At the turn of the last century, flying was in its infancy, and airships formed the main threat from an enemy. Aeroplanes were fragile, slow and cumbersome and those that flew them, risk death at every turn with no means of escape.

As aircraft developed and those in high ranking positions finally saw their potential, production went into overdrive, but there was a greater need, the need for those to fly them.

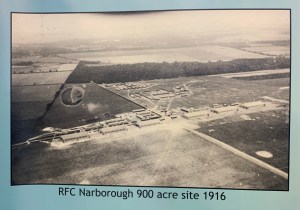

In Norfolk, the threat from airships was very real, and so many new airfields sprung up to defend the British Isles from these roaming menaces. One such airfield, became the largest of them all, a huge site of 900 acres it dwarfed all other aircraft based airfields, and yet, it failed to last beyond the war.

In this part of Trail 7, we head to modern day RAF Marham, for on its fringes lie a field of forgotten heroes who gave their all during the First World War. We look at RAF Narborough.

RAF Narborough

Originally constructed as the largest aircraft base of the First World War, Narborough Airfield in Norfolk has been known by a variety of names over the years: Narborough Aerodrome, RNAS Narborough, RFC Narborough, and later RAF Narborough. However, the most unofficial — and arguably the most evocative — title, ‘The Great Government Aerodrome’, offers a sense not only of its vast scale (spanning over 900 acres), but also of the diversity of aircraft and personnel stationed there. Initially operated by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), the site later came under the control of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), and eventually the newly-formed Royal Air Force (RAF), with each change of name reflecting the evolving structure and ownership of Britain’s early air services.

Records show that the site at Narborough had military links as far back as 1912, in the year that the RFC was established when both the Naval Air Organisation and the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers were combined. Unfortunately, little exists to explain what the site was used for at this time, but it is thought that it was used by the army for training with horses and gun carriages. In later years, it was used as a base from which to counteract the threat from both the German Zeppelin and Schütte-Lanz airships, and also to train future pilots of the RFC and RAF.

Narborough’s history in these early days is therefore sketchy, few specific records exist as to the many changes that were taking place at this time particularly in relation to the development of both the RNAS and the RFC.

However, Narborough’s activities, and its history too, were no doubt influenced on July 1st 1914, when the name RNAS Narborough was officially adopted, and all Naval flying units of the RFC were transferred over to the control of the Navy. A major development in the formation of both forces, there were at this point, a total of: 111 officers, 544 other ranks, seven airships, fifty-five seaplanes (including ship-borne aircraft) and forty aeroplanes in RNAS service.*1 Some of these may well have seen service at Narborough at this point.

Narborough’s first interaction with flying occurred when a solo flyer – thought to have been Lt. F. Hodges in an Avro 504 *2 – touched down on farmland near to Battles’ Farm in the Autumn of 1915. Neither the pilot, the aircraft type nor the purpose of the landing can be substantiated, but it may well have been the precursor to the development of an airfield at this site.

The airfield itself was then developed, opening early that year (1915), on land that lay some 50 feet above sea level. It sat nestled between the towns of Kings Lynn (10 miles), Swaffham (5 miles); and Downham Market (9 miles), and a mile or so away from the small village of Narborough. A smaller aerodrome would, in 1916, open literally across the road from here, and at 80 acres, it would be tiny in comparison. However, over time, it would grow immensely to become what is today’s RAF Marham, an active airfield that has matured into one of the RAF’s top fighter airfields in the UK.

So by mid 1915, Narborough’s future had been decided, designated as a satellite station to RNAS Great Yarmouth, (itself commissioned in 1913) it was initially to be used as a night landing ground for those aircraft involved in attacks on enemy airships, the most likely reason for its location. No crews were permanently stationed here at the time however, ‘on-duty’ crews later being flown in to await the call to arms should an airship raid take place over East Anglia.

