The Royal Air Force was made up of many nationals including both those from the Commonwealth and those from across the globe.

In Bomber Command, and the Pathfinders in particular, one man stood out not just for his nationality, but for his bravery and dedication in the face of death.

That man was one Acting Major*1 Edwin Essery Swales VC, DFC based at RAF Little Staughton on the Bedfordshire / Cambridgeshire border.

Swales was born on 3rd July 1915, the son of Harry Evelyn Swales and Olive Essery, in Inanda, Natal South Africa. He was one of four children whose father was a farmer. Whilst Edwin was young, his father, Harry, died from the influenza epidemic that claimed some 50 million lives after the First World War. Without a father, the family were unable to maintain the farm, and so they moved away to Berea in Durban.

Once of high school age, the young Edwin Swales attended Durban High School, he also joined the Scouts learning valuable skills with like minded youngsters, that would help in him in later life. After leaving school Swales landed himself his first job, working at the international branch of Barclays Bank in Durban. But with with war looming, Swales like many young men at the time, was drawn to military service, and so he joined up, posted to the Natal Mounted Rifles where he achieved the rank of Sergeant Major.

Whilst with the Mounted Rifles, Swales served in several locations including: Kenya, Abyssinia and North Africa where he fought bravely alongside his compatriots and the Eighth Army under Montgomery. He would remain with the rifles until January 1942 at which point he transferred to the South African Air Force, obtaining his wings on 26th June a year later. Two months after this milestone, he, like many others from across the commonwealth, was seconded to the Royal Air Force ensuring his position overseas.

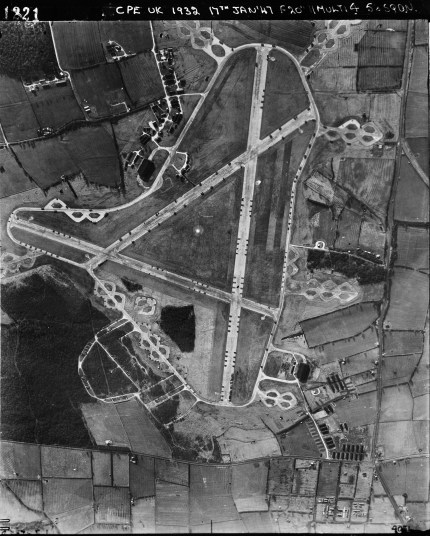

Swales (s/n: 6101V) like many new recruits to the Royal Air Force, would undergo a tense period of retraining, eventually being posted to fly heavy bombers within Donald Bennett’s 8 Group – ‘The Pathfinders’. His first and only posting, would be at Little Staughton with 582 Sqn.

During his short time at Little Staughton, Swales would fly a number of missions piloting Avro’s delight, the four engined heavy bomber the Lancaster.

Swales took part in many operations over occupied Europe, including the ill-fated attack on Cologne on December 23rd 1944, which saw the loss of five aircraft from 582 Sqn. In total, eight aircraft from seventeen flying from both Little Staughton and Graveley were lost that day including the lead bomber flown by Sqn. Ldr. Robert Palmer who himself was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions.

On that day, an Oboe mission that went terribly wrong, Swales heard the instruction to bomb visually releasing his bombs at 12:51hrs. Flak and fighter attacks were so ferocious, that Swales, like many others in the formation, had to take “violent evasive action” to shake off persistent and accurate attacks from fighter and ground based gunners. He was able to return his aircraft and crew safely to Little Staughton landing at 14:35*2

The action taken by Swales that day was indicative of his determination to succeed and protect both his aircraft and crew, and one that would be repeated time after time by the airman. As a result, it was seen fit to award Captain Swales the DFC for his action that night, his citation stating:

This Officer was pilot and Captain of an aircraft detailed to attack Cologne in December, 1944. When approaching the target, intense anti-aircraft fire was encountered. Despite this, a good bombing attack was executed. Soon afterwards the aircraft was attacked by five enemy aircraft. In the ensuing fights, Capt. Swales manoeuvred with great skill. As a result his gunners were able to bring effective fire to bear upon the attackers, one of which is believed to have been shot down. Throughout this spirited action Captain Swales displayed exceptional coolness and captaincy, setting a very fine example. This Officer has completed very many sorties during which he has attacked a variety of enemy targets*3

Within two months of the operation and at the time his award was being awarded, Swales would be in a similar position again. This time as Master Bomber leading the formation and directing the bombers to the target.

On that night, only ten days after the historical attack on Dresden, 367 Lancasters and 13 Mosquitoes from 1, 6 and 8 Groups were detailed to attack the city of Pforzheim to the north-west of Stuttgart. This would be the only attack on the city during the war and it would prove almost as devastating as both Dresden and Hamburg.

Flying along side Swales that night in his Lancaster III PB538 ‘N’, were seven other crewmen, including two navigators as was commonplace for Oboe fitted aircraft.

On the run in to the target, the Lancaster was badly mauled by night fighters who successfully put one engine and the rear turret guns out of action. But undeterred, Swales remained on station guiding the following bombers onto the target with the greatest of precision.

When he was finally satisfied that the attack had been carried out successfully, he left his station and turned the aircraft for home. It had been difficult to keep the Lancaster flying, but Swales had persevered in order to complete the job. But he was now easy prey for enemy fighters and inevitably more attacks came.

Soon a second engine was put out of action and flying controls were damaged further with some now completely inoperable. With a reduced speed and difficult flying conditions he headed for the allied lines, where he hoped to get his crew out safely.

