As part of the ‘American Ghosts’ trail around the borders of Northampton and Cambridgeshire, we move away from Kimbolton to an airfield that is synonymous with both the first and last bombing raids of the American Air War in Europe. We travel a few miles north, here we find a truly remarkable memorial and an area rich in history. We go to RAF Grafton Underwood.

RAF Grafton Underwood. (Station 106)

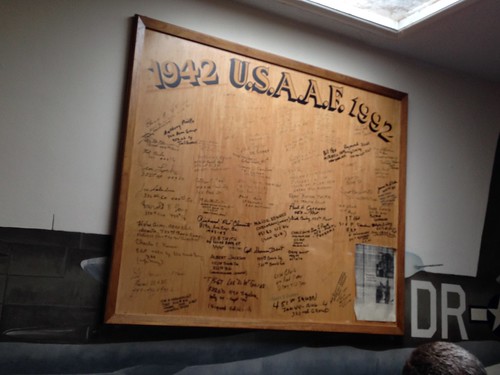

Construction of Grafton Underwood began in 1941, originally part of the RAF’s preparation of the soon to be defunct bomber group to be based in this region. But with the birth of the Eighth Air Force on January 28th 1942, it would become the USAAF’s first bomber base, when the 15th Bomber Squadron arrived after sailing on the SS Cathay from the United States.

The original idea for the ‘Mighty Eighth’ was to house a total of some 3,500 aircraft of mixed design in 60 combat groups. Four squadrons would reside at each airfield with each group occupying two airfields, this would require 75 airfields for the bomber units alone. This figure was certainly low and it would increase gradually as the war progressed and demand for bomber aircraft grew.

The terrible attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbour diverted both attention and crews away from the European Theatre, but in April / May 1942 the build up began and American forces started to arrive in the UK.

With ground staff sailing across the Atlantic and aircrews ferrying their aircraft on the northern route via Iceland, the first plain olive drab B-17Es and Fs of the 97th BG set down on July 6th 1942, two squadrons at Polebrook and two at Grafton Underwood.

The sight of American airmen brought a huge change to life in this quiet part of the countryside. Locals would gather at the fence and stand watching the crews as if they were something strange. But as the war progressed, the Americans would become accepted and form part of everyday life at Grafton Underwood.

Eventually the airfield would be complete and although it would go through development stages, it would remain a massive site covering around 500 acres of land.

A total of thirteen separate accommodation and support sites would be built; two communal; seven officers; a WAAF site; a sick quarters and two sewage treatment sites to cope with upward of 3,000 men and women who were to be based here.

The accommodation was based around an octagonal road design, the centre piece being the ‘Foxy’ cinema in Site 3 the main communal site. Roads from here took the crews away to various sites hidden amongst the trees of the wooded area. All theses site were located east of Site 1, the main airfield itself.

Grafton would have three runways; runway 1 (6,000 ft) running north-east / south-west, runway 2 (5,200 ft) running north-west / south-east and runway three (4,200 ft) running north to south, all concrete enabling the airfield to remain active all year round.

B-17 ’42-97948′ BK-U, “Hell on Wings” 384th BG, 546th BS. Prior to being lost on 11th October 1944. (IWM UPL 12946)

A large bomb store was located to the north-western side of the airfield, served by two access roads, it had both ‘ultra heavy’ and ‘light’ fuzing buildings; with a second store to the north just east of the threshold of runway 1. Thirty-seven ‘pan’ style hardstands and three blocks of four ‘spectacle’ hardstands accommodated dispersed aircraft around the perimeter track. Surprisingly only two hangars were built, both T2 (drg 3653/42) one in the technical area to the east and the second to the south-west.

On May 15th 1942, Grafton officially opened with the arrival of its first detachment. The 15th Bombardment Squadron (Light) arrived without aircraft and had to ‘borrow’ RAF Bostons for training and deployment. As yet there was no official directive, and so crews had little to do other than bed in. The 15th BS remained here until June 9th 1942 whereupon they moved to their new base at RAF Molesworth and began operations in their RAF aircraft supported by experienced RAF crews. This move coincided with the arrival of the main body of the Eighth Air Force on UK soil and the vacancy at Grafton was soon filled with B-17s of the 97th BG (Heavy).

Only activated in February that year, the 97th consisted of four Squadrons: at Polebrook were the 340th BS and the 341st BS, whilst at Grafton were the 342nd BS and the 414th BS. Whilst State side they flew submarine patrols along the US coast, but with clear skies and little in the way of realistic action, the ‘rookie’ crews would be ill prepared for what was about to come.

