This airfield forms the second stop on our Essex trail and is an airfield that is probably unique in that it was named after a General. After leaving Matching Green, we travel a short distance away and stop at the former base Andrews Field.

RAF Andrews Field

Andrews Field (officially Great Saling or Station 485) can be found nestled in the Essex countryside, not far from Stansted airport, about 3 miles west of Braintree. It has the unique honour, among many, to have been the first airfield designed and built for the USAAF in England.

Construction began in the summer of 1942 as a bomber station for the then fledging Eighth Air Force. Units from the 96th BG would start to arrive mid 1943 and their first operational duty would come in the middle of that same year. Heavy bombers of the 96th would go on to perform a strategic bombing role for the remainder of the Second World War, although not from Andrews Field.

Great Saling was renamed Andrews Field in honour of Lieut. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, who was killed when his B-24 crash-landed in Iceland on 3rd May 1943. Andrews was the eighth American general to lose his life (or to be reported missing in action) since the war began, and was known as a ‘doer’, once quoted in the New York Times as saying: “I don’t want to be one of those generals who die in bed.”*3

The airfield was built as a Class A airfield, with accommodation situated to the north-eastern side of the airfield. A communal site, two mess sites, six airmen accommodation sites, two WAAF sites, a sick quarters and a sewage works would accommodate upward of 3,000 officers, airmen, WAAFs and ground crews. The airfield, with the pinnacle of the ‘A’ pointing north, had three hard runways, the main (2,000yds) running east-west and two secondary (1,400 yd) running north-west to south-east and north-east to south-west respectively. A perimeter track with 50 hardstands joined the three runways together. Further storage and maintenance ‘sheds’ were provided by two T2 hangars, one to the south and one to the east. A bomb store, for small bombs, incendiaries and fusing, was also to the south next to Boxted Woods. The main administrative area was to the east, where the main entrance led out of the site to the accommodation areas. The technical aspects of Great Saling were widely spread and in comparison to many other airfields of this nature, quite thinly catered for. With the majority of the work being undertaken on this side of the airfield, the western side was left primarily for aircraft dispersal.

B-26 Marauder (s/n 43-34132) “Patricia Ann” of the 450th BS undergoing an engine test at Andrews Field. The aircraft collided with another B-26 (42-96279) over Beauville Airfield, it suffered damage but was able to return*1.

The first but not primary residents, were the heavy B-17s of the 96th BG, 4th BW, Eighth Air Force. Activated in July 1942 at Salt Lake City Utah, they trained on B-17s from the start of their inception. Moving to the United Kingdom in the following May, they would stay at Andrews Field for only one month before moving on to nearby Snetterton Heath on 12th June 1943. The 96th would operate four squadrons (337th, 338th, 339th and 413rd BS), attacking targets such as shipyards, harbours, aircraft factories, and major industrial targets across occupied Europe. Later in the war, they would receive a Distinguished Unit Citation before their return to the United States post war.

With their departure, Andrews Field would be passed over to a new unit, the 332nd BG, who were to be the largest and most major operational unit to serve at Andrews Field for the duration of the hostilities.

The USAAF was not generally associated with medium bombers, and the introduction of the Martin B-26 Marauder, would bring a whole host of issues. Rushed into service, it was to gain notoriety for poor handling, regular engine failures, weak undercarriage and high stall speeds that led to a string of accidents and crew deaths. The aircraft soon gained a collection of unsavoury names; ‘Widow Maker‘, ‘Baltimore Whore‘ and ‘Flying Prostitute‘, reasons for which were born out in its early days of flying.

B-26 Marauder (s/n 41-18276) “Pickled Dilly” of the 322nd BG. Later shot down 13km south of Abbeville, by Bf-109G-6 (JG301/1), July 8, 1944. 3 KIA 4 POW*2

The 322nd BG, activated at MacDill, Florida, trained with this particular aircraft and Marauder Squadrons soon found themselves transferring across the Atlantic to bases in both Suffolk and Norfolk as part of Eaker’s Eighth Air Force.

