There are few Bomb Groups who got through the war unscathed. Some earned notable awards, many earned notable nicknames. There are none more though than that of the 100th Bomb Group of the United States Air Force, a groups of men who fought in many of Europe’s most fearsome air battles, suffering many great loses but also achieving great successes.

In this review of Trail 12 we look again at the airfield at Thorpe Abbots, and the history behind the derelict buildings and the concrete remains, we see how the 100th BG earned themselves that most unsavoury name ‘The Bloody 100th‘.

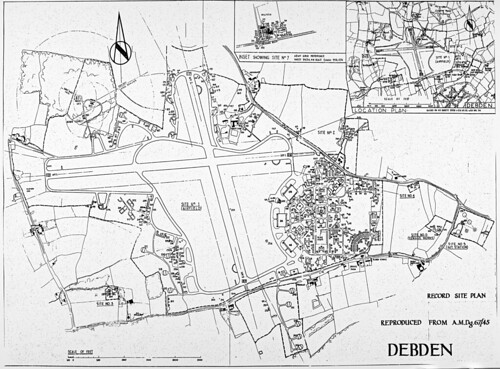

Thorpe Abbotts (Station 139).

Opened quite late in the war, (April 1943), Thorpe Abbots would only be active for a short period of time. But during these months, it would be home to one major air group, the 100th BG of the US Eighth Air Force, who would gain the unsavoury name ‘The Bloody 100th’. Their legacy would become well-known, it would be a legacy connected with death and destruction, and would be one that would live on for many years, even after the cessation of conflict in Europe.

The first units of the 100th BG would arrive in June 1943, and would operate continuously here until the cessation of conflict in 1945. The site would never see any further action after this, being returned to the RAF who retained ownership until its final closure in 1956. Now totally agricultural, it boasts a superb museum as a memorial to those who gave so tragically flying with ‘The Bloody 100th’.

The 100th’s name developed as a result of losses sustained by the group, which in actual fact were not significantly worse than any other Bomb Group of the US Air Force at that time. However, throughout their 306 operational missions over occupied Europe, 177 aircraft along with 700 lives were sadly lost in what were some of the most difficult and terrifying air battles of the Second World War.

Designated Station 139, Thorpe Abbots was built to Class A specification, with three concrete and woodchip runways in the form of an inverted ‘A’, with the cross of the A being the main runway running east to west. Being a bomber base it had 36 pan style hardstands and 16 spectacle hardstands around the perimeter. Maintenance was carried out in two T2 hangars (a type A to drawing 8254/40, and a standard T2). The technical area, accommodation areas and even the bomb store were very unusually all nestled close together in the south-western corner of the site, giving the whole airfield a compact feel.

With two communal sites, six airmen sites, two WAAF sites, a sick quarters and sewage works, it was a large accommodation area capable of holding 3,000 men and women of mixed ranks. All the accommodation areas used a range of standard huts, Nissen, Romney, Seco, Thorn and Orlit, all of which appeared on site.

Being a large base, it was, like many of its counterparts, a little town in its own right, with a barber’s shop, a cobblers, grocery store, a gymnasium and squash courts. It also had an on site plumbers, a cement store and a carpenter’s shop.

Although the journey of the 100th started with the activation on June 1st 1942, little occurred until later that year, when the collection of 230 enlisted men and 26 Officers arrived at Walla Walla, Washington, under the guidance of the Group Adjutant Cpt. Karl Standish. He began to organise the cadre into something worthwhile, and as more men arrived the ranks began to swell and the 100th began to take shape. The four squadrons: 349th (led by Cpt. William Veal), 350th (Cpt. Gale Clevan), 351st (Cpt. John Kidd) and 418th (Cpt. Robert Flesher), formed bonds and very quickly, and very soon after, the air echelons would begin to arrive, bringing with them brand new ‘straight out of the factory’ B-17Fs.

Their next move came at the end of November with a move that took them to Wendover Field, Utah, followed by, Sioux City and then Kearney Air Base in Nebraska, their final major US base before leaving for the UK in May 1943.

After the ground and air echelons split for their transition, the air echelons flew to bases in Newfoundland, where they departed across the northern route to Prestwick at the end of May. The ground echelons then carried out ground training before departing on the “Queen Elizabeth” on the 27th May, many men being confined below decks because of the overcrowding on the upper decks.

