We continue, in Trail 44, looking at the life of Sir Barnes Wallis, a man known for his expertise in engineering and design. Following on from his early works in airship design, we now turn to his Second World War and post war work.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, new designs of aircraft and weapons were much-needed. Wallis’s geodesic design, as used in the R100, had been noticed by another Vickers designer Rex Pierson, who arranged for Wallis to transfer to Weybridge, where they formed a new team – Pierson working on the general design of the aircraft with Wallis designing the internal structures. This was a team that produced a number of notable designs including both the Wellesley and the Wellington; both of which utilised Wallis’s geodetic design in both the fuselage and wing construction.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, new designs of aircraft and weapons were much-needed. Wallis’s geodesic design, as used in the R100, had been noticed by another Vickers designer Rex Pierson, who arranged for Wallis to transfer to Weybridge, where they formed a new team – Pierson working on the general design of the aircraft with Wallis designing the internal structures. This was a team that produced a number of notable designs including both the Wellesley and the Wellington; both of which utilised Wallis’s geodetic design in both the fuselage and wing construction.

What made Wallis’s idea so revolutionary was that the design made the air frame both light-weight and strong, and by having the bearers as part of the skin, it left more room inside the structure thus allowing for more fuel or ‘cargo’. An idea that helped provide greater gas storage for the R100.

Whilst both the Wellesley and the Wellington went on to be successful in the early stages of the war (11,400 Wellingtons saw service), they were both withdrawn from front line service by the mid war years, being replaced by more modern and advanced aircraft that could fly further and carry much larger payloads.

Saddened by the rising death toll, Wallis put many of his efforts into shortening the war. His idea was that if you attack and destroy the heart of production, then your enemy would have nothing to fight with; in this case, its power supply. To this end he started investigating the idea of breaching the dams of the Ruhr.

Wallis’s idea was to place an explosive device against the wall of the dam, thus utilising the water’s own pressure to fracture and break open the dam. Conventional bombing was not suitable as it was too difficult to place a large bomb accurately and sufficiently close enough to the dam to cause any significant damage. His idea, he said, was “childishly simple”.

Using the idea that spherical objects bounce across water, like stones thrown from a beach, he determined that a bomb could be skimmed across the reservoir over torpedo nets and strike the dam. A backward spin, induced by a motor in the aircraft’s fuselage, would force the bomb to keep to the dam wall where a detonator would explode the bomb at a predetermined depth, similar in fashion to a naval depth charge. The idea was simple in practical terms, ‘skip shot’ being used with great success by sailors in Nelson’s navy; but it was going to be a long haul, to not only build such a weapon, the aircraft to drop it, nor train the expert crews to fly the aircraft; but to simply convince the Ministry of Aircraft Production that it was in fact feasible.

Wallis began performing a number of tests, first at his home using marbles and baths, then at Chesil Beach in Dorset. Both the Navy and the Ministry were interested when shown a film of the bomb in action, each wanting it for their own specific target; the Navy for the Tirpitz, and the Ministry for the dams. Wallis still determined to use it on the dams, carried out two projects side-by-side, “Upkeep” for the dams, and “Highball” for the Navy*3.

“Upkeep” was initially spherical, and the first drop from a modified Lancaster took place in April 1943 at Reculver near to Herne Bay, where this statue is located. He persevered with aircraft heights, speeds and bomb design modifications, carefully honing them until on April 29th 1943, only three weeks before the actual attack, the bomb finally worked for the first time.

Wallis’s plan could now be put into action, and with a new squadron of the RAF’s elite bomber crews put in place, the stage was set and the dams of Ruhr Valley would be the target.

The attack on the dams have become legendary, and of the 19 aircraft of 617 Squadron that took off that May evening in 1943, only 11 returned, some after sustaining considerable damage. Operation Chastise saw two of the three dams, the Mohne and Eder, successfully breached and the third, the Sorpe, severely damaged forcing the Germans to partially drain it for safety.

The names of the crews of 617 Squadron at RAF Scampton. Those with poppies next to them, did not return.

Following the success of Operation Chastise, Wallis went on to develop other bombs capable of devastating results. His initial plan, a Ten ton (22,000lb) bomb, had to be scaled back to 12,000lb as there was no aircraft capable of dropping it at that time. Codenamed ‘Tallboy’, it would be a deep penetration bomb 21 feet in length with a hardened steel case and 4 inches of steel in the nose. The bomb contained 5200lbs of high explosive Torpex (similar to that used in the Kennedy Aphrodite mission) and would have a terminal velocity of around 750 miles per hour.

The idea of Tallboy, was to create a deep underground crater into which structures would either fall or be rendered irreparable. With a time fuse that could be set to sixty minutes after release, it was used on strategic targets such as the Samur Railway Tunnel in France, rendering the tunnel useless as it had to be closed for a considerable amount of time.

