near to Saint Gratien killing both occupants.

A story goes that Pickard had left his dog ‘Ming’ at RAF Sculthorpe, their previous airfield, to be looked after whilst he was away. On the day he was shot down, 18th February 1944, the dog fell gravely ill. Pickard’s wife, Dorothy, went to get him and sensed that after seeing the state of the animal that Pickard had been killed . It took months for Ming to recover, and some years later whilst living in Rhodesia, Ming went outside looked up to the sky as he always did when Pickard was flying, heard a whistle, collapsed and died.*1

Group Captain P. C. “Pick” Pickard with his pet sheepdog “Ming”, pictured while resting from operations as Station Commander at Lissett, Yorkshire. © IWM (CH 10251)

A famously brave act, the attack resulted in the death of three crew members; Gp. Capt. Percy C. Pickard, and Flt. Lt. John A. Broadley, (RNZAF), both in Mosquito HX922, ‘EG-F’, and Flt. Lt. Richard W. Samson, (RNZAF) in Mosquito MM404 ‘SB-T’. Samson’s pilot, Sqn. Ldr. A. I. McRitchie survived his crash and was taken prisoner. Two Typhoons from 198 Sqn escorting the Mosquitoes are also thought to have failed to return (the ORBs don’t confirm this). Considered a success at the time, ‘evidence’ has since come to light to suggest that the operation was ‘unnecessary’, and may have failed to achieve anything more than a successful PR role (see end note). *2

Of the 700 prisoners detained within the walls of Amiens prison that day, a total of 258 escaped. In the confusion, 102 were killed and a further 74 wounded, but the success remained secret from the public for another eight months. With so much speculation around the attack, it will no doubt remain one of the mysteries of the war, but it was without doubt, an incredibly brave and daring mission that cost the lives of many superb young men.

A podcast using eyewitness accounts from the Imperial war museum can be heard through their website.

(A better quality version is available on the Pathe News website.)

All controversy aside, the raid took place at very low level and in very poor weather, with bombs dropped against a wall with delayed fuses. There was little resistance on the flight in and Typhoons provided higher cover when it was needed, but dogfights still ensued and lives were lost.

A daring attack, the Amiens raid was not the only one where lives were lost. Airfields along with the Hazmeyer electrical equipment factory at Hengels in Belgium, were also attacked at low level. On this particular operation Mosquito MM482 was hit by intense flak setting the starboard engine on fire. As a result, the aircraft flown by Canadian Sqn. Ldr. A. W. Sugden with navigator Fl. Off. A. Bridger, was lost and both men were listed as missing. Having been with the squadron since 1942 they were considered ‘old timers’ by the others and were sorely missed.

The three squadrons of 140 Wing would later depart Hunsdon, leaving the joy of success and the turmoil of a thousand questions behind them. 464 went first on March 25th whilst 21 and 487 Sqns would both leave mid April, both moving to RAF Gravesend in Kent.

The Amiens raid has no doubt caused great controversy, and as the years pass it will probably seep into the depths of history where it’ll become ‘just another raid’. But whist the background to it remains a mystery, it was done with great valour and courage by a group of young men who believed strongly that it was a worthy and much needed attack.

Aircraft involved in the attack (all Mosquito Mk.VI):

Crews attacking the target:

No 487 Squadron

‘R’ Wg Cdr Smith, DFC (Pilot) / Flt Lt Barnes, DFM (Navigator)

‘C’ Plt Off Powell / Plt Off Stevenson

‘H’ Flt Sgt Jennings / WO Nichols

‘J’ Plt Off Fowler / WO Wilkins

‘T’ Plt Off Sparkes / Plt Off Dunlop

No 464 Squadron

‘F’ Wg Cdr Iredale, DFC / Flt Lt McCaul, DFC

‘O’ Fg Off Monghan, DFM / Fg Off Dean, DFM

‘A’ Sqn Ldr Sugden / Fg Off Bridger

‘V’ Flt Lt McPhee, DFM / Flt Lt Atkins

Missing (Killed/POW)