This first arrival of an aircraft in August 1915, led to the site being kept in use by the RNAS for the next ten months. During that time, aircraft of the Air Service would patrol the coastline around Norfolk, using aircraft mainly from Great Yarmouth along with a series of emergency landing grounds including Narborough. The threat from German airships at this time being very real. These landing grounds were strategically placed at intervals along the coastline with others more inland, these included: Aldeborough, Burgh Castle; Covehithe; Holt and Sedgeford all of which combined to make North Norfolk one of the densest regions for airfields at that time. But, and even with all these patrols, the roaming airships that made their way across the region had little to worry about as many of the fighter aircraft used could neither reach them at the higher altitudes nor locate them in poorer weather.

However, as a night landing ground, little activity would directly take place at Narborough (there are no recordings of airship sightings from Aircraft using the airfield) and so after a dormant ten months, the RNAS decided it was surplus to requirements and they pulled out leaving Pulham the only ‘in-land’ station larger than Narborough open in Norfolk at that time.

The future of Narborough could have so easily ended there, but even as closure plans were made, its future was still relatively secure, and it would not be long before a new user of the site would be found. Discussions were already in hand for the RFC to take over, provided the land owners’ permitted it! Luckily they did, and soon fifty acres of rough terrain and a small number of canvas flight sheds were theirs. As for staff accommodation, there was none, so when 35 Sqn arrived at the end of May 1916, Bell tents and make shift accommodation had to be erected by the personnel, in order to protect themselves from the harsh Norfolk elements.

With the First World War raging across the fields of Flanders, the demand for aircraft and trained crews grew rapidly. These new flying machines were evolving swiftly into lethal weapons and highly effective reconnaissance platforms, capable of identifying enemy positions and directing artillery fire with increasing accuracy. To meet the urgent need for trained airmen, hurried training programmes were established, and Narborough soon became a vital preparation ground for budding pilots.

Training, by any standard, was rudimentary. Recruits were required to pass a series of written examinations, followed by up to twenty hours of solo flying, a number of cross-country flights, and two successful landings. Added to this was a fifteen-minute flight at 8,000 feet, culminating in a dead-stick landing — that is, returning safely to earth with the engine cut. It was, in truth, barely enough experience for what lay ahead in the violence of aerial combat.

Like many newly established stations, Narborough was designated as an RFC training site — officially known as a Training Depot Station — joining a growing network of such facilities across Norfolk, Suffolk, and Lincolnshire. Their primary role was to prepare pilots for the rigours of air combat, with instruction in dog-fighting, aerobatics, cross-country navigation, and formation flying.

With the arrival of the RFC came immediate expansion. Additional acreage was acquired that same year, extending the airfield westward beyond the area already occupied by the RNAS, bringing it close to the present-day boundary of RAF Marham. As was often the case with wartime construction, adjustments to the local infrastructure were necessary. A road that once bisected the site was eventually closed to accommodate the growing airfield footprint.

So, it was during June 1916 that the first RFC squadron would make use of Narborough as an airfield, 35 Sqn transferring over here from Thetford with Vickers FB.5 and FE.2bs. disposing of their D.H.2s and Henry Farman F.20s in the process. Within two months of their arrival, the nucleus of the squadron would then be used to form a new unit, 59 Sqn, who were also to be stationed here at Narborough (under the initial temporary command of Lieutenant A.C. Horsburgh) with RE8s. On the 16th August, Horsburgh would take on a new role when the new permanent commander Major R. Egerton, was transferred in. It would be he who would take the unit to France the following year and command until his death in December 1917.

During their time here, these daring young trainees, many whom were considered dashing heroes by the awe-inspired locals, would display their skills for all who lined the local roads to see. As these eager young men quickly learned though, flying was not always ‘fun’, and the dangers of the craft were always present, many with dire consequences. Accident rates were high and survival from a crash was rare, even ‘minor’ accidents could prove fatal. All Saints church yard at Narborough, pays testament to their dangerous career with fourteen of the eighteen military graves present being RFC/RAF related.

The initial drive for both these squadrons was to train pilots in the art of cavalry support, using advanced pilot training techniques. This included being able to send Morse code messages at a rate of six words per minute*2 whilst flying the aircraft over enemy territory – certainly no mean feat.

