Part 5 of this trail, we saw how Sutton Bridge grew into a bustling hub of Allied air training, hosting a mix of British, European, Commonwealth, and American pilots. How the airfield remained under constant threat from Luftwaffe raids, while crowded skies and inexperienced trainees made accidents a grim reality. In 1942, the focus shifted from front-line pilot training to advanced gunnery instruction with the arrival of the Central Gunnery School. Fighter and bomber crews honed their skills in Spitfires, Wellingtons, and Hampdens, while innovative experiments, including rocket-firing Hurricanes, highlighted Sutton Bridge’s role at the cutting edge of aerial warfare. Despite progress, the dangers were ever-present, with both trainees and experienced instructors paying the ultimate price.

In the final part, we witness the slow decline and eventual but inevitable closure of the airfield. How a once vibrant but small airfield became simply a part of history.

Arrival of WAAFs and Local Folklore

During May 1942, Sutton Bridge found itself with in excess of 180 WAAFs arriving, mainly to operate training turrets and to work in the photographic room developing cine reels. The WAAFs were billeted not on the airfield but in small Nissen huts located in various parts of the village. It was one of these WAAFs that added fuel to the story of a pilot flying under the bridge, by claiming she saw it happen, again whilst she was there. No other evidence is available and so, like the first account, it will unfortunately remain just an uncorroborated story passed from generation to generation.

Enemy Attacks and a Safe Haven.

The war was never far away, and once again was brought all that little bit closer on 24th July 1942, when a Dornier 217 dropped its payload on the airfield in the early hours of the morning whilst most were asleep. Several buildings were damaged including hangars, the cinema and the armoury which exploded when all the ammunition inside was hit. Several personnel were also injured mainly from flying debris, and several aircraft were also damaged. The attack certainly brought an early morning wake up call and the war very much closer to home.

Being so close to the Wash, Sutton Bridge was often a safe haven for damaged aircraft either returning from Germany or suffering mechanical difficulties whilst forming up over the Wash. One such incident involved B-17F #41-24460 “RD-A” of the 423BS, 306BG at Thurleigh. The aircraft had been part of ninety B-17s and B-24s sent to Lorient on October 21st 1942. Due to poor visibility, the operation was scrubbed and bombers were ordered to dispose of their bombs in the Wash – a common practice for damaged aircraft or scrubbed missions. During the process, the life-raft latch broke loose allowing the raft to escape and wrap itself around the elevator.

B-17 #41-24460 ‘RD-A’ of the 306th BG that made an emergency landing at RAF Sutton Bridge. (IWM FRE 4418)

After landing on the short space of Sutton Bridge, the problem was soon sorted allowing the B-17 to take off and return for further repairs at its base at Thurleigh. Crowds gathered to see the spectacle as the aircraft thundered along the grassed runway before rising into the air.

Earlier Emergency Landings

It was not the first bomber though, to use Sutton Bridge as safe haven. Prior to this, a Halifax (W1102) from 35 Sqn, also made an emergency landing after it suffered damage on the night of October 14th 1942. The bomber, taking part in operations over Kiel, was hit by flak rendering its starboard outer engine unserviceable and the fuel tank leaking. Despite its difficulties, the crew managed to reach Sutton Bridge with little fuel left to get them home to Gravely. The crew would experience something similar a matter of days later when they had to land another damaged Halifax, this time at RAF Martlesham Heath.

USAAF Arrivals and High-Profile Visits

Sutton Bridge had supported many US airmen in the lead up to their war, training pilots of the Eagle Squadrons. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and America’s entry into the war, USAAF pilots began to arrive here for gunnery training bringing their own unique aircraft with them. Some of these included P-38 ‘Lightnings’, an aircraft unknown to the British airmen at Sutton Bridge. Other US visitors included Brigadier-General James Doolittle and an entourage of high ranking officials. Arriving on a Douglas C-47 ‘Skytrain’, they were here to inspect the training methods of the Gunnery School and try out the Spitfires for themselves.

Even with experienced pilots and gunners, mishaps continued to happen. As the summer of 1942 led into the autumn and eventually winter, so the cold, fog and frosts began to return too.

Accidents and Operational Hazards

But the cold weather was not the only problem pilots had to contend with. Even though, those who attended the gunnery school had already received operational experience, it didn’t stop them having accidents. Between August 1st 1942 and New Year 1943, there were no less than fourteen crashes on the airfield all relating to undercarriage issues; either a heavy landing, blown tyres or a pilot’s mishandling of the aircraft.

Winter Challenges, Early 1943

With heavy snows in January 1943, present aircraft had to be stored undercover, being pushed by hand, into the hangars. Waterlogged ground froze, and ice became the norm. What flying could be done could only be done in Magisters, the Spitfires flimsy flaps and undercarriages being too prone to damage in such appalling conditions. By the end of January and beginning of February, servicing also become an issue with around two-thirds of the sixty available aircraft requiring remedial attention.

