The influences of both the American forces and RAF Bomber Command extend far beyond the boundaries of the Midlands region visited previously in Trail 6. East Anglia saw by far, the largest influx of both air and ground crews and their associated hardware of the entire war, and although the airfields built at this time were designed to last only a few years – basically as long as the war would last – many continued on beyond the1940s. However, and like their Midland counterparts, many would have a lasting effect on both the locals and the landscape of their respective regions.

In Trail 7, we visit the northern part of Norfolk, not far from the coast where it borders Cambridgeshire to the west and the North Sea to the north and east. At the first stop on this trail we visit a site that was once one of Norfolk’s most prestigious airfields, where not one, but two VCs were awarded to airmen of the RAF.

Not far from the county border with Cambridgeshire, we look at this once busy airfield to see what is left and take a look at the incredible history that was RAF Downham Market.

RAF Downham Market (Bexwell)

Early Aviation Links

Located in the corner of the A10 and A1122, 10 miles south of Kings Lynn and 15 miles north-east of Ely, RAF Downham Market (known also as Bexwell) was only open for four years. Yet considering its relatively short life, it created for itself a unique history that was, and remains, almost unprecedented in aviation history.

But, before Downham Market even had an airfield, the town would gain its own aviation claim to fame, and one that goes back as far as the First World War.

Throughout World War I, Baron von Richthofen was a major thorn in the side of allied pilots, and it would be a Downham pilot that would become one of the few to not only survive an aerial encounter with the prestigious pilot, but also meet him in person after he had shot him down.

Algy Bird – a mere novice at the time, and one who, according to Richthofen, flew like a “very skilful pilot, who even at a height of 50 metres did not give up” – would fall to The Red Baron’s guns.

During the aerial skirmish between the hunter and the hunted, Bird was injured in the shoulder, forcing him to land behind enemy lines where upon he was captured and held as a prisoner of war. Before his incarceration however, he would meet his adversary, von Richthofen, where they would talk about their exploits. A relatively brief encounter, Bird was soon moved on, remaining a prisoner until the war’s end. Once peace was declared, Bird was repatriated returning to his home in Downham Market where he continued to work in his family’s flour mill.

However, this was not the only connection between Downham Market and aviation at that time. In addition to this remarkable story, land at Bexwell, near Stonehills Farm, had been earmarked as an emergency landing ground during the war. Situated about half a mile south of the site later chosen for the Second World War airfield, it appears to have been used only occasionally. Nevertheless, it was marked with a large white cross to make its presence visible to pilots flying overhead.

Neither of these events though, influenced directly, the decision that would occur in the late 1930s and early 40s, putting Downham Market clearly on the aviation map.

As the threat of war grew again, land on the outskirts of the town was quickly identified as a suitable site for a full-scale military airfield. The news was not initially welcomed by the local population though: the increased traffic, aircraft noise, disturbance to their way of life and even the possibility of raids, put a barrier up between those making the decisions and those living peacefully in the area.

The site that would become Bexwell aerodrome, as it was known locally, lay on land, 117 feet above sea level, partly owned by R. Cox Farms and partly on land owned by the Pratt family of nearby Ryston Hall. This meant that compulsory purchase orders were given to both parties to secure the site after which a minor road was closed (reinstated post war) and numerous hedges were pulled up to allow the construction work to begin.

Construction of RAF Downham Market

Built under the direction of the Air Ministry Works Directorate, and constructed mainly by W. & C. French Ltd. of Buckhurst Hill, Essex, Downham Market was originally established as a satellite airfield for nearby RAF Marham. It later developed into, and was officially recognised as, a bomber station in its own right.

Operating under 2 Group before transferring to 3 Group and then eventually to 8 PFF (Pathfinder) Group Bomber Command, it achieved operational status not long after opening, prior to gaining its own parent status on 3rd March, 1944.

By opening up a gravel pit at the nearby village of Crimplesham, the constructors were able to ferry large quantities of gravel and sand a very short distance to the site at Bexwell, and so the rate at which the airfield was built was very rapid indeed. The biggest issue for locals however, was that not being a tarmacked road, it quickly became a mire of mud and water.

Construction of the airfield was a monumental task, carried out by squads of Irish navvies who worked tirelessly to transform open land into a fully operational military station. They laid miles of electrical wiring, poured thousands of tons of concrete (enough for a ten-mile long motorway) and erected numerous steel-framed huts that would house personnel and equipment.

Following the standard design of a Class ‘A’ airfield, the station was carefully planned with a clear separation between the operational and living areas. The technical site and runways lay to the north of the main Downham Market to Swaffham Road, while the accommodation for officers and airmen was positioned to the south. This layout reflected both practical needs and the disciplined, orderly approach typical of dispersed wartime airfield construction.

