After Part 1, we return to RAF Winfield, where an ‘odd’ visitor arrives. We also see the post war demise of Winfield into the site it is today.

At the end of the war many Polish units and displaced persons were pulled back to the U.K. in preparation for their repatriation into civilian life and for some return to their native country. Winfield became the site of one such group; the 22 Artillery Support Company (Army Service Corps, 2nd Polish Corps) who whilst fighting in the Middle East and Italy adopted a rather odd mascot. He became known as Wojtek, a Syrian bear who was officially given the rank of Private in the Polish Army, and who ‘fought’ alongside them as one of their own.

Wojtek the Syrian bear adopted by the Polish relaxing at Winfield Airfield, the unit’s temporary home after the war.*1

After finding the bear as a young cub wrapped around the neck of a small Iranian boy, Lance Corporal Peter Prendys took him and adopted him. After the war, on October 28th 1946, the Polish Army along with the bear arrived at Winfield Displaced Persons Camp – little did they know what a stir Wojtek would cause.

As displaced persons the Polish men would venture into nearby Berwick, where the locals grew fond of them and drinks flowed in abundance. Wojtek would go with them, becoming a familiar, if not unorthodox, site amongst the streets and bars or Berwick. This cigarette smoking, beer loving character, often causing a stir wherever he went. He became renowned in the area, the local villagers would flock to see him. He joined in with the frolics and loved the life that he was being allowed to live.

As a bear he loved the rivers and the River Tweed flows only a short distance from Winfield, rich and fast flowing it is abundant in that other commodity – Salmon. However, Wojtek was under strict orders not to swim alone nor stray onto the airfield which although closed, could still provide a danger for him if seen.

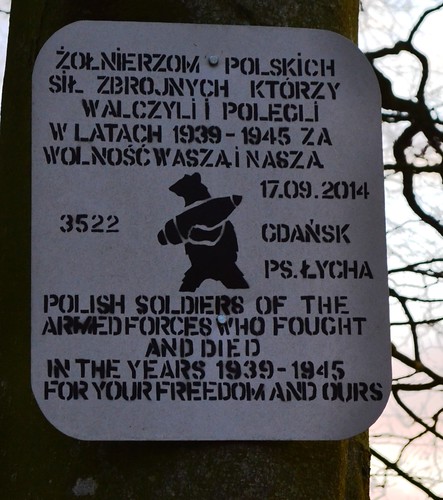

Wojtek became part of local history, eventually, a year after their arrival, the Polish unit were demobbed and they moved away. Wojtek was given to Edinburgh Zoo to look after, who did so until his death at the age of 21 in 1963. A statue stands in Princess Street Gardens beneath Edinburgh Castle as a reminder of both him and the Polish troops who were stationed at Winfield camp. A second statue of Wojtek stands in the centre of Duns, the village not far from Charterhall. The Wojtek Memorial Trust, set up in his honour, aims to promote both educational and friendship links between the young people of Scotland and Poland, an aim it tirelessly works towards today.

After the Polish troops left, Winfield was allocated to the USAF, and earmarked for development, but this never materialised and the site was left dormant. Winfield then reverted back to RAF control some five years later in October 1955, whereupon it was disposed of and sold off.

A small group of private flyers reopened the site, renovating the watch office and utilising a small hangar on the north of the airfield. This operation has now ceased and the watch office has sadly fallen into disrepair, it windows missing and open to the elements. The demise of Winfield and its subsequent decay has begun.

Winfield airfield lies between two roads, a further public road passes through the site although this was seen to be gated at the southern end. The most prominent feature is by far the Watch Office, a two-story design built to design 15684/41, having walls some 13.5 inches thick as was standard for all night-fighter stations (but different to the one at Charterhall).

Other buildings also remain to the west on the main airfield site but these are only small and very few in number. The accommodation sites have all been removed, however, there are some buildings remaining in the former WAAF site to the north of the airfield. Located down a track just off the B4640, these buildings appear to be latrines and a possible WAAF decontamination block, with other partial remains nearby. Drawing numbers for these are unclear, (but appear to be 14420/41 and 14353/41) indicating WAAF (Officer and sergeant) quarters. Other buildings on this site look to have been a drying room, water storage tank and a picket post. Heading further south along this track leads to a small pond, here is a local design Fire Trailer shelter: a small brick-built building no more than about seven feet square. Presumably this pond was used to fill the fire trailer in cases of fire or attack and was located midway between the WAAF site and the main airfield. Also on this site, which is part of the Displaced Persons Camp, is a makeshift memorial to the Polish Armed Forces, dotted around the ground are a number of metal parts partially buried in the soil.

The airfield runways and perimeter tracks are still in place, and years of both decay and locals using them to practice their driving skills on, have taken their toll. Like Charterhall, Winfield was also used as a motor racing circuit, although not to the same extent that Charterhall was. On one occasion though, as many as 50,000 spectators were known to have visited the site on one day alone!

Winfield like its parent site has now become history, the remnants of its past linger on as final reminders of the activities that went on here in the 1940s. The night fighter pilots who pushed the boundaries of aircraft location and interception are gradually fading away; the dilapidated buildings too are gradually crumbling and breaking apart. Inch by inch these sites are disappearing until one day soon, perhaps even they will have gone along with the brave young men who came here to train, to fight and in many cases to die.

As we leave the remnants of Winfield and Charterhall behind, we continue North to our next trail; nearing Edinburgh we take in more of Scotland’s natural beauty and even more tales of its wonderful but tragic aviation history.

My sincere thanks go to both Mr. and Mrs. Campbell for their hospitality and the help in touring these two sites. The history of both Charterhall and Winfield can be read in Trail 41.

Sources and Further Reading – RAF Winfield

*1 Photo IWM collections No.HU 16548.

The Polish Scottish Heritage website provides information about the scheme.