With the parent airfield at RAF Polebrook providing much of the administration for the crews, it was soon realised that gun crews, navigators, pilots and radio operators were poorly trained for combat situations. Quickly thrown together many could not use their equipment – whether a radio or gun – effectively and so a dramatic period of intense training was initiated. The skies around Grafton and Polebrook, quickly filled with the reverberating sound of the multi-engined bombers.

These early days were to be hazardous for the 97th. On August 1st, B-17 “King Condor” would crash on landing at Grafton Underwood. The aircraft’s brakes failed, it overshot the runway, went through a hedge and hit a lorry killing the driver.

B-17 41-9024 ‘King Condor’ Crash landed August 1st, 1942 pilot Lt Claude Lawrence ran off runway, through hedge and hit a truck, killing driver John Jimmison. (IWM UPL 19654)

On August 9th, the atmosphere at Grafton became electric, as orders for the first mission came through. Unfortunately for the keen and now ‘combat ready’ crews, the English weather changed at the last-minute and the mission was scrubbed. This disappointment was to be repeated again only 3 days later, when further orders came through only to find the weather changing again and the mission being scrubbed once more.

In the intervening days the weather was to play another cruel joke on the group claiming the first major victim of the 97th. A 340th BS B-17E ’41-9098′, crashed into the mountainside at Craig Berwyn, Cadair Berwyn, Wales, killing all 11 crew members. A sad start indeed for the youngsters.

Eventually though the weather calmed and on August 17th 1942, at 15:12, twelve aircraft took off from Polebrook and Grafton and headed south-east over the French coast. Not only was it notable for its historical relevance as Mission 1, but on board one of the B-17s was Major Paul Tibbets who later went on to drop the atom bomb on Hiroshima 3 years later. If this wasn’t enough, a further B-17, ’41-9023′, “Yankee Doodle”, also contained the Commanding General of the Eighth, Ira Eaker, – truly a remarkably important and historical flight indeed.

The 97th would go on to attack numerous targets including airfields, marshalling yards, industrial sites and naval installations before transferring to the Twelfth Air Force and moving away from Grafton to the Mediterranean in November 1942.

There then followed a quiet spell, for Grafton. A short spell between September and December 1942 saw the heavy bombers of the 305th BG reside at Grafton before moving off to Chelveston and another short spell for the heavies of the 96th BG in the latter half of April 1943 whilst on their way to Great Saling in Essex. It wouldn’t be until early June 1943 that Grafton would once again see continuous action over occupied Europe.

Activated at the end of 1942, the 384th BG (formed with the 544th, 545th, 546th and 547th BS) would train for combat with B-17Fs and Gs, move to Grafton via Gowen Field, Idaho, and Wendover Field, Utah, and perform as a major strategic bomber force. Focussing their attacks on airfields, industrial sites and heavy industry deep in the heart of Germany, they would receive a Distinguished Unit Citation (D.U.C) for their action on January 11th 1944. Targets included the high prestige works such as: Cologne, Gelsenkirchen, Halberstadt, Magdeburg and Schweinfurt. They would take part in the ‘Big Week’ attacks in February 1944, support the Normandy invasion, the break out at St. Lo, Eindhoven, the Battle of the Bulge and support the allied advance over the Rhine. A further DUC came on 24th April 1944 when the group led the 41st Wing in the attack against Oberpfaffenkofen airfield and factory. Against overwhelming odds, the group suffered heavy losses but took the fight all the way to the Nazis.

A dramatic photo of B-17 Flying Fortress BK-H, (s/n 42-37781) “Silver Dollar” of the 546th BS, 384th BG as it goes down after losing its tail. (IWM FRE1282)

Just as Grafton had played its part in the opening salvo of American bombings, it was to be a part of the last. On April 25th 1945, the last bombing raids took place over south-east Germany and Czechoslovakia. Mission 968 saw 589 bombers and 486 fighters drop the final salvos of bombs of the war on rail, industrial and airfield targets, shooting down a small number of enemy aircraft including an Arado 234 jet. Last ditch efforts by the remnants of the Luftwaffe claimed 6 bombers and 1 fighter, before the fight was over. After this all remaining missions were propaganda leaflets as bombs were replaced by paper.

Two years after their arrival the 384th departed for France, eventually returning to the US in 1949 and disbandment. Their departure left Grafton quiet, it was retained by the RAF under care and maintenance and then finally in 1959 declared surplus to requirements and sold off.

In the short two years of being at Grafton, the 384th had amassed 9,348 operational sorties, in 314 missions. They dropped 22,415 tons of explosives and lost 159 aircraft for the shooting down of 165 enemy aircraft. They received two Distinguished Unit Citations and over 1000 Distinguished Flying Crosses. A remarkable achievement for any bomb group.

