In Trail 33, we continue to explore the county of Essex. Touching the outskirts of London to the south and Suffolk to the north, it has an aviation history that has lasted over two world wars.

After visiting both Matching Green and Andrews Field, we travel a few miles west back again toward Stansted Airport.

Our next stop is Great Dunmow.

RAF Great Dunmow (Station 164)

Great Dunmow is another former airfield that sits in the shadow of nearby Stansted airport, itself a former World War 2 airfield. Dunmow was home to only two RAF units, 190 Squadron (RAF) and 620 Squadron (RAF) operating Stirling IVs and latterly the Halifax III and VII. It was also used by the USAAF flying B26 Marauders under the 386th BG.

Great Dunmow, had a multitude of names: Little Easton, Easton Lodge and Great Easton due to its close proximity to all three locations. It was designated Station 164 by the Americans but became more commonly known as Great Dunmow.

Not built until mid-way through the war (1942-43) by the US Army’s 818th Engineer Battalion (Aviation), the American units of the 386thBG were the first to move in.

It would have three runways (concrete and wood chip), with the main one running north-west / south-east and 6,000ft in length. The second and third runways ran east-west and north-east \ south-west and were both 4,200 ft in length. The main technical and administrative areas were to the north side in which one of the airfield’s two T2 hangars were located. A bomb store was situated to the east and was capable of storing in excess of 800 tons of bombs. Dispersals consisted of 50 loop style hardstands around the concrete perimeter track. The staff accommodation sites were dispersed over 12 sites all to the north around the Easton Lodge, referred to by crews as ‘The Big House’*1. Two Mess sites, two WAAF sites, a sick quarters, an officers and four airmen sites housed a huge number of personnel – even parts of the house itself were used. A communal site provided a number of small shops selling local produce and groceries.

The secondary runway (N/E-S/W) disappears into the distance. This section is the only part in full width. The tree line marks the third E-W runway.

The 386th BG (M) were activated mid-war, on December 1st 1942 at MacDill Field, Florida, and arrived in England with their olive and grey B-26s in the following June. Their journey to Great Dunmow would take them via both RAF Snetterton Heath and RAF Boxted. For four months they would operate under the control of the Eighth Air Force, swapping in October 1943, to the 99th Combat Wing of the Ninth Air Force. Consisting of four Medium Bomb Squadrons: 552nd (code RG), 553rd (AN), 554th (RU) and 555th (YA), they would focus their attention on airfields, marshalling yards and gun batteries. Over the winter of 1943-44 they targeted V weapon sites, along France’s coast, and attacked enemy airfields during the ‘Big-Week’ campaign of February 1944.

During the Normandy invasion, they targeted bridges and Luftwaffe airfields, coastal batteries, fuel and munitions supplies, they preceded the allied forces as they moved inland; supported ground troops at Caen and St. Lo in July 1944, earning themselves a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) for their actions. As the allies moved deeper into France, they were then free to move to the continent allowing them to reach further afield and support the advance toward and into Germany itself.

B-26 Marauder ‘AN-J’, (s/n 41-31585) nicknamed “Blazing Heat” of the 553rd BS, 386th BG, 23rd June 1944. balances on its nose after making a crash landing at Great Dunmow. (IWM)

In total, the 386th would fly 257 missions from Dunmow, operating between 24th September 1943 and 2nd October 1944, in an aircraft that earned itself a rather distasteful name for being unreliable and difficult to fly. Later versions having both larger wingspans and flying surfaces, partly cured this problem, but in the hands of a good crew, they were deemed no more ‘dangerous’ than any other bomber of that time. In fact, a number of Marauders were known to return home in an incredible condition, after taking a substantial beating at the hands of both flak and fighter attention.

After the 386th left Dunmow, it was handed over to the RAF and the first unit to arrive was 190 Squadron (RAF) with the Stirling IV. Pulled out of bomber squadrons for its ‘poor’ record, they were used by various units for both mine laying activities and glider-tug operations. Arriving from Fairford they stayed here until July 1946 whereupon 190 Sqn was disbanded. During this time they also flew the Halifax III and later the Halifax VII – an aircraft that was proven in combat and also as a transport machine. With a history that extended back to the First World War, 190 Sqn operated as a Glider-tug unit taking Horsa gliders to a number of prestige targets; both Normandy, during the D-Day invasion, and Arnhem during the ill-fated Rhine crossing of Operation Market Garden. They flew fuel and supplies to advancing troops and carried out a number of transport duties as the war drew to a close.

The changeover between the exiting Americans and the arriving British was seen as an ideal opportunity to gather ‘supplies’ by the locals. Many tins of rationed food and other ‘luxuries’ left by the U.S. airmen were deemed ‘fair-game’ and ‘removed’ in the intervening days. Dennis Williams*2 book ‘Stirlings in Action with the Airborne Forces’ describes in detail how the incoming airmen were surprised by the extent of the items left by the Americans.