The Queen Elizabeth finally made Greenock, and the men began unloading, the transition from the US to the UK being a shock to many as they clambered aboard the small ‘box cars’ size trains. That night they arrived at Poddington, their first base, and following a poor night’s sleep they received their initial introduction into the British way of life.

The 100th’s arrival at Thorpe Abbotts was not a pleasant one, the base was unfinished, accommodation was lacking and overcrowded, and food supplies were poor to say the least; this was not going to be an easy ride by any means.

Finally, in June, the air echelons began to arrive, the ground and air crews began to work on their machines, rehearsing, tweaking instruments and flying around the local area, until just after midnight on June 25th 1943, the order came through; they were to fly their first mission early that next morning.

The 100th were the third B-17 group to join the Mighty Eighth, as part of the new and reorganised 4th Bombardment Wing, they would join with the 379th BG (Kimbolton) and the 384th BG (Grafton Underwood), both also B-17 groups.

On that morning the aircraft would depart Thorpe Abbotts at 06:00 hrs, and whilst flying out over the North Sea, the formation would be joined by another B-17, with no top turret and the letters ‘VGY’ painted on it. No-one knew what it was, or where it had come from, and suspicions quickly arose about its authenticity. The ‘alien’ ship remained with the formation up until the target at which point it departed and “all hell broke loose”. The formation consisting of these new recruits was ragged and the experienced Luftwaffe pilots took full advantage of this. Focusing on the low squadron first, they fired a barrage of explosive shells into the fuselage’s of the B-17s. That afternoon three aircraft and thirty airmen failed to return home to Thorpe Abbotts, the war had hit home, and hit home hard.

Robert H. Wolff’s crew. L to R Back Row: Ira Bardman, Alfred Clark, William ‘Casey’ Casebolt, James Brady, Arthur ‘Eagle’ Eggleston, Willis ‘Browny’ Brown . Front Row: Charles ‘Stu’ Stuart, Fredric ‘Buzz’ White, (aiming at the enemy) Bob Wolff, Lawrence ‘Mac’ McDonell. The photo was taken after Regensburg for publicity purposes. (@IWM FRE 905)

Over the next month, there were many aborted and scrubbed missions, this continued raising and dashing of hopes set the men on edge but what few missions they did fly, they manged to get through relatively unscathed.

The end of July 1943 saw the official hand over of Thorpe Abbotts from the RAF to the USAAF, with Sqn. Ldrs. Lawson and Bloomfield representing the RAF and Col. Harding the USAAF.

On August 17th 1943, on the anniversary of the Eighth’s operations from England, the men of the 100th sat in the briefing room awaiting the revealing of the target for the day. The anticipation however, was soon replaced with trepidation as the route map revealed a line that would take them deep into the heart of southern Germany, to the Messerschmitt plant at Regensburg. This would be no ordinary mission though, they were to not return to Thorpe Abbotts that day, but instead, they were to complete the first shuttle mission by the Eighth Air Force of the war, flying on to land in North Africa.

After an initial postponement because of mist, the green light was finally given and the aircrews started their engines. One by one they departed Thorpe Abbots toward the skies above Germany. The 100th were in the unenviable position of ‘tail end Charlie’ being the low squadron at the rear of the formation. Added to this the 100th BG found themselves unprotected due to miscalculations in timing, and as unprotected ‘tail-end Charlies’, they were easy prey for the fearsome and hunting Luftwaffe. For two whole hours the defenders attacked from every possible angle, venting their determination on the lowly B-17s. The sky was littered with downed aircraft and falling wreckage. The B-17s were subjected to harrowing attempts to bring them down, air-to-air bombing from Ju-88s, and rockets fired from BF-109s just added to the mayhem of exploding cannon shells and bullets.

During this engagement B-17 #42-30311, piloted by Lt. Tom Hummel was attacked by Rudolf Germeroth in Bf 109G-6 of J 3/1. The aircraft was seen to explode and fall from the sky. The two waist gunners Ken O’Connor and Dick Bowler were killed whilst the remainder of the crew escaped the wreck and were taken prisoner.

Bombing over the target was accurate and reports sent back to England hailed the mission as a total success, The Messerschmitt factory being totally destroyed, and along with it unbeknown to intelligence, secret jigs for the manufacture of Me 262 jets. But the price had been high, of the twenty-one aircraft sent from the Thorpe Abbotts group, nine had been lost and ninety men were either dead, captured or missing. Of all the groups who had taken part, the 100th had suffered the most, the lead group protected by P-47s coming off much more lightly.