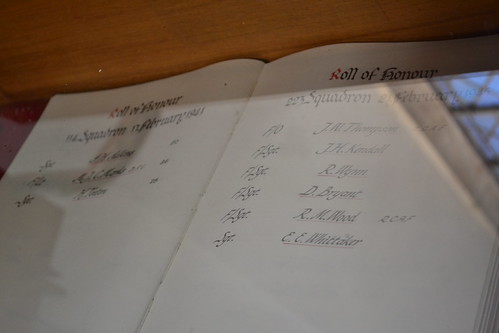

Grafton today is very different to how it was in the mid 1940s. But before you go to the airfield, you must visit the local church. Passing through the village you’ll see a signpost for the church, park here and walk up the short path. Approaching the church, roughly from the East, you see a dark window which is difficult to make out. However, enter the church and look back, you will see the most amazing stained glass window ever, – the vibrant colours strike quite hard. This window commemorates the men and women of the 384th Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force who were stationed at here at Grafton Underwood.

Next to it, someone has placed a handwritten note with the picture of a very young man 2nd Lt. Thomas K Kohlhaas and details of the crew of B-17 ‘43-37713’ “Sons o’ Fun”. It states that he, along with 3 others of the crew, were murdered by German civilians after their aircraft was downed by flak on 30th November 1944. This is a very moving and personal place to be and a poignant reminder of what these young men were facing all those years ago.

When you leave the church, look on the wall of the porch and you will see two dedications. These list the location and names of trees, dedicated to the personnel of the Mighty Eighth, that have now replaced the runways on the airfield. Unfortunately these are on private land and for some very odd reason, not accessible.

Leave the church, turn left into the village, following the stream and then turn left up the hill. The memorial is on your right. Like most American memorials of the USAAF, it has the two flags aside the memorial which is well-kept. When I visited, ‘the keeper’ (who has since become a good friend of mine) was there and we chatted for ages. The memorial stands on what was the 6000 ft main runway and when you look behind you, you see what is left of it, a small track used for estate business. Other than this and a few inaccessible sections, the remains of the airfield have gone and it is open agriculture once more.

Grafton, like Kimbolton, is split by the road. Leaving the memorial drive back to the village, turn left and follow the road. Along on the left is the former technical site, a few small huts still stand here used by the local farmer. Also, a few feet from the roadside would have been the perimeter track and dispersal pans. What is left of the main entrance, now nothing more than a large blue gate, can be seen as you pass. Odd patches of concrete can also be seen through the thick trees but little else. Then a little further along, passed the equine sign, is another blue gate. Park here. This is the entrance to Grafton Park, a public space, and what was the main thoroughfare to the mess, barracks and squadron quarters. Grafton housed some 3000 personnel of which some 1600 never returned. It is immense! Walking along the path, you can just see the Battle Headquarters, poking out of the trees, the site is very overgrown and nature is claiming back what was once hers. The roads remain and are clearly laid out, some having been recovered with tarmac, but careful observations will see the original concrete beneath. Keep on the ‘Broadway’ and you will pass a number of side roads until you come to the hub. This forms a central octagonal star, off from which were the aptly named: ‘Foxy’ cinema, mess clubs and hospitals. Each road taking you from here, site 3, to the various other sites a short distance away. Careful observations and exploring – there are many hidden ditches and pits – will show foundations and the odd brick wall from the various buildings that remain. A nice touch to the hub, is that it is now a grassed area with picnic tables.

You do lose a sense of this being an airfield; the trees and vegetation have taken over quite virulently and hidden what little evidence remains. Exploring the area, you will find some evidence, but you have to look hard. Walk back along the Broadway, and take the first turn left. Keep an open to the right, and you will see other small buildings, the officers’ quarters and shelters – this was site 4. Again, very careful footing will allow some exploration, but there is little to gain from this.

Considering the size of Grafton Underwood, and then fact that 3000 men and women lived here, there is little to see for the casual eye. A beautiful place to walk, Grafton’s secrets are well hidden; perhaps too well hidden, but maybe the fact that it is so peaceful is as a result and great service to those that fought in that terrible battle above the skies of Europe directly from here.

There is a superb website dedicated to the crews of Grafton Underwood and it can be found at: http://384thbombgroup.com

Grafton Underwood was originally visited in 2014, this post has been updated since then. It forms part of Trail 6.

![General Arnold with Colonel Frederick W Castle, Brigadier General Curtis LeMay, General Williams and General Anderson during a visit to Bury St Edmunds (Rougham), home of the 379th Bomb Group. Image stamped on reverse: 'Passed for publication 3 Sep 1943.' [stamp] nand '282085.' [censor no.] A printed caption was previously attached to the reverse however this has been removed. Associated news story: 'American Air Forces G.O.C. Meets The](https://i0.wp.com/www.americanairmuseum.com/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/freeman/media-456751.jpg)