Four days after 190’s arrival, 620 Sqn also arrived at Dunmow, along with all their respective Echelons. Like their partners, they also came from RAF Fairford flying the Stirling IV. A former bomber squadron, they cut their teeth at RAF Chedburgh, then in November 1943 they transferred across to the Airborne Forces. Also flying glider operations, they too swapped their Stirlings for Halifax A.VIIs in July 1945 before moving off to the Middle East post war. Similarly, 620 Sqn flew troops into some of the most dangerous war zones, losing a number of crews and aircraft along the way.

Both 620 and 190 Sqn returned to operations soon after their arrival, flying SOE operations, glider training sorties across the UK and dropping equipment into occupied territory. As can be imagined these dangerous operations were not without their problems. A number of aircraft were lost and even during training flights, losses were still incurred.

On the 21st November 1944, Stirling LK276 crashed killing all seven crew members. It was initially thought that the pilot either failed to read his altimeter correctly causing the aircraft to strike trees and power lines, or he took his attention away from the instruments in front. Subsequent reports however, show eye witnesses claiming to have seen a following night fighter. Again contradictions in statements were not helpful and no conclusive decision could be reached. The court of enquiry ruled that it was an accident and so the case was closed. Whatever the cause was, it was a major blow to the crews at Great Dunmow.

The Administrative site is now used by the local farmer and small ‘industrial’ units. The crew briefing room (front) stands in front of the intelligence block. The main Operations block has gone but the station offices are still here.

Being so far south, Great Dunmow offered a safe haven for some returning bombers. On November 5th 1944, whilst on their return from mission 166 over Frankfurt, the 401st were diverted to the Great Dunmow as bad weather had closed in over Deenethorpe. An eye-witness account describes two B-17s ‘colliding’ on the runway, whilst other records suggest the two B-17s crash landed both suffering from extensive flak damage. Records show one of them as B-17G ’42-102674′ flown by 2nd Lt. William F. Grimm and the other as B-17 ’42-31662′ flown by 1st Lt. Leland R. Hayes. However this particular aircraft (42-31662) was known to be ‘Fancy Nancy IV‘ flown by Walter Cox which did not crash at Dunmow, going on to serve to the war’s end. As with many war records, it can be difficult ascertain total accuracy and an anomaly has occurred here somewhere.*3

Both 190 and 620 Sqns continued on in SOE operations, including their first to Norway on the night of November 6th/7th 1944. Both operations were seen as failures but it would highlight the difficulties of flying for four hours to often heavily fog-laden environments and back again.

Poor weather dogged this part of the country especially in the early 1940s. The airfield was in a poor condition and a great deal of work had to be carried out to assist operations. Lighting, repairs to the runways and drainage were all severe problems and all needed urgent and immediate attention. Conditions therefore were not good. Successive cold winters and the continual mud, left some with very ‘unsavoury’ memories. Working in bitter cold weather outside certainly became a challenge for hard pressed ground-crews.

A number of operations involved Dunmow aircraft over the next few months, but they were mainly confined to practice flights towing Horsa gliders. Then in late March 1945, Operation ‘Varsity’ began. The drive into Germany required 21,000 troops, 1,800 transport aircraft and over 1,300 gliders. The base was sealed off from the outside world, only air-tests and spoof flights were scheduled, and then on the morning of the 24th March 1945 60 aircraft were lined up along the runways ready to go.

Anti-aircraft fire was heavy and conditions poor over the drop zone, but all 190 Sqn and 620 Sqn aircraft returned – some with damage. They seem to fair far better than the gliders though of which some 80% were damaged by flak – many severely.

Toward the end of the war, both squadrons dropped supplies and recovered POWs from the now free Europe. It was an emotional time for all but accidents and losses still occurred and crews still died.

In July 1945 620 Sqn received the Halifax A.VII and finally in January 1946 it would be all change for Great Dunmow. 620 Sqn were posted to Aqir in Palestine; 190 Squadron was disbanded and the unit renumbered as 295 Squadron and sent to Tarrant Rushton – this was the end for Great Dunmow. The airfield was used as a vehicle storage unit until 1948, at which point it was closed for good. The tower and major buildings were demolished, the concrete dug up for hardcore for the new road, and the remainder returned to agriculture, a state it survives in today.

As with many airfields today, there is little left to see in the way of buildings and infrastructure at Dunmow airfield. A memorial stands alongside the B1256 road a few miles to the south side of the airfield site and an adjacent footpath takes you through what was the bomb store on to the airfield itself. By driving from here to the village of Little Easton, you can more easily access the site from the northern side, by far the better option. Drive through the small village of little Easton, past the quaint village duck pond and on toward Little Easton Manor. Much of the grounds of the Manor were the accommodation areas and now as an estate once more, is (at the time of writing) up for sale for a cool £5,000,000.

