The end of training flights in the Second World War in the quiet and blue skies of the United States, were occasionally ‘celebrated’ with flyovers and ‘buzzing’ of the home town of family or girl friend

The end of training flights in the Second World War in the quiet and blue skies of the United States, were occasionally ‘celebrated’ with flyovers and ‘buzzing’ of the home town of family or girl friends. Whilst this unofficial activity was frowned upon, in general, a blind eye was turned by Commanding Officers of the various Groups. However, one such activity was not taken quite so lightly, and almost led to the end of a promising career before it had even started.

At RAF Molesworth (Station 107) not far from Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, the 303rd Bomb Group (BG) had been serving the Allied offensive since mid September 1942. They had taken heavy casualties after participating in many prestige missions including the disastrous August and October raids on the ball-bearing plant at Schweinfurt. The invincibility of the heavily armed B-17 was very quickly shown to be a myth.

After a period of calm, primarily due to persistent bad weather rather than any significant strategic military decision, the USAAF was allowed unofficial time to recuperate, rebuild and rearm. During this period, new recruits and aircraft poured into the United Kingdom via either the Northern or the Southern transit routes over the Atlantic Ocean.

On one of these aircraft was Lt. Jack Watson, a ‘green’ pilot’ who had recently completed his training, and was now on his way to fight in a war a long way from his Indianapolis home.

A fresh faced 2nd Lt. Jack Watosn who bravely brought home his burning and crippled B-17 bomber after ordering his crew to bail out. (IWM UPL 32160)

A fresh faced 2nd Lt. Jack Watosn who bravely brought home his burning and crippled B-17 bomber after ordering his crew to bail out. (IWM UPL 32160)On eventual arrival at Molesworth, Lt. Watson was soon to experience for himself the horrors and reality of war. On January 11th 1944, he was part of a 291 bomber force attacking both the FW190 production factory as Oschersleben and the Junkers factory at Halberstadt, Germany. On what became one of the blackest days for the Group, eleven out of the forty aircraft dispatched were lost, an attrition rate of just over 25%, which was also the highest loss of the entire force.

On the inward flight, the weather, which had dogged much of the winter, closed in over the continent. A recall message was sent out, the 2nd and 3rd Divisions turning for home, but it was ignored by Brigadier General Robert F. Travis, 1st Bombardment Division Commander in the lead plane – ‘The Eight Ball‘. Original orders were to bomb by visual methods but if cloud cover prevailed then pathfinder Liberators were to mark the target.

As the weather had deteriorated, cloud being present as high as 24,000 feet, fighter cover was all but withdrawn. The bombers were now virtually on their own and much smaller in number.

Alerted early on, the Luftwaffe had managed to form an enormous welcoming party for the now weakened force. It would be the strongest collection of Luftwaffe aircraft since the October raids, and it was waiting, eager for blood.

The first contact between the two forces was made over the shallow waters of the Zuiderzee on the inward flight. A collection of rocket-firing fighters launched a gruesome attack on the lead section of the 303rd, an attack that lasted for several hours and took out numerous aircraft.

From the Initial point (IP) to the target, flak was light but accurate, more aircraft took hits and further damage was sustained by the formation. Those bombers that did get through managed to bomb the target, the accuracy of which was considered ‘excellent’.

On the return flight B-17F #42-29524 ‘Meat Hound‘, piloted by Lt. Jack Watson was attacked again by waves of enemy fighters who zoned in on the bomber and its supporting formation. With many aircraft now crippled, the B-17s were easy targets for the fierce and determined Luftwaffe defenders.

Lt. Watson’s aircraft, (a B-17F-55-BO, which had previously been assigned to the 306th BG transferring to the 303rd in July 1943), was hit hard over Durgerdam. The damage looked terminal, two engines were on fire, there was substantial damage around the wing root and the left elevator had been shot completely off. With such damage, not only was the aircraft difficult to control but it was losing vital airspeed and altitude as well.

Lt. Watson, gave the bail out order, holding the aircraft steady until all the crew had departed. Lt. Watson, who had by then put the aircraft on automatic pilot, was himself preparing to jump, but the thought of the cold waters below forced his retreat to the cockpit and the challenge of getting home alone.

Of those who did jump, four fell into the Ijsselmeer and sadly drowned, and another four were caught by occupying forces and sent to POW camps. The ninth, Lt. Col. Clayton David, the Co-Pilot, managed to evade capture eventually making his way back to England. Clayton’s journey took him through Holland and Belgium and on into France, where he headed south, eventually crossing the Pyrenees into Spain. From there, he reached Gibraltar eventually returning to England in May 1944, four months after he was reported as ‘Missing in Action.’ For his efforts he received the Purple Heart*1.

Lt. Watson, now alone in the crippled B-17 fought on, keeping the aircraft flying toward England. Once over home territory he brought the aircraft down through the thick cloud that had dogged so many of Britain’s airfields that winter, landing at RAF Metfield, an American Fighter airfield home at that time to the 353rd Fighter Group.