Deaths on and off the airfield were commonplace and not all aviation related either. During late June 1916, one of the Air Mechanics of 59 Sqn, Charles Gardner, suffered a heart attack and died, just one day prior to the official formation of his squadron. Whilst not considered to have been directly related to his role, his loss saw the beginning of a string of deaths in August that would set the scene for the coming months.

The first of these was another thought to be, unrelated aviation death, although whether or not Corporal Patrick Quinn was on duty at the time is unclear. He died on August 18th, whilst riding his motorcycle in the vicinity of the airfield, the narrow Norfolk roads catching him unaware. Then, just two days later on August 20th, the first of many fatal air accidents would occur.

In this instance, one of 59 Sqn’s pilots, Lt. Gordon William Hall, was killed when the DH.1 (4631) he was flying, side-slipped on approach to the airfield crashing into the ground as a result. A Court of Inquiry (87/8413) concluded that the aircraft had been “banked too steeply” and that the pilot had put the aircraft into a dive that made it uncontrollable. A verdict therefore of ‘accidental death‘ was subsequently recorded against Lt. Hall.*3

A mere eight days later, it was the turn of 35 Sqn to suffer its first fatality and in a not too dissimilar accident. On the 29th, an Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 (6201), was written off after it too side-slipped and dived following a slow turn. The Pilot, Air Mechanic 1st Class Moses Boyd, was tragically killed in the accident flying an aircraft that was based at Thetford but undertaking a training exercise here at Narborough. His Court of Inquiry (Ref. 87/4971) on 9th September 1916)*3 , summated that it was a “Flying accident. Turning having lost flying speed”. By now, the dangers of flying were becoming all too apparent and with another two deaths before Christmas, the glamour of flying was quickly becoming tarnished.

However, despite these accidents, young men continued to arrive at the airfield for training, but the large influx of personnel did not mean it was at all a glamorous place to be.

As a training ground, accommodation was basic to say the least, Narborough being described by one trainee as a “desolate, God-forsaken place“*4. Quickly realising the problem, the authorities, began to erect new buildings not only for personnel accommodation, but for training and maintenance roles as well. In response, a total of six permanent hangars, probably RFC General Service Flight Sheds, were erected by the design company and builders Boulton & Paul, three each side of the main road. The Boulton & Paul company based at Norwich, would go on to design and build many aviation related products including the famous ‘Defiant’, a turreted fighter of World War II.

With continued expansion over the next two years, up to 150 buildings would eventually be built on the site, a mix of technical, administrative and accommodation. This on going process of construction and development would, by the end of the war, see some 1,000 personnel based here at Narborough – a number comparable with many modest Second World War airfields.

Narborough wasn’t the only airfield being developed in the immediate area though. Next door, across the road, the new RFC Marham was opening, a much smaller site, that sat in the centre of what is now modern day RAF Marham. Why the two were put so close together is anyone’s guess, but Marham quickly became the home and headquarters to ‘C’ Flight 51 Squadron. The remaining two flights of the squadron being based at both RFC Mattishall and RFC Tydd St Mary.

Marham opened for business in September 1916 and one of those who would be stationed here was Major A.T. Harris, later ‘Bomber Harris’ of Bomber Command fame. He was in command of 191 Night Training Squadron, and took part in many flights from the airfield. Marham, like Narborough, would eventually close at the end of the war in the huge disarmament programme of the immediate post war years. But, unlike Narborough, it would be reborn in the expansion period of the 1930s and grow to what it is today.

There was a good relationship between the two stations, with plenty of rivalry and good humour. Flour bombs from Marham crews on Armistice day were met with a retaliation from Narborough crews with soot bombs, the culmination of several years of war finally coming to an emotional close.