The Regensburg mission would be a turning point for the 100th, their luck would run out and very soon they would earn themselves the unsavoury nickname ‘The Bloody 100th‘, a name that would stick with them for the duration of the war and beyond.

For their action in this mission, the 100th (and the entire division) would earn themselves a Distinguished Unit Citation (D.U.C.) an award now becoming a regular feature amongst the brave crews of the Eighth Air Force.

In the Citation, the Secretary of War, G.C. Marshall said:

“The 3d Bombardment Division (H) is cited for outstanding performance of duty on action against the enemy on 17th August 1943. This unprecedented attack against one of Germany’s most important aircraft factories was the first shuttle mission performed in the theatre of operations and entailed the longest flight over strongly defended enemy territory yet accomplished to this date. For 4.5 hours the formation was subjected to persistent, savage assaults by large forces of enemy fighters…

…The high degree of success achieved is directly attributable to the extraordinary heroism, skill and devotion to duty displayed by the members of this unit.”

During the September, the USAAF was reorganised again, the 4th Bombardment Wing now becoming the 3rd Bomb Division, 13th Combat Wing, a move that heralded little more than a change in aircraft markings. September would also be a notable month for other reasons. The mission on the 6th to Stuttgart would be a disaster for the USAAF, a deep penetration mission that saw over 400 aircraft combine in the skies over Germany. It was during this mission that B-17 #42-30088 ‘Squawkin’ Hawk II‘ would suffer from head on attacks by Luftwaffe aircraft who pounded the B-17 with 20 mm cannon shells. In the attacks the co-pilot (F/O. Harry Edeburn) was fatally wounded, the bombardier and navigator Lt. Peter Delso and Lt. Russ Engel were both severely wounded and the pilot, Lt. Summer Reeder was sprayed with metal as the nose of the B-17 shattered. With poor control and no oxygen, Reeder dropped the aircraft some 14,000 ft at an unbelievable rate of around 300 mph, before playing cat and mouse with the Luftwaffe fighters who were determined to finish off the damaged aircraft. By singing and telling jokes, the severely injured Reeder assisted by the badly wounded navigator, manged to reach England and without brakes or hydraulics, managed to put the aircraft down on a fighter airfield in England.

‘Squawkin Hawk II‘ would go on to become the first 100th BG aircraft to complete 50 missions covering a staggering 47,720 combat miles. She returned to the US in May 1944 where she was eventually sold for scrap.

After completing 50 missions, “Squawkin’ Hawk II” was covered with autographs before being sent back to the US for retirement and eventual scrapping.(@IWM FRE 4124)

During this disastrous mission many aircraft would run out of fuel, five made for Switzerland including ‘Raunchy‘ from the 100th BG in which Joe Moloney, the ball turret gunner, would be killed whilst trying to ditch. He would take the dubious honour of being the first US airman killed in neutral Switzerland.

It was also at this month, that the 100th would suffer another major blow and to rub salt into the wounds, they would not even get credit for it.

After a cancelled mission on September 24th 1943, the men of the 100th were raised from their beds for a practice mission over the North Sea, a ‘mission’ that would test their ability as Pathfinders. With bombs still in the aircraft from the morning’s preparations, skeleton crews and semi prepared aircraft took off from several bases across East Anglia.

They were to form up with P-47s over the Wash and then fly out over the sea and practice bombing. When a collection of aircraft appeared on the horizon it was assumed by the bomber crews that it was the friendlies arriving at last. The reality of it was sickening. Diving out of the sun Luftwaffe fighters from JG 3/II attacked the formation, rallying 20mm cannon shells in to the B-17’s wings and bodies. One aircraft, #42-30259 “Damifino II” piloted by Lt. J. Gossage crashed into the sea. Five crewmen were plucked from the water by Motor Torpedo Boats (MTB) hunting German ‘E’ boats, five men remained missing presumed dead.

Yet more difficult times lay ahead. The October raid to Munster saw only one of fourteen aircraft return home – 120 crewmen were missing in action that day. As aircraft were hit from head on, the formation split. Aircraft dodged falling debris and exploding B-17s as rockets were launched at near point-blank range in a forty-five minute frenzy of slaughter.