No 464 Squadron

‘F’ Gp Capt P C Pickard, DSO, DFC / Flt Lt J A Broadley, DSO, DFC, DFM

‘T’ Sqn Ldr A I McRitchie / Flt Lt R W Samson

Crews instructed not to attack the target:

No 21 Squadron:

‘U’ Wg Cdr Dale / Fg Off Gabites

‘O’ Flt Lt Wheeler, DFC / Fg Off Redington

‘J’ Flt Lt Benn, DFC / Fg Off Roe

‘D’ Flt Lt Taylor, DFC / Sqn Ldr Livry DFC

Abortive Sorties

No 487 Squadron

‘Q’ Flt Lt Hanafin / Plt Off Redgrave

No 21 Squadron

‘P’ Flt Lt Hogan / Flt Sgt Crowfoot

‘F’ Flt Sgt Steadman / Plt Off Reynolds

PRU

‘C’ Flt Lt Wickam, DFC / Plt Off Howard

Escorts (Typhoons)

198 Squadron (six aircraft set off, three returned early)

174 Squadron (Eight aircraft took off and rendezvoused with Mosquitoes)

245 Squadron (Eight aircraft took off rendezvoused with Mosquitoes)

Sources and Further Reading

*1 Gunn, P.B., “Flying Lives – with a Norfolk Theme“, Peter Gunn, 2010

*2 – The Amiens raid is one that has become embedded in history and is beyond doubt an incredible and daring low-level raid that succeeded in its aim. However, official records seem to have many errors, anomalies or missing details that it is very difficult to ascertain the accuracy of these historical ‘facts’.

The ORBs for each of the four squadrons give no details other than an ‘operation to France’, some crew names and aircraft numbers. There is no record of the use of the word ‘Jericho‘ but there are two sides to this story.

Some authors including Rowland White “Mosquito” and John Laffin “Raiders – Great Exploits of the Second World War“, both cite Basil Embry as the creator of the name ‘Jericho‘ before the missions took place, whilst Robert Lyman “The Jail Busters” cites a French film, made in 1946, as the author of creator of the name. Some believe the name was created by various media outlets since then whilst others say that Embry created the name after the operation had been carried out. It is however, widely considered that it was a post-war name as the original operation was ‘Ramrod 564‘ and none of the ORBs use the name ‘Jericho‘. To further add mystery, the use of the title ‘Renovate‘ has also cited, but records in the National Archives show this as the secret VHF code word to be used by aircraft on the operation and not the Operation title.

The name aside, and more recently, one of the French Resistance fighters revealed his doubts about the operation, and considers that it may have been nothing more than a propaganda operation or a diversionary attack linked to D-Day. One book (one amongst many) on the subject has been written by author Simon Parry and historian Dr Jean-Pierre Ducellier entitled ‘The Amiens Raid – Secrets Revealed‘ and is published by Red Kite. It goes into the details of the raid and possible reasons behind it.

There have also been theories that it was an MI6 operation but due to the nature and secrecy of the mission, little evidence is publicly available to substantiate this.

Of those who lost their lives, both Pickard and Broadley are buried in St. Pierre Cemetery, Amiens, whilst Sampson is buried in the Poix-de-Picardie cemetery in the Somme region.

The Official report and details from it were accessed at the National Archives Web Archive © Crown Copyright 2004 and © Deltaweb International Ltd 2004

National Archives:

AIR-27-264-25; AIR-27-1170-23; AIR-27-1170-24; AIR-27-1924-27; AIR-27-1924-28; AIR-27-1935-27; AIR-27-1935-28; AIR-27-1109-4; AIR-27-1482-4; AIR-27-1482-3

Thirsk. I., “de Havilland Mosquito – An Illustrated History Vol 2“. Crecy. 2006

White. R., “Mosquito” Bantam, 2023.