After Part 1 and Part 2 of the trail, we find that Debden has a new owner, the USAAF. Its fortunes change and it becomes home to one of the most famous Fighter Groups of the Second World War.

121 Sqn, were reformed in 1941 at Kirton-in-Lindsey, initially with the Hurricane MK. I, and then IIBs moving on to the Spitfire IIA and eventually the VB; a model they brought with them to Debden. 71 Squadron had been formed at Church Fenton, and after moving through a series of stations that included Martlesham Heath, they arrived at Debden on 3rd May 1942 also with the Spitfire VB. On September 29th 1942 the two RAF units along a with a third, the 133 Sqn at Great Sampford, were officially disbanded, but the men of the three units were not dispersed. Instead they absorbed into the USAAF as the 4th Fighter Group (FG). The men of these squadrons were all originally US volunteers who formed the three American ‘Eagle Squadrons‘ operating within the Royal Air Force.

The 4th FG was specially created to take these three squadrons, they were brought together at Debden where they became the 334th (71 Sqn), 335th (121 Sqn) and 336th (133 Sqn) Fighter Squadrons (FS). Debden would then be passed from the RAF to the USAAF, the transition of which, would be smooth and relatively uneventful, the units retaining the Spitfires they already had before replacing them with P-47s later in 1943.

A Spitfire Mk. V (QP-V) of the 334th Fighter Squadron, 4th Fighter Group. (IWM)

The handover of ownership of Debden took place on the 12th September 1942, with an official ceremony on the 29th to coincide with the disbandment of the RAF units. During this ceremony both Major General Spatz and Brigadier General Hunter were joined by Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas of the RAF’s Fighter Command, to see Debden and the aircrews officially joining the ranks of the USAAF. Initially little changed after the handover, the most prominent feature being the removal of the RAF roundels and the application of the US Star on the aircraft’s fuselage and wings. New ground crews were brought in and trained by RAF personnel to maintain the Spitfires, and so RAF crews remained on site until such times as the American were in position to become self-sufficient.

As these crews had been involved in front line operations for some time – the 71st having gathered a total of over half the 73.5 kills recorded by the three squadrons – they were immediately made operational and went on performing in the duties they had been so adept at completing thus far. So proud of their origins were they, that the 4th FG stood out from their fellow Americans both in the way they flew, and the way they behaved.

With their first mission under the ‘Stars and Stripes’ on October 2nd, they would not have to wait long before seeing action once again. The Eagle Squadrons would become famous throughout the war, achieving many records in aerial combat over the next three years. Taking part in the Normandy invasion, aerial battles over Northern France, the Ardennes, the Rhineland, and over Berlin itself; they would not be short of combat experience. Throughout their time the 4th FG would achieve many ‘firsts’. They were the oldest fighter group of the Eighth Air Force, and their combined totals of enemy aircraft destroyed both in the air and on the ground was the highest of the entire USAAF. They were also the top scoring Allied Fighter Group of the war, destroying 1016 enemy aircraft for a loss of 241 of their own aircraft, many of which were due to flak. They would be the first unit to engage the enemy in air battles over both Paris and Berlin, and they would be the first US Eighth AF Group to penetrate German airspace – a record they established on 28th July 1943. The 4th would also be the first fighter group to be selected to escort the heavy bombers of the USAAF on their first shuttle run, landing in Russia before returning home.

Not only did they undertake many ‘firsts’, but the 4th FG gained an undeniable reputation, between the 5th March and 24th April 1944 they earned a Distinguished Unit Citation when they shot down 189 enemy aircraft whilst destroying 134 on the ground. You cannot mention the 4th without mentioning the name of Donald M. Blakeslee, credited with 16 kills, he was a brilliant fighter pilot who retired from the USAAF as a Colonel. Blakeslee was considered one of finest combat fighter leaders of the Second World War who shunned publicity even refusing to paint ‘kills’ on his aircraft, and he was known, on several occasions, to give kills to rookie airmen. Blakeslee initially flew in 401 Sqn (RCAF) before transferring to 133 Sqn and then the USAAF when they transferred across. He was a remarkable man, a great leader who was looked up to by all those who flew with him, he sadly died in September 2008 leaving a daughter. All-in-all, the 4th achieved quite a remarkable record considering they were initially volunteers of the American air war in Europe.

The 4th FG would remain at Debden thought the war, leaving it only when the RAF required the return of the airfield in July 1945, at which point the whole group packed up and departed for Steeple Morden in Cambridgeshire.

![Airmen of the 4th Fighter Group ride in the back of a jeep at Debden air base. A P-47 Thunderbolt is in the background of the shot. Passed by the U.S. Army on 2 October 1943, THUNDERBOLT MISSION. Associated Press photo shows:- Pilots at a U.S. Eighth Air Force station in England are taken by truck from the Dispersal room to their waiting P-47's (Thunderbolts) at the start of a sortie over enemy territory. L-R: Lt. Burt Wyman, Englewood, N.J. ; Lt. Leighton Read, Hillsboro, W.V.; F/O Glen Fiedler, Frederickburg, Tex. AKP/LFS 261022 . 41043bi.' [ caption].' Passed for publication ....1943'. [stamp].](https://i0.wp.com/www.americanairmuseum.com/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/freeman/media-377283.jpg)

Taken almost a year to the day the US forces moved in, airmen of the 4th FG are taken ot heir P-47s before departing on a mission over enemy territory. The aircrew are: L-R: Lt. Burt Wyman, Englewood, N.J. ; Lt. Leighton Read, Hillsboro, W.V.; F/O Glen Fiedler, Frederickburg, Texas. (FRE 28 – IWM).