General Eaker however, soon decided that the low flying, medium bombers were adding little to his strategic bombing campaign, and so placed all the Marauder units under the control of the VIII Air Support Command, very much a back seat of the mighty Eighth’s activities. Coinciding with this move, was the decision to move all Marauder units of the 3rd Wing south so as to be within easy reach of the continent and more able to support the impending invasion. The first units to be affected were the 386th (to Boxted), the 322nd (from Rougham to Andrews Field) and the 323rd (to Earls Colne). The headquarters for these also moved south, taking up new residency at the less luxurious Marks Hall, an Elizabethan mansion!

After a series of disasters at Rougham, the 322nd, arrived at Andrews Field on June 12th 1943. The four squadrons (449th, 450th, 451st and 452nd BS) all returned to action in the July, following a series of intense low-level training duties. Better successes followed, and this led to a growing belief in the Marauder’s capability in proven hands; the future began to look brighter for the aircraft. The 322nd went on to use their new skills, attacking targets that included airfields across the lowlands, power stations, shipyards and the rail networks. Success flourished and the 322nd would eventually earn themselves both notoriety and a DUC for their high performance; if nothing else it was a reputation that stopped the Marauder crews being on the wrong end of B-17 crew jokes.

The 80,000 gl Braithwaite Water Tower at Andrews Field

On October 6th, 1943, the four units of the VIII Air Support Command flew their last mission as part of the Eighth. Now there was a new control, the Ninth Air Force had moved to England. A new focus and more low-level strikes against the enemy led the preparation for the invasion. Coastal defences were hit and airfields in the northern area of France were targeted as part of operation STARKEY, the allied plan to fool the Germans into thinking a full-scale attack would take place around the channel ports.

Following the June invasion, for which the 322nd played a major part, they went on to continue supporting Allied ground movements. Battles at Caen and St. Lo helped the Allied forces advance through France: bridges, railway junctions, defensive positions and ordnance depots all came under the focus of the 322nd.

As the Allies moved further in land toward Germany, so too did the Marauders. In September 1944, the 322nd left Andrews Field and moved to Beauvais in France. They continued to support the Allies into the German Heartland performing their last mission on April 24th 1945, before commencing inventory duties in Germany and then returning to the US for disbandment on 15th December 1945.

By the end of their tour, the 322nd had performed remarkably. The Marauder had gone from one of the most despised aircraft to the perhaps one of the most respected. Its ability to perform in good hands, and its sturdy airframe, reflected its remarkably low loss rate, 0.3 %, 13 losses in only 4000 sorties.

After their departure, Andrews Field was passed to RAF control and a considerable number of fighter units would pass through here. First came the Mustang IIIs of 316 Sqn, who arrived in August 1944, staying until September 1945. The October of 1944, saw yet more Mustangs arrive, with 19, 122, 129, 315 and 316 sqns again all with the Mark IIIs. By now Andrews Field was a very busy base, and even more units were to pass through. In December, 309 Sqn arrived staying until August 1945, and it was during this year (1945) that 65 Sqn brought the updated Mustang IV as did 303 Sqn later in the August. A monopoly of American hardware was only broken for two months (June to August 1945) by the Spitfires of 276 Sqn.

Then as the jet age dawned and Meteors began to arrive, two squadrons would operate the aircraft from Andrews Field; both 616 Sqn and 504 Sqn (albeit for a short period only) would fly the MK.III, transforming the sound from piston engines to jet engines. As December 1945 came so did the departure of the 303 Sqn and the last remaining Mustangs, a move that signalled the end of military action at Andrews Field. Following this, the airfield was mothballed and finally put into care and maintenance.

Andrews Field was to produce some remarkable records during its operational time. The first by B-26 ‘Mild and Bitter‘ s/n 41-31819, of the 450th BS, was the first Allied bomber to pass 100 operational missions (in Europe). A second, ‘Flak Bait‘, s/n 41-31773, became the first to surpass 200 missions – both remarkable feats when at that time few pilots relished the thought of flying just one mission let alone two hundred.