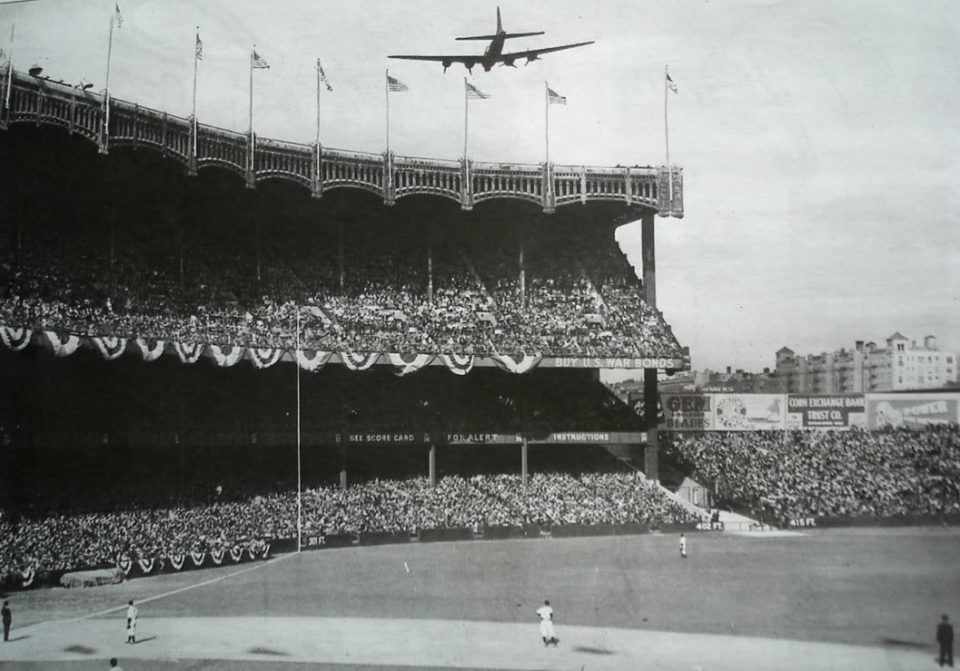

RFC Narborough 1916. The six RFC hangars can be seen in line along the former Narborough – Beachamwell Road. (Marham Aviation Heritage Centre)

The RFC was now building in strength, not only in its front line units but in its reserves too. On November 2nd, 1916 a new reserve squadron was constituted and formed here at Narborough, 48 (Reserve) Squadron (RS). Models flown by the unit at this time included the Grahame White XV, the Maurice Farman Shorthorn and Sopwith’s Pup. As a newly formed unit they would have to get established, gain crews, admin staff and equipment. Once this was in place they could then move on, and after just a month, they departed Narborough heading for the Lincolnshire airfield at Waddington.

The vacancy at Narborough was quickly filled though, in mid December No. 50 Reserve Squadron (RS) arrived from the Kent village of Wye, just as the Sedgeford based 53 Reserve Squadron (RS) also arrived with 504s, BE2s, DH6s and RE8s.*5

Between their arrival and November the following year (1917), the date they departed for Spitalgate, 50 Reserve Squadron would lose twelve flyers in accidents, three Air Mechanics with the remainders being Lieutenants, both 1st and 2nd Class. Five of these remain in the local churchyard.

In early 1917, Nottingham born Captain Albert Ball, VC, DSO & Two Bars, MC arrived at Narborough; a veteran of the front line, he served here for only a short time as an instructor before the draw of the front line took him back once again. This time there was no coming home as he was killed after an intense aerial battle on May 7th that year with 44 victories under his belt. He was just 20 years of age.

With increasing numbers of squadrons and men being required for front line units in France, both the original 35 and 59 Squadrons departed Narborough in early 1917. 35 Squadron were first to go, and those left behind saw them off from local train stations with all the pomp and ceremony they could muster. A few days later a convoy of 3 ton Leyland lorries, trailers and an assortment of other vehicles loaded with men and equipment, set off for France where they met the air party who had already flown to St. Omer. 59 Squadron would follow to the same airfield on February 23rd, both squadrons remaining in France until 1919 and the war’s end.

In Part 2, the reserves are left to carry on training, but its not an easy job. The development and growth of Narborough continues and eventually the RAF is formed. There are major changes all round.

The full story of Narborough can be read in Trail 7 – North West Norfolk.