Spring Accidents, more Losses and more Changes

As the winter changed to spring the weather turned, the ground thawed and flying took place once more. On 10th April, a Wellington of the CGS, Wellington IA N2865 piloted by Flt. Lt. Terence C. Stanbury, collided in mid air whilst undertaking a training exercise with Spitfire IIa (P7677) piloted by Flt. Lt. Ernest H. Griffith of the RAAF. The two aircraft were performing gunnery manoeuvres over Abbots Ripon not far from Alconbury in Huntingdon, when they accidentally collided sending both aircraft to the ground.

Flt. Lt. Griffith managed to bale out suffering minor injuries and was returned to Sutton Bridge where he was treated before returning to flying duties. The Wellington crew were not so fortunate however, and all six were killed. The crew was a truly multinational one consisting of a Scot, a Canadian, and two Australians. The Pilot, Flt. Lt. Stanbury lies in Sutton Bridge churchyard.*18

Leadership within the CGS changed hands on numerous occasions during its wartime history; one of the more famous associated with it being New Zealander Wg. Cdr. Alan C. Deere, whose achievements overshadowed most who followed him. On appointment to lead the Pilot Gunnery Instructor Training Wing, (a part of the CGS) on October 21st 1943, he would have twenty-two kills to his name, an ideal candidate to lead such a school.

1944 – Departure of the Central Gunnery School

By February 1944, a further reorganisation occurred and it was decided that the Central Gunnery School (CGS) would move on from Sutton Bridge. After two productive years, the school had more than demonstrated its value, but its departure left a sense of uncertainty. With Wing Commander Alan Deere posted to a desk job and the demand for new aircrew beginning to decline, the future of the airfield seemed in doubt. A review, downgrading, or even closure suddenly appeared possible.

For a time, Sutton Bridge became ‘spare’ and was placed in a state of ‘care and maintenance’, administered by RAF Peterborough while its long-term role was considered. Yet its story was far from over. With Peterborough heavily committed, Sutton Bridge was soon called upon to take on new duties. When the runways at RAF Newton (Peterborough’s satellite) required reseeding, its resident 16 (Polish) Service Flying Training School was temporarily relocated to Sutton Bridge. From early 1944 until August, the Polish unit brought a new but temporary life to the airfield before eventually returning to Newton once more.

Although winding down, the summer months continued to bring further activity. Between May and November an American unit, the 1st Gunnery & Towed Target Flight (1 G&TTF), arrived to operate alongside No. 1 Combined Combat Gunnery School, then based at RAF Snettisham. Their task was to provide target-towing services, a role previously carried out at Sutton Bridge by RAF flights equipped with Vultee Vengeance aircraft. Surplus Vengeances were duly handed over to the Americans, who continued the work with their own crews.

Meanwhile, No. 7 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit (7 (P)AFU, officially based at Peterborough, made increasing use of Sutton Bridge as an overflow for both day and night flying. Among its pupils were French trainees, who formed a distinct French wing within the unit, flying Miles Masters and Airspeed Oxfords. For a time this group carried the informal title of “French SFTS,” although this was later dropped.

As 1944 progressed, training pressures shifted. After D-Day, the demand for new pilots eased, and courses at Sutton Bridge became more general in nature. In December, 7 (P)AFU was reorganised and re-designated No. 7 Flying Training School (FTS). Training was split between the two sites: single-engine work at Peterborough, twin-engine training at Sutton Bridge. At the helm was Wing Commander David Kinnear, AFC, AFM, whose leadership steered the school through this transitional period.

For Sutton Bridge, this change marked the final stage of its wartime flying role. With nearby Sibson closed for runway maintenance, 7 FTS continued to operate from Sutton Bridge into the post-war years. The school remained there until 1946, making it the last operational flying unit to be based at RAF Sutton Bridge. After its departure, the airfield’s role shifted once again, becoming a relief landing ground and maintenance site, closing this chapter on its remarkable contribution to the war effort.

1946 – The End of an era

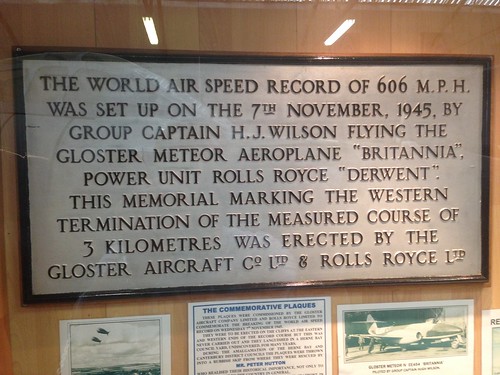

After its inevitable closure to flying, the site became a storage facility utilised by 58 Maintenance Unit (MU), whose work included servicing Derwent 8 and 9 jet engines, powering the RAF’s latest front-line aircraft, the Vampire and Meteor. For four more years Sutton Bridge was at the heart of this vital engineering effort, before activity gradually wound down once again as the station moved towards demobilisation.

Now surplus to requirements, it closed for good. This marked the end of the line for Sutton Bridge; as a small grass airfield with basic facilities, it was no longer capable of providing a use to a modern Air Force who had moved from piston engined aircraft to fast jets and the nuclear age. With a reorganisation of the entire air force likely, this small but highly significant site was abandoned, and all remaining military personnel departed locking the gates behind them; thus ending three decades of aviation activity.

