This airfield is the most northerly one in Cambridgeshire. It borders two counties and has its origins as far back as World War I. It was a small airfield, but one that played a major part in both the First and Second World Wars. It sat only a short distance from its parent airfield, an airfield that became so big it absorbed it. Today we visit the airfield that was RAF Collyweston.

RAF Collyweston

Throughout their lives, both airfields would go through a number of dramatic changes, especially as new ideas, concepts or advancements in technology were made. The biggest initial change may have been as a result of Major Smith-Barry of 60 Sqn (RFC), when he came up with the ‘revolutionary’ idea of teaching people to fly rather than allowing them to prove it! Widely accepted and quickly adopted, it led to the creation of a series of new and unique RFC Training Depot Stations (TDS). The idea behind these TDSs, was to train new pilots from the initial stage right the way through to gaining their ‘wings’ – all in one single unit; a philosophy that would change the way the Air Force would operate for a very long time.

Initially the two airfields ran independently from each other, Stamford airfield (later RAF Wittering) opened in 1916 operating as a Royal Flying Corps base for No 38 Home Defence Sqn’s anti-Zeppelin unit. It operated both the BE2C and BE12 fighters. The following year in 1917, it changed to the No 1 Training Depot Station (Stamford), then as a result of the formation of the Royal Air Force on 1st April 1918, it was finally re-named RAF Wittering.

RAF Collyweston was located to the western end of Wittering, and opened on 24th September 1917, as No 5 Training Depot Station under the name of Easton-on-the-Hill. It operated a number of training aircraft including: DH6s, Sopwith Camels, RE8s and Avro’s 504. It was also renamed with the formation of the RAF and became known as RAF Collyweston. It continued in the training role until after the war when the squadron was disbanded and the airfield was closed.

Photograph of Wittering airfield looking east, taken 9th May 1944. Collyweston can just be seen at the bottom end of the main runway. (USAAF Photography).

Two years after the outbreak of World War II, Collyweston was re-opened as a grass airfield, a satellite to its rather larger parent station RAF Wittering. By the end of 1944 it would have a total of 4 blister hangars and would be used by a wide range of aircraft.

On May 14th 1940, the first aircraft would arrive, not permanent residents, but a detachment of Spitfire Is of 266 (Rhodesia) Squadron whose main units were based at RAF Wittering. They would stay here only temporarily but return in 1941 for a full month with Spitfire VBs.

Later that month on the 31st of May 1940, the first permanent residents did arrive, Blenheim IFs of 23 Squadron, who would share the night-fighter role with Beaufighters from RAF Wittering. These Beaufighters were using the new and updated AI MK IV radar, a new model that was so heavy and cumbersome, few aircraft could accommodate it. The new radar was introduced in conjunction with Ground Controlled Interception Techniques (CGI) aimed at locating and ‘eliminating’ enemy aircraft at night. The Blenheims – considered too poor for daylight fighter duties – and Beaufighters would prove their worth operating across the Midland and Eastern regions, eventually flying over to the continent later on in the war. After three months of operations from Collyweston, 23 Squadron would completely move across to Wittering leaving Collyweston empty once more.

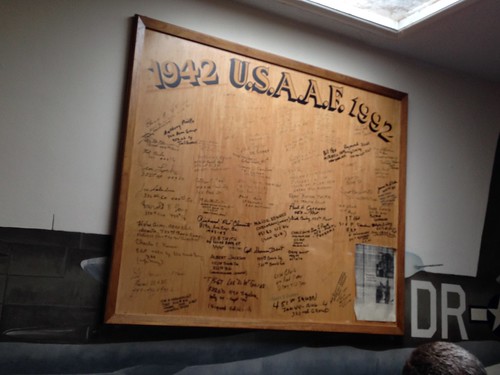

Then on 28th September 1941 the infamous 133 ‘Eagle‘ Squadron manned by American volunteers arrived with their newly acquired Hurricane IIBs. Armed with four potent 20mm canons, they were a force to be reckoned with. This was however, only a short one week stay at Collyweston, and the ‘Eagles’ moved on to RAF Fowlmere leaving their indomitable mark on this quiet Cambridgeshire airfield.