So severe was the fire on the aircraft that it took fire crews a considerable time to extinguish it. These crews were not only amazed to see just one crewman exit the aircraft, but also to find an unexploded shell sitting directly behind the pilots seat.

B-17 ‘Meat Hound‘ on the ground at Metfield, Suffolk after landing with two burning engines. The aircraft was subsequently written off and salvaged for usable parts. (IWM UPL 32171).

B-17 ‘Meat Hound‘ on the ground at Metfield, Suffolk after landing with two burning engines. The aircraft was subsequently written off and salvaged for usable parts. (IWM UPL 32171).On his arrival back at Molesworth, Lt Watson received a telegram sent by New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, forgiving Watson for his villainous activity previously in late 1943.

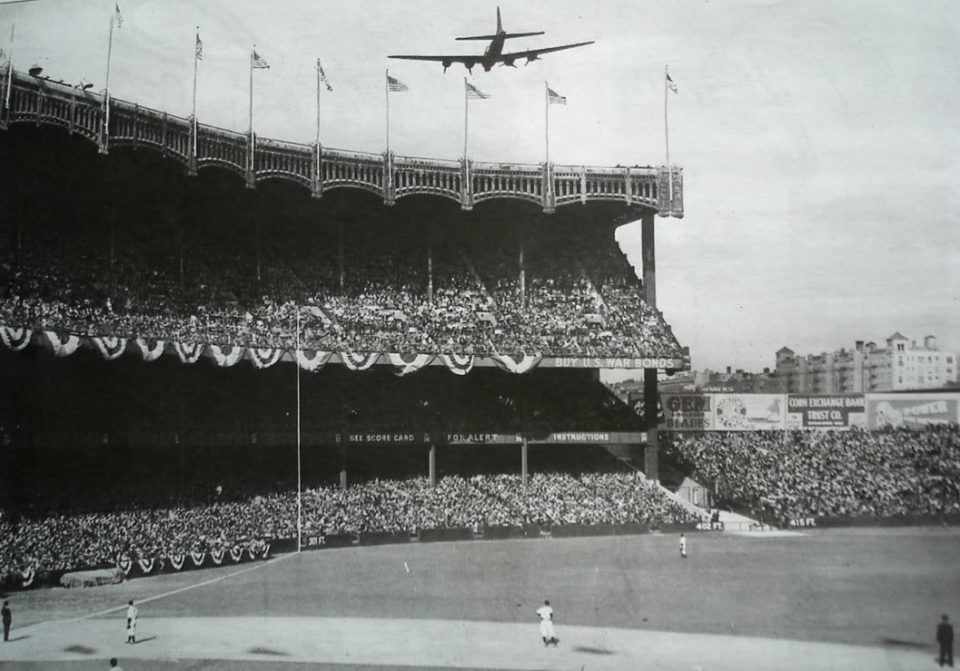

It was at this time that Watson along with three other pilots; 2nd Lts. Robert Sheets, Elmer Young, and Joseph Wheeler, buzzed the World Series game between St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees at the Yankee Stadium, New York. Mayor LaGuardia was so incensed by the action at the time, that he insisted Watson and the others be disciplined, court martial proceedings being instigated as soon as the four landed in Maine*2.

However, it was not to be, the top brass needing every aircraft and crewman they could muster, sent the four on their way with a $75 fine and a stiff telling off!

Although tinged by the sad loss of his crew, the villain of the World Series’ Buzzing, had gone on to prove himself more than a worthy pilot, making history in more ways than one.

A Boeing B-17 ‘buzzes’ the Yankee stadium October 5th 1943. (Author unknown).*3

The crew of ‘Meat Hound‘ were:

Pilot – 2nd Lt. Jack Watson (Returned to Duty)

Co-Pilot – Lt Col. Clayton David (Evaded)

Navigator – 2nd Lt. John Leverton (POW)

Radio Operator – Stf. Sgt. Harry Romaniec (KIA)

Bombardier – 2nd Lt. Vance Colvin (KIA)

Flight Engineer/Top Turret Gunner – Stf. Sgt. Sam Rowland (POW)

Right Waist Gunner – Sgt. William Fussner (KIA)

Left Waist Gunner – Gene Stewart (POW)

Tail Gunner – Sgt. Roman Kosinski (POW)

Ball Turret Gunner – Sgt. Fred Booth (KIA)

The B-17F, #42-29524, was delivered to Denver 31st December 1942; then assigned to the 423rd BS (306th BG) as ‘RD-D’ at Thurleigh 2nd March 1943. It was later transferred to the 358th BS (303rd BG) as ‘VK-K’ based at Molesworth on 30th July 1943.

For their efforts in this mission, the 303rd Bomb Group were awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation, the only time the entire unit achieved such an accolade.

This and other similar stories appears in Heroic tales of World War 2.

Sources and Further Reading.

Missing Air Crew Report 4269

*1 Herald-Whig Obituaries Website accessed 27/5/19

*2 303rd BG website ‘Outfield Fly’ by Hap Rocketto accessed 27/5/19

*3 Photo appeared in ‘Old-Time Baseball Photos and Essays’, blogsite. accessed 27/5/19