With that 1943 faded into 1944, the jet age was dawning and the end of the war nearing sight. In the July, 616 Squadron appeared with the Meteor, Britain’s first operational Jet aircraft. The squadron detachment stayed here until early 1945 when they moved on to Colerne and eventually the continent.

This move would signify the end of operational flying at Debden. The RAF retained the site reforming the Empire Flying Training School here on 7th March 1946 by merging both 12 and 14 Radio Schools into one. Flying a number of aircraft including Proctors, Tiger Moths, Ansons, Dominie and Lincoln IIs until October 20th 1949 when it was disbanded and Debden became the Royal Air Force Technical College, Signals Division. After a further name change the unit was finally disbanded on April 8th 1960, after it had operated a variety of aircraft including an: Anson, Air Speed Oxford, Spitfire XVI, Lincoln and Varsity.

Between 1963 and October 1973, Vampire F. MK.3 VF301 stood outside Debden’s front gate as guardian, one of several that have been here. It is now sits in the Midland Air Museum at Baginton in the markings of 605 (County of Warwick) Sqn as ‘RAL-G’.

Although remaining open, the airfield was used for a number of public displays and as a race track, including in 1966, the RAF Debden Motor Gala which featured Donald Campbell’s car, Bluebird CN7, in which Campbell set the land speed record in 1964. Parts of the site are still used for racing today by the Borough 19 Motor Club*3

In 1975 the airfield officially closed although 614 Gliding School (later 614 Volunteer Gliding School) remained on site using it for flying, until they too departed moving to Wethersfield in 1982.

The army took over the site when the RAF Departed and they remain there to this day.

Debden, because if its post war usage, is a remarkably unique site, but whilst many of the original buildings remain intact, some even being listed as Grade II buildings*4, access is not permitted to the general public and therefore very little can be seen without prior permission. From public roads, high fences and thick hedges obscure most views although from the south, parts of the runway, and several dispersals can be seen quite easily.

By keeping the gate house to your right and passing along the road east to west, you pass the current accommodation area, Guard House and modern buildings used by the current Army owners. Continuing along this road soon brings you to the memorial. Whilst there is no official parking space here, there is a grass verge opposite the memorial where you can safely park your car off the busy main road. Behind the memorial is the north-south runway, still in full width, in which a small section of it can be seen as it rises and dips over the hill. Returning toward the main entrance brings you to a parking area on your right, where public access is permitted to Rowney Wood. Here there are a small number of original buildings still left along with former roads / and taxi ways. During its US occupation, there were five Blister Hangars located here, today only a couple survive, both in current use by local companies.

Like many former airfields and military sites, Debden has been identified as a possible housing location, with the potential for the construction of 55,000 homes. The announcement to close the barracks was made on November 7th 2016, as part of the ‘Better Defence Estate’ strategy, in which 91 MOD sites across the country will close by 2040. Government figures say that the move will save £140 million by closing these sites which also includes the US base at Mildenhall.*5

Considering the history of RAF Debden and the current status of its buildings, the restrictive nature of the site is also its guardian angel. However, with the axe looming heavily overhead, what will become of this site in the future? Its runways will no doubt be dug up, the older non-classified buildings could be demolished, its pathways and taxiways removed. Debden is in danger of disappearing for good leaving only small traces of this once famous airfield that not only took part in the Battle of Britain, but whose airmen defended London in what was very much our darkest hour.

Sources and further reading.

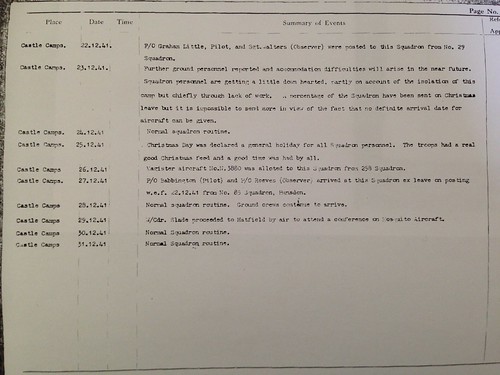

*2 AIR 27/703/17 National Archives

*3 ‘Borough 19 Motor Club’ website has details of their race activities.

*4 One such building is the Sector Operations Block, built in 1938, to the designs of J.H. Binge of the Air Ministry’s Directorate of Works and Buildings (drawing no. 5000/137).

*5 The story was highlighted in the Saffron Walden Reporter website accessed 11th October 2017.

Royal Air Force Police Flights who were at Debden have photos and information on their website.