Post war, the airfield was used for a multitude of roles, eventually having much of its infrastructure removed and returning to a primarily agricultural role. However, aviation grew from the ashes and flying thrives once again through light aviation as Andrews Field Aviation. Offering a range of flying lessons, they keep the spirit of Andrews Field alive long after the last military aircraft departed on its final journey. Using a grass runway that follows the line of the original, it is one of the few reminders that an airfield existed here many years ago.

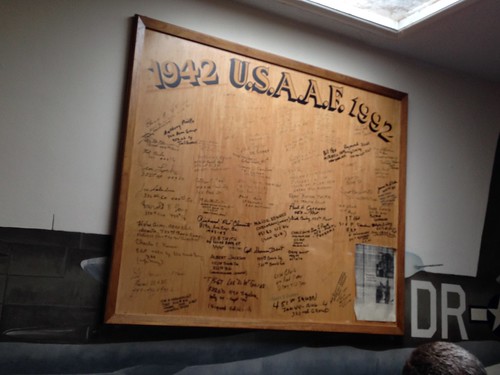

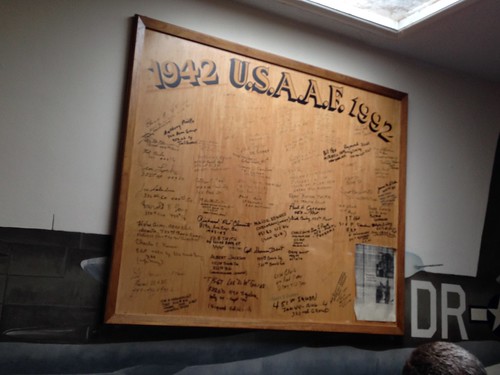

A memorial board in the airfield clubhouse

Visiting Andrews Field today, there is little of its former life left. The runways, buildings and perimeter tracks have all but been removed. Much of the evidence of its existence lies in the nearby village of Great Saling. The 80,000 gl high level water tower (Braithwaite built to design 16305/41) stands on the former Site 3, now a playing field, and a defensive pill-box hints at the area’s historical use. The main accommodation areas are now either all built upon with small housing estates or ploughed up for agricultural purposes. The original entrance from the main road is today the entrance to a small quarry.

Driving away from the village to the rear of the airfield takes you along the former north-western perimeter track. Down here almost buried under the hedgerow are the steep banks of the firing butt. The road continues round to the southern side of the site, again utilising part of the original perimeter track. Entering the site, takes you alongside the runway to the clubhouse and parking areas. From here one of the remaining two T2s can still be seen, lurking in amongst the tress, as if defiant to development.

A rather unusual addition to the site is a somewhat forlorn Dassault Mystere IVA jet, gradually decaying in the British weather. It certainly has seen better days, and maybe one day it too will rise from the ashes and become a thing of aviation beauty once more.

A memorial to those who built the airfield can be found where the entrance to the sick quarters were, and a further memorial can be seen along the road linking Great Saling and the A120 in memory of the crews of the 322nd BG. Inside the clubhouse is a mural and photos of the airfield whilst under construction.

The mural painted to commemorate the crews of the 322nd.

Andrews Field is an airfield that has clung onto its heritage, but whilst much of its former life has gone, the sound of small piston engined aircraft provides something of a reminder of the mighty engines that once relentlessly throbbed on this amazingly historical site.

After leaving Andrews Field, we travel a few miles west back again toward Stansted Airport. We stop at Great Dunmow and the neighbouring church at Little Easton.

Sources and further reading

1 Photo Roger Freeman Collection, IWM, FRE4482

*2 Photo Roger Freeman Collection, IWM, FRE1187

*3 New York Times published May 5th 1943 (accessed May 26th 2018)

“The Mighty Eighth“, (1970), Roger Freeman, Arms and Armour,

“RAF Squadrons“, (1998) CG Jefford, Airlife

A number of detailed and remarkable websites exist around the B-26, each is worthy of a visit.

http://www.billsb-26marauder.org/

http://www.markstyling.com/b26s.01.htm (art work)