Post War Legacy

From the 1920s through its wartime years, Sutton Bridge was a hive of activity and purpose. From the 1920s to the Central Gunnery School, training instructors in fighter and bomber gunnery, to the Fleet Air Arm squadrons working up in Ospreys, Skuas, and Nimrods over the Wash, the airfield was a crucible where skill, courage, and determination were forged. Advanced pilot training by 7 (P)AFU and 7 FTS saw cadets mastering single – and twin-engined aircraft, including Wellingtons, Hampdens, Spitfires, and Mustangs. Visits by senior figures, such as Air Chief Marshal Ludlow-Hewitt, underscored the station’s strategic importance. Hundreds of pilots and aircrew honed their skills at this small but significant airfield, readying themselves to defend Britain’s skies during the darkest days of 1940–41.

Sutton Bridge Today

Today, Sutton Bridge airfield has largely returned to the rhythms of the countryside, its runways removed and its technical and accommodation areas absorbed into the Wingland Enterprise Park – home to a large power station and a vegetable processing facility where only one of the original Bellman hangars still stands – a quiet sentinel to the airfield’s former life.

Sutton Bridge was far more than an RAF outpost. Its runways and the associated gunnery ranges served both the RAF, the Fleet Air Arm and the USAAF, becoming a crucial hub in Britain’s pre-war and wartime training network. Here, generations of instructors and trainees honed their skills, learning the art of aerial combat, navigation, and gunnery in an environment that was both demanding and dangerous.

The graves in St. Matthew’s churchyard are a poignant reminder of the risks inherent in training pilots. For every life lost, many others went on to defend Britain during the Battle of Britain and beyond, their courage and commitment standing as a beacon when the nation’s fate seemed uncertain. Between the opening of Sutton Bridge and the official end of the Battle of Britain, 525 trainees passed through its gates, with 390 qualifying for the Battle of Britain Clasp, a testament to the station’s vital contribution to the war effort.*19

Today, only a handful of tracks and a solitary building, believed to be a former squadron office, mark the site. Amidst polytunnels and vast potato stores, the airfield’s presence is almost invisible.

A memorial, incorporating the bent propellor of Hurricane L2529 of 56 OTU that crashed in March 1941, was erected in 1993, near to the swing bridge, and stands in quiet tribute, commemorating all nationalities who served at Sutton Bridge, ensuring that the sacrifices and achievements of those who trained and served here are not forgotten.

As for the range at Holbeach, the very reason for RAF Sutton Bridge’s origin, it remains a vital asset to both the Royal Air Force and the USAF, having regular visits from Typhoons, F-15s, Ospreys, Apache Helicopters and more recently F-35s. On retirement of the RAF’s Tornado in 2019, it was overflown by a formation of three from RAF Marham. It remains publicly accessible and provides an exciting reminder of the history of aviation in and around the area of Sutton Bridge.

The full story can be read in Trail 3 – Gone but not Forgotten.

Sources and Further Reading (Sutton Bridge)

*1 Francis, P. “British Airfield Architecture” Patrick Stephens Ltd. 1996

*2 Goodrum,, A., “School of Aces” Amberley Publishing 2019.

*3 Royal Air Force Quarterly Vol 16. No.1. December 1944 (via Google books)

*4 There is no official evidence to support this claim but ‘eye-witnesses’ claim to have seen it carried out (as mentioned in Goodrum, 2019)

*5. Air of Authority / RAFweb – No. 801 Squadron movements, listing Sutton Bridge visits in July 1933, May 1935 and January 1938.

*6. Air of Authority / RAFweb – No. 802 Squadron movements, listing Sutton Bridge visits in August 1934 and May 1935.

*7. Royal Navy Research Archive – RAF Worthy Down station history, noting 803 Squadron’s move to Sutton Bridge on 5 February 1939 and 800 Squadron’s linked ship-to-shore activity in spring 1939.

*8 BAE Systems Website accessed 30.3.25.

*9 National Archives AIR 27/1553/1; AIR 27/1558/1

*10 Verkaik, R., “Defiant“. Robinson. 2020

*11 The National Archives, AIR 33/10, “Report No. 11. Visit to Sutton Bridge on 3 May 1940. Notes by the Inspector General,” dated 14 May 1940, signed Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt.

*12 Hamilton-Paterson, J., “Empire of the Clouds” Faber & Faber 2011

*13 Waterton, William Arthur., “The Quick and the Dead“. Grubb Street. 2012

*14 Goodrum,, A., “School of Aces” Amberley Publishing 2019.

*15 Chorley, W.R. “Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War – 1942.” 1994, Midland Counties.

*16 Goodrum,, A., “School of Aces” Amberley Publishing 2019.

*17 Commonwealth War Graves Commission website

*18 – Aircrew Remembered website. accessed 30/8/25

*19 Goodrum,, A., “School of Aces” Amberley Publishing 2019.

National Archives: AIR 27/1558/1; AIR 27/1553/1; AIR 27/1514/2; AIR 27/1514/1; AIR 27/589/1; AIR 27/379/41

Goodrum. Alastair, “Through adversity” 2020. Amberley Publishing Limited

Flight Safety Network website