Designed as a bomber station – a role it maintained throughout the Second World War – the airfield required substantial runways and a wide network of dispersed accommodation sites. At its peak, it housed 1,719 male and 326 female personnel, the total population amounting to nearly two-thirds that of Downham Market itself.

The accommodation complex comprised an Officers’ site, WAAF Officers’ site, WAAF site, Sick Quarters, two Communal and five dormitory sites. Most buildings were of temporary construction, employing Nissen, Laing, and Orlit designs, all connected by a network of concrete roads and footpaths.

Within these different sites a small town would emerge: a post office, a local produce store, a barbers, tailors and a shoemaker; a gymnasium, education block and eventually a picture house, often utilising the gymnasium as a makeshift cinema.

On the main airfield site itself there would be three concrete runways (approximately 600 to each other) the main being 2,000 yards long running east-west, whilst the second and third ran north-west to south-east and north-east to south-west, each 1,400 yds long and all 50 yards wide. To speed up construction, these runways were built using minimal excavation and were made of 6 inches of un-reinforced concrete, with a later addition of asphalt. It was expected that parts of this would indeed ‘crack’ and ‘break up’, but repairs could, and were, completed in half a day using a soft material underlay with added railway sleepers for strength. On top of these, a quick setting “Cement Fondu” was added instead of Portland Cement the normal material used. *10

The classic ‘A’ formed by these runways, was linked by a three-mile concrete perimeter track with thirty-six original pan style hardstands. At its peak, Downham boasted seven hangers, six ‘T2’ and one ‘B1’ which replaced two of the hardstands thus reducing the number to thirty-four. Only one of these hangars survive here today – the rest being removed post war. Like all bomber stations it had the usual bomb store (to the north-east), a vast technical area on the south side and later a FIDO oil store to the south-east.

The main entrance was opposite Bexwell church, a place frequented by many crews either before or after operations, and where a memorial is located today. The guard room remains at the entrance as are the station headquarters, the crew rooms. and a number of other technical buildings. Located not far from here was the Watch office, complete with briefing room (designed to drawing number 7345/41 adapted by drawing 13079/41), meteorological block and crew interrogation room.

The technical area, consisted of a range of buildings that were standard features on bomber airfields and included designs from the common producers Seco, Laing, Nissen and even Marston. Some local designs were also employed using local construction companies to build them. Most of the buildings, including those on the accommodation site, followed standard Air Ministry designs with spans of 16, 24, or 30 feet. A smaller number were constructed from single-brick walls, 4.5 inches thick.

Although construction progressed at a remarkable pace, when the airfield was officially handed over to the RAF on April 1st, 1942, much of the site was still incomplete. Several huts were yet to be erected, and essential facilities remained unfinished. This rather inconvenient situation proved somewhat fortunate for many of the first arrivals, who, finding no available accommodation on site, were temporarily billeted at the local Temperance Hotel until proper quarters could be provided. To hasten its completion, additional manpower was urgently called upon, and teams were brought in to support the civilian navvies – including personnel from No. 962 Balloon Squadron, who were temporarily redeployed from their base at Pembroke.

Life on the Base

Once open, it was quickly noted by those barracked on the accommodation sites that the local tracks would lead them directly to the town, thus by-passing the main guardroom, a useful bit of knowledge that allowed frequent visits to the local inns and cafes a mere 20 minutes or so walk away.

In time, the people of Downham Market grew fond of the RAF personnel and welcomed them into the heart of their community. The local café, ‘Sly’s’, became popular with airmen much to the joy of local schoolgirls, and ‘Stannard’s Bakery’ offered a regular supply of Woodbines and St. Brunos Flake tobacco. *14

Dances became a regular feature at the Town Hall, while local pubs such as “The Crown” and the riverside “Jenyns Arms” provided popular venues for relaxation and camaraderie. The town’s cinema, “The Regent”, offered daily shows, ensuring that entertainment was never in short supply, and those stationed at the airfield made full use of what the town had to offer.

As in many service towns however, the combination of youthful energy and wartime strain sometimes spilled over into rowdy behaviour. A few incidents of drunkenness led some residents to lodge complaints with the station commander. Yet others were quick to defend the airmen, pointing out that these were young men living under constant pressure and risking their lives nightly. Their sympathy and admiration ultimately outweighed the criticism, reflecting a community that, for all its occasional frustrations, stood firmly behind its ‘brave boys’.

Being the largest town in the area, Downham Market would attract the interests of many other forces personnel too. Marham airmen would often work their way over by whatever means possible, and in one instance, a bike was stolen*14 only to be found later in a ditch – the vague attempt by a Marham airman to get back to base after a night out in the town.

After the Americans joined the war, they too managed to find their way to Downham Market, an added interest to those living in the area.

However, it would take some time for the new station to be ready but that didn’t prevent the airfield from seeing action. When Arthur Harris, called for a ‘maximum effort’ operation on the night of May 30th-31st, 1942, to Cologne, Downham Market would be called into operation fulfilling its role as a satellite for Marham, ready to receive landing aircraft that may be damaged or running out of fuel.