This disastrous mission would see the tally of lost airmen rise to 200 in just one week, the loss could not be hidden and Munster would simply add another black chapter to the already darkening book of the 100th’s war. Even the one year celebrations at the end of October failed to cover the feeling of loss shrouding the base, a feeling as thick as the autumn fogs preventing flying from taking place.

The cold winter of 1943/44 saw more fog, rain and cold, the dismal weather allowing only a few missions to go ahead. But as spring warmed the ground, the softening of the German defences in preparation for Operation “Overlord” could begin. ‘Big Week’ of February 20th – 25th, saw the 100th in action again – Brunswick on the 21st. March saw another milestone etched in the annuals of history as the 100th took the war directly to the heart of Germany and Berlin. Over three days the 100th would target the German capital, the first on the 4th, followed by the 6th and then the 8th. The 4th would see the 100th achieve the first blood, shooting down their first German aircraft over Berlin.

Each attack brought new challenges. In the first mission the weather forced many aircraft to abandon the flight and return home, the 100th, persevering lost one aircraft that day. On the 6th, the loss was much higher, fifteen aircraft went down and then another single aircraft on the 8th; 170 men were missing from those missions.

For their action, the 100th would receive their second DUC, albeit a year later. In the General orders 3rd March 1945, No.14 it said:

“The 100th Bombardment Group (H) is cited for outstanding performance of duty in action against the enemy in connection with the initial series of successful attacks against Berlin, Germany, 4, 6, and 8 March 1944…”

For the remainder of the summer the 100th would attack oil fields. bridges, and gun positions. They would provide support at St. Lo and Brest in August. Marshalling yards would also come under the focus of the 100th, the Ardennes and the assault across the Rhine.

On 16th September 1944, a letter was sent by Major General Earl Partridge (U.S. Army) to the Commanding Officer of the 100thBG extending his gratitude to all the personnel at the station on their 200th mission. He concluded:

“Please extend to all Officers and Men on your station my appreciation for the outstanding work which they have done. Their achievements reflect the highest credit upon themselves and the Army Air Forces as a whole.”*1

As part of the celebrations a B-17 was sent to London to collect a “huge supply of Whisky and Vodka”, no doubt a considerable amount was consumed that night.

Eventually the war would come to a close and the 100th perform their last mission on April 20th 1945. They would lick their wounds and prepare for a well-earned return to the US.

By the end of its war-time operations the 100th BG had flown nearly 9,000 sorties, in over 300 missions, dropping over 19,000 tons of bombs. They would be credited with the destruction of 261 enemy aircraft, with another 240 damaged or probable. They earned two DUCs and the French Croix de Guerre with palm. Far from being the worst in the 8th Air Force, the 100th’s reputation for accuracy, and overall low operational loses made it one of the most outstanding Bomb Groups of the Air Force.

Finally leaving in December 1945, the 100th would eventually return to serve over the skies of the UK once more as the 100th Refuelling Wing based at nearby RAF Mildenhall.

After the 100th departed, Thorpe Abbots was returned to RAF ownership, no further military flying took place and the site remained inactive. Eventually in 1956 the airfield was closed and the site then sold off to private ownership. Many of the runways and perimeter tracks were removed for hardcore, and the buildings fell into disrepair.

Today, the site houses a museum utilising the old original control tower and a small number of other buildings. Tucked neatly away amongst the beautiful countryside of Norfolk, this museum is more than worthy of a visit.

Visible remains of the airfield are restricted to mainly perimeter track, but remnants can be found with a little effort. In the woods to the east of the tower, buried in amongst the undergrowth, are the remains of buildings including the Battle Headquarters which would have commanded excellent views across the field in the case of attack.

The perimeter track has been partially utilised and turned into road, from which larger sections can be seen. A number of admin blocks, stores and a range of accommodation buildings are now engulfed by trees and vegetation but still survive and are all very much on private land.

Whilst many buildings remain hidden away, the dedication of a few volunteers keep the memories and lives of those who gave so much alive, and enable the history of Thorpe Abbots airfield to continue on for future generations.

Sources and further reading.

*1 100th BG Quartermaster Log via their website August 2019.

Freeman, Roger A. “The Mighty Eighth” (1986) Arms and Armour

Arnold, Henry. H., “Contrails, My War Record: A history of World War Two as recorded at U.S. Army Air Force Station #139, Thorpe Abbots, near Diss, county of Norfolk, England” (1947) World War Regimental Histories Book 194.

Further details of the 100th BG and information about the museum can be found on the museum website.