At the end of September 1942, Spitfire VBs of 152 (Hyderabad) Squadron would pass though, staying for three days whilst on their way to Wittering, then North Africa and eventually Malaya. Battle hardened from the Battle of Britain where they had been covering the English Channel and the south coast, they were now non-operational as they began preparing for their move overseas.

Embry (right) was to devise a plan to join RAF Wittering and RAF Collyweston. (Photo Wikipedia)

There then followed a period of change. 288 squadron flying Spitfire VB and IXs would yo-yo around a number of different airfields whilst keeping a detachment at Collyweston. Initially based at Digby, they would be spread over six different airfields (Church Fenton, Duxford, Wittering, Coltishall, Bottisham and Collyweston) creating what must have been a logistical nightmare. The Spitfire would perhaps be their most potent and graceful aircraft which they operated from January to March 1943, before replacing them with Airspeed Oxfords and then Martinets. Moving the main section to Coleby Grange and then Digby, a detachment would remain at Collyweston until the main squadron arrived here in January 1944 – still spread across 6 airfields. In March 1944, 288 Sqn replaced the Martinets with Beaufighter VIs which in turn were replaced with the Vultee Vengence MK IVs in May 1945. After this the squadron moved on and to eventual disbandment in 1946. Throughout their time as an operational unit, they provided anti-aircraft co-operation duties for gunners, flying across the north-eastern regions of England.

It was during 1943 that 349 (Belgium) Squadron would reform at Wittering, with Spitfire VAs. They had previously covered ‘defensive duties’ in North Africa using the American built ‘Tomahawk’ , a role that lasted for a short five month period. In June 1943 they reformed, moved from Wittering to Collyweston and then on to nearby RAF Kings Cliffe.

After concerns were raised by the then Group Captain Basil Embry DSO, DFC, AFC, about the high number of accidents at Wittering, a proposal was put forward, and agreed, to merge the Collyweston and Wittering grass runways. A remarkable feat that was accomplished not by the Ministry but under the direction of Embry himself. By the time the work was completed, Wittering had a much longer 3 mile, well-lit, runway capable of taking crippled heavy bombers. This move was to really signal the end of Collyweston as an airfield in its own right and apart from a short detachment of Austers belonging to 658 Sqn, all major operational activity ceased.

Collyweston would however have one last ‘claim to fame’. The 1426 (Enemy Aircraft) Flight, would operate captured Luftwaffe aircraft in RAF markings. Once new models were found and evaluated, they would be passed on to the flight to be paraded around the country giving ground and flying demonstrations to allied aircrews. Whilst perhaps considered a ‘glamorous’ role, this was fraught with danger, many aircraft crashing with fatal results. On 10th November 1943, Heinkel He111 H-1 ‘1H+EN’ crashed at the Northampton airfield, RAF Polebrook, killing the pilot and four passengers, and injuring four others. 1426 Flight ceased operations at Collyweston on January 17th 1945, being reformed later that year at Tangmere. Some of these Luftwaffe aircraft were later scrapped whilst some like Ju 88 R1 ‘PJ876’, have thankfully found their way into museums such as the Imperial War Museum at Hendon.

With the disbandment of 1426 Flight, Collyweston’s fate had been sealed and it was now officially closed becoming fully absorbed into RAF Wittering.

A captured RAF Messerschmitt Bf 109 (serial number NN 644) with a B-17 Flying Fortress of the 379th Bomb Group at Kimbolton, 8 January 1944. (IWM)

Remnants of Collyweston have all but disappeared. The original site now forms part of what was Wittering’s huge bomb store. No longer used, it has been the venue for many illegal raves, vandalism is rife and the site has been stripped of cabling and other materials. Whilst there are various ‘urban explorer’ videos on You-Tube, it is completely private land and kept behind locked gates. All other traces are well within the boundary and high fences of Wittering airfield, whilst not openly guarded at this point, it still remains an active military site.

Collyweston’s life had been short but notable. A variety of aircraft had graced its runways; it played a major part in the training of crews of the once fledging Royal Air Force, and had been the new home for numerous captured enemy aircraft. A range of multi-national units passed through its gates, either on their way locally or to foreign lands. It fought bravely, competing against its larger more prominent parent station, it was never really likely to survive, but perhaps, and even though Wittering has ceased operational flying activities, the legacy of Collyweston might fight for a little while yet.