Whilst every effort was made to receive as many aircraft at Marham as possible, three were unable to make it in – two were diverted to Downham Market whilst a third landed at Bodney. The first down, Wellington MK.III. ‘H’ – Harry (BJ796) of 115 Squadron piloted by Pilot Officer Stanford, marking the first use of RAF Downham Market when he touched down at 04:41 hrs. The second aircraft, Wellington MK.III ‘L’ (X3412) flown by Pilot Officer Felt, followed some forty minutes later at 05:02 hrs*12 Both these aircraft were returned to Marham just after 05:50 hrs.

A similar occurrence two nights later saw the second of Harris’s thousand-bomber raids, and with damaged aircraft clogging up Marham, Downham Market was again brought into action to help receive any aircraft they could. A combination of skill and good judgement brought several Wellingtons from 115 Squadron down at the airfield, ensuring the safe landing of all on board.

The start of any large-scale construction project was quick to draw the attention of the enemy, and Downham Market was no exception. An early strafing attack which was described by locals like a “firework display” *14 was followed, in June that year, by a more ‘intense’ attack when the airfield found itself the target of Luftwaffe bombers. The bright flarepath lights, being checked at the time by Squadron Leader Laurence Skan, the Flight Controller, likely caught the eye of an enemy pilot who homed in and began to prepare his attack.

Recognising the approaching engines as not British, Skan immediately rushed back to the watch office and extinguished the lights, plunging the airfield into darkness. His swift action proved vital – the bombs fell harmlessly short, landing around the nearby village of Crimplesham and leaving behind a few new ponds for the locals to discover. Apart from a few broken windows, damaged fences and a closed road for an unexploded bomb, little harm was done – a narrow escape later noted with gratitude by Rev. Reed in his Sunday sermon at the village church*13.

When the airfield at Downham Market was officially opened, it was still in use as a satellite station for RAF Marham, who Between May 1941 and September 1942, used it primarily for 1655 Conversion Unit who were then based at the airfield.

Downham’s first own operational residents, the Stirling MK.Is of 218 (Gold Coast) Squadron, would arrive here on July 8th 1942, transferring in directly from Marham. 218 Sqn would retain this version of the Stirling until February 1943, when the new updated MK.III was brought into squadron service.

Operations and Squadrons

218 Sqn were a long-standing unit, with a history that went back to the First World War. Disbanded in 1919 they had been reborn in 1936 and were posted to France where their Fairey Battles were decimated by the superior fighters of the Luftwaffe. In November 1940, prior to arriving here at Downham Market, the squadron joined 3 Group, with whom they remained operational for the remainder of the war.

On July 6th, 1942, 218 Sqn began preparing for their move to Downham Market, aircraft were stood down, and no operational flying would take place. On the morning of the 7th, thirteen Stirlings departed the parent airfield RAF Marham, and after completing the 10-mile, straight line flight, they arrived at Downham Market just fifteen minutes later. The ground staff all transferred by road, and by midnight, the entire squadron had moved over, and personnel were settling into their new quarters. Over the next few days, air tests, fighter affiliations and cross-country flying were the order of the day, the first operational flight not taking place until a week later on July 12th.

That day, Stirling ‘HA-M’ (BF309) piloted by P.O. Farquharson and ‘HA-R’ (W7562) piloted by Sgt. Hartley, carried out a ‘gardening’ mission, the only two crews assigned and briefed. Records show that “The vegetables were planted in the allotted positions. 18,000lb of seed were planted during this effort“*1. But with that rather insignificant and uneventful flight, Downham Market had now officially entered into the war.

Over the next few weeks operations began to build, and targets moved into Germany itself. Lubeck, Vegesack, Duisberg, Hamburg and Saarbrucken were all on the initial list of operations. Apart from early returners due to ice or poor weather, all operations were considered successful, and bombing was ‘accurate’.

On 29th July, a royal party visited RAF Downham Market to see how the crews were settling in at the new station. Led by Air Vice Marshall HRH The Duke of Kent, and accompanied by Sir Louis Grieg KBE CBO (ret.), the party were given an official tour of the airfield by Wing Commander P. D. Holder DFC – the Station Commander. After talking to a number of ground crews and watching Stirlings being ‘bombed up’, the Royal party then sampled the delights of the officer’s mess before departing the airfield on their tour.

In September 1942, a signal came through to RAF Marham that would not only affect its future but would also be a significant step forward for RAF Downham Market. The order was to separate ownership of the two airfields; Marham transferring to 2 Group, whilst Downham Market would stay, “as a separate entity” in 3 Group with only the control of rations, pay and equipment remaining with Marham. So, during the autumn of 1942, Downham Market became an independent airfield operating