The crater made by Barnes Wallis’s Tallboy bomb above the Samur Railway Tunnel, 9th June 1944. *4

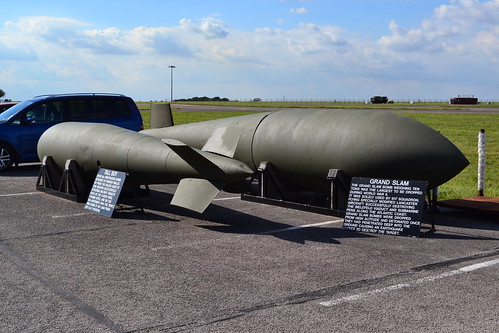

Soon after this, Wallis began developing his Ten Ton bomb, the “Grand Slam”, a mighty 26ft in length, it weighed 22,000lb, and would impact the ground at near supersonic speeds. Wallis’s design was such that the bomb could penetrate through 20 feet of solid concrete or 130 feet of earth, where it would explode creating a mini earthquake. It was this earthquake that would rock the foundations of buildings and structures, or simply suck them into a crater of massive proportions*5.

Production of the Grand Slam was slow though. It took two days for the casting to cool and then after machining, it took a further month for the molten Torpex to set and cool. The first use of the Grand Slam occurred on 14th March 1945 against the Bielefeld Viaduct in Germany, on which one Grand Slam and 27 Tallboys were dropped. Unsurprisingly, the viaduct collapsed and the railway was put out of action.

Wallis had created more exceptionally devastating weapons, they were so successful that 854 Tallboys and 41 Grand Slams were dropped by the war’s end.

Post war, Wallis carried on with his design and investigations into aerodynamics and flight. He was convinced that achieving supersonic flight with the greatest economy was the way forward, and in particular variable geometry wings. The government was keen to catch up with the U.S., awarding Vickers £500,000 to carry out research into supersonic flight. Wallis’s project received some of this money, and he researched unmanned supersonic flight in the form of surface-to-air missiles. Codenamed ‘Wild Goose‘ (later ‘Green Lizard’) the project ran to 1954 when it was terminated.

Wallis continued with his research into swing wing designs, his first being the JC9, a single seat aircraft 46 feet in length. It was produced but never completed and was scrapped before it ever got off the ground. Wallis wasn’t put off though, and he continued on developing the ‘Swallow’, a swing wing aircraft that could reach speeds of Mach 2.5 in model wind tunnel investigations.

In its bomber form it would have been equivalent in size to the American B-1, with a crew of 4 or 5, and a cruising speed of Mach 2. It would have a range of 5,000 miles whilst carrying a single Red Beard nuclear bomb.

Whilst not selected to meet the R.A.F.’s OR.330 (Operational Requirement 330), which was eventually awarded to TSR.2, they were interested enough for him to proceed until the 1957 Defence White Paper put an end to the project, and it was cancelled.

Looking for funding Wallis turned to the U.S. hoping they would grant him sufficient funds to continue his work. After many meetings between Wallis and the U.S American Mutual Weapons Development Program at NASA’s Langley research facility, he came away disappointed and saddened that the Americans used his ideas without granting him any funding.

American research continued, eventually developing into the successful General Dynamics F-111 ‘Aardvark’, the world’s first production swing-wing combat aircraft.

Wallis continued with other supersonic and hypersonic investigations; designs were drawn up for an aircraft capable of Mach 4-5, using a series of variable winglets to link subsonic, supersonic and hypersonic flights, many however, never went beyond the drawing board.

Wallis didn’t stop there, he continued with many great inspirational projects: the Stratosphere Chamber, a test chamber where by simulated impacts on aircraft travelling at 70,000 feet could be safely tested and analysed; the Parkes Telescope, a radio telescope in New South Wales; the Momentum Bomb, a nuclear bomb designed to be released at low-level and high-speed, enabling the release aircraft to escape the blast safely, and in the 1960s, a High Pressure Submarine designed to dive deeply beyond the range of current detection.

In recognition of his work, Wallis was knighted in 1968, and he was also made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society.

Wallis, after working beyond his forced retirement, died at the age of 83, on 30th October 1979, in Effingham, Surrey. He is buried in the local church, St Lawrence’s Church, in Effingham, a village he contributed greatly to. He was the church secretary for eight years, and an Effingham Parish Councillor, serving as Chairman for 10 years. He was also the Chairman of the Local Housing Association, which helped the poor and elderly of the village to find or build homes; and as a fanatical cricketer, he was Chairman of the KGV Management Committee who negotiated the landscaping of the “bowl” cricket ground, so good was the surface, it was used as a substitute for the Oval in London.

There are numerous memorials and dedications around the country to Wallis, and there is no doubt that he was both an incredible engineer and inventor who made a major contribution to not only the war, but British and world aviation in general.

His statue at Herne Bay overlooks Reculver where the first “Upkeep” bomb was dropped by a Lancaster bomber during the Second World War, and it is a fine tribute to this remarkable man on this trail.

Sir Barnes Neville Wallis.

From here, we continue to travel east, toward the coastal town of Margate. A few miles away is the now closed Manston airport, formerly RAF Manston, an airfield that is rich in History, and one that closed causing such ill feeling amongst many.

Sources and further reading

*3 The Mail online published a report on the discovery of a Highball bomb found in Loch Striven, Scotland in July 2017.

*4 Photo © IWM (CL 4322)

*5 The Independent news website– “Secrets of the devastation caused by Grand Slam, the largest WWII bomb ever tested in the UK.” Published 22/1/14

The Barnes Wallis Foundation website has a great deal of information, pictures and clips of Barnes Wallis.

A list of memorials, current examples of both Upkeep and Highball bombs, and displays of material linked to Barnes Wallis, is available through the Sir Barnes Wallis (unofficial) website.