All those on board made the jump to safety, leaving just Swales at the controls of the failing Lancaster. As if someone had been watching over them, just as the last man left, the Lancaster finally gave up the struggle and dived into the earth – Edwin Swales was still sat at the controls when it was found later on.

The attack on Pforzheim was considered to be very accurate, with over 1,800 bombs having been dropped in as little as twenty minutes or so. Over 17,000 people were known to have died that night in the raging fire that followed the bombing, and a post-war photo, revealed that 83% of the built up area had been destroyed by the raid *4

Following the death of Captain Swales, Air Chief Marshall Sir Arthur Harris KCB, OBE, AFC, Chief of Bomber Command, personally write to Swales’ mother saying: “On every occasion your son proved to be a fighter and a resolute captain of his crew. His devotion to duty and complete disregard for his own safety will remain an example and inspiration for all of us.”*10

For his action, bravery and dedication to duty, 29 year old Edwin Swales, a prominent rugby player and South African “who only had to smile at his crew and they were with him all the way“*5 was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously, the second such award to go to an airman of RAF Little Staughton, just one of three to the Pathfinders and one of only four South Africans to be awarded the Victoria Cross during the war. His citation appeared in the Fifth Supplement to The London Gazette, of Friday, the 20th of April, 1945:

Air Ministry, 24th April, 1945.

The KING has ‘been graciously pleased to confer the VICTORIA CROSS on the undermentioned officer in recognition of most conspicuous bravery:.—

Captain Edwin SWALES, D.F.C. (6101V), S.A.A.F., 582 Sqn. (deceased).

Captain Swales was ” master bomber ” of a force of aircraft which attacked Pforzheim on the night of February 23rd, 1945. As ” master bomber,” he had the task of locating the target area with precision and of giving aiming instructions to the main force of bombers following in his wake.

Soon after he had reached the target area he was engaged by an enemy fighter and one of his engines was put out of action. His rear guns failed. His crippled aircraft was an easy prey to further attacks. Unperturbed, he carried on with his allotted task; clearly and precisely he issued aiming instructions to the main force. Meanwhile the enemy fighter closed the range and fired again. A second engine of Captain Swales’ aircraft was put out of action. Almost defenceless, he stayed over the target area issuing his aiming instructions until he was satisfied that the attack had achieved its purpose.

It is now known that the attack was one of the most concentrated and successful of the war.

Captain Swales did not, however, regard his mission as completed. His aircraft was damaged. Its speed had been so much reduced that it could only with difficulty be kept in the air. The blind-flying instruments were no longer working. Determined at all costs to prevent his aircraft and crew from falling into enemy hands, he set course for home. After an hour he flew into thin-layered cloud. He kept his course by skilful flying between the layers, but later heavy cloud and turbulent air conditions were met. The aircraft, ‘by now over friendly territory, ‘became more and more difficult to control; it was losing height steadily. Realising that the situation was desperate Captain Swales ordered his crew to bale out. Time was very short and it required all his exertions to keep the aircraft steady while each of his crew moved in turn to the escape hatch and parachuted to safety. Hardly had the last crew-member jumped when the aircraft plunged to earth. Captain Swales was found dead at the controls.

Intrepid in the attack, courageous in the face of danger, he did his duty to the last, giving his life that his comrades might live.*6

His body was removed from the aircraft in which he gave his life and was interned at the War Cemetery at Leopoldsburg, in Belgium, Section VIII Grave C.5.

In honour of Captain Swales, two memorial stones were laid and revealed outside his Durban High School on Armistice day 2009. One in the Memorial Courtyard of the School and the second on the Memorial Wall of the Natal Mounted Rifles also in Durban. In attendance were both his niece, Professor Edwina Ward, and Lt. Gen. Carlo Gagiano, Chief of the South African Air Force.

In 2013, Swales was also awarded the “Bomber Command” clasp to be worn on the 1939 – 1945 Star already awarded.

Edwin Swales was indeed a very brave man, who through sheer determination managed to save his crew in spite of the dangers facing him. His award was in no doubt deservingly awarded.

The story of pals Edwin Swales and Robert Palmer both of whom won VCs posthumously whilst at RAF Little Staughton.*7

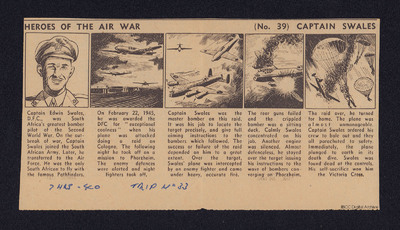

The story of Captain Swales appeared in a newspaper cartoon “Heroes of the Air War”.*8

RAF Little Staughton appears in Trail 29.

Sqn Ldr. Robert Palmer’s story appears in Heroic Tales.

Sources and further reading.

*1 the documents showing Captain Swales’ promotion to the rank of Major only reached the UK authorities after his death and as a result he was cited as being a Captain. (South African Aviation Foundation)

*2 National Archives 582 Operational Record Book AIR-27-2052-18

*3 Supplement 36954, to The London Gazette, 23rd February 1945, published 20th February 1945, page 1070

*4 Middlebrook, M., Everitt. C., “The Bomber Command War Diaries“, Midland Publishing Ltd, 1996

*5 International Bomber Command Centre National Archive website.

*6 Fifth Supplement to The London Gazette, of Friday 20th April 1945. Published on Tuesday 24th April 1945, Supplement 37049, Page 2173.

*7 “Newspaper cuttings concerning awards of Victoria Crosses,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed November 11, 2023,

*8 “Heroes of the Air War (No. 39) Captain Swales,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed November 11, 2023,

*9 Photo The South African Legion of Military Veterans website

*10 South African Aviation Foundation website