Before arriving at the manor – which shows little of its aviation history – there is a small tourist sign and access to the adjacent fields. Stop here. The footpath to your left crosses the airfield utilising much of the remaining perimeter track. This path is an old access road to the airfield and takes you up to the threshold of the former second runway (N/E-S/W). It is a short walk but once there the full width of the runway can be seen, and when looking on, so to can the length (albeit cut short). The only part that is full width, the enormity of these tracks is staggering. The path then leads off to the west through the field strangely enough only feet from the usable but broken and much narrower perimeter track. At the end of this path, you arrive at the threshold of the third (E-W) runway. Now only a single farm track; the length is in its entirety but again standing at this point you can see how long the runways were. The path then crosses over the southern half of the airfield away to the south but there is little to be gained from taking this route, other than to know you have walked where many crews would have spent their time. The dispersals that once stood here are now long gone and no trace remains of their existence.

If you continue east the path splits again and the one turning south takes you through the former bomb store and onto the afore-mentioned memorial. Now a quarry, the store is supplied by the perimeter track which is used by lorries to transport materials. Turning back on yourself it is possible to walk along the perimeter track back to your starting point. Along these paths are signs of the concrete that once carried the B-26s, Stirlings and Halifaxes, much narrower now, their significance little more than a farm track. Away to your right, was the former ‘dump’ or Marauder graveyard, where scrapped B-26s were left to rot.

Return to the road and walk from here west toward the lodge. After a few minutes you arrive at the former airfield entrance. The airfield sub-station marks the entrance and a footpath takes you along the road onto the airfield site. The technical area would be to your left and right, with one of the T2 hangars to your left. Follow the path as it crosses the field and you arrive where the tower once stood. There is no sign of it now, but the path takes you right though the spot where so many decisions were made and aircraft counted back. The path then leads on through the airfield and joins the third (E-W) runway at its centre. largely overgrown with trees, the line is clearly evident, but again evidence of the concrete structure lay scattered along the edges of this once gigantic pathway.

Turn back again and through the technical area. Hovering over the tress to your left you will be able to see the current control tower and landing aircraft at Stansted airport – a mere stones throw away. Also to your left are a small group of farm buildings , amongst them a blister hangar that appears to have been moved here after the war. Beyond these and accessible from the roadway, a small collection of administrative buildings remain now used by the local farmer and as small industrial units. By walking along the road these are accessible and perfectly visible from the roadway.

The road from here continues on and takes you into where the main accommodation sites once stood. Much of this is private land but traversed in places by small bridal ways and footpaths. Immediately opposite was the mess site 4 and further along the road the sick quarters. The remaining accommodation sites were to the north of here amongst the now dense forests that have replaced them. To the north of these woods was the sewage plant that once served the airfield. It has now been replaced by a more a modern unit but its location is still precise. Various tracks lead into private land from here, but they are the original tracks for the various accommodation sites that once housed the crews and staff of this once busy base.

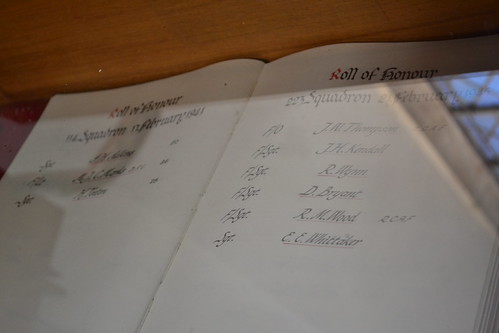

Return to your car and drive back to Little Easton stopping at the church (St. Mary the Virgin). Inside at the back of the church on the north wall are two beautiful widows that commemorate the service of those stationed here at Great Dunmow – both RAF and USAAF. Primarily focusing on the USAAF, they depict a number of scenes – each reflecting the daily lives of the airmen. Some show them holding hands with the civilian children, others preparing for and returning from flight; Marauders in the ‘Missing man’ formation, and two hands clasped together as a sign of American and British unity – each one is beautifully presented and well maintained. One of the windows depicts ‘peace and tranquillity’, whilst the other called “The Window of the Crusaders”; depicts the role played by the 386th. Plaques, rolls of honour and information boards give great detail about the lives of those who were stationed here for those short periods during the Second World War.

Great Dunmow served an important role during the Second World War. Today its historical significance is in no way played down. Whilst the majority of the airfield is now crops, ‘free access’ allows you to revisit those days of the Second World War, to walk in the footsteps of heroes, to experience the sight of a welcome runway as a returning bomber would. The huts and church windows stand as reminders of those who, whilst so young, gave their all in the name of freedom and democracy.

Notes and further reading

*1The Big House, was the former Estate of Frances, Countess of Warwick, who was regularly visited by the Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII. A railway halt was built outside the house to accommodate these visits.

*2 Williams Dennis, Stirlings in Action with the Airborne Forces, Pen and Sword Aviation, 2008 – this book provides an in-depth look at life within both 620 Squadron and 190 Squadron whilst at RAF Great Dunmow. It is highly recommended as a follow-up to the activities of these two units whilst here and abroad.

*3 See the 401st BG website for details of these aircraft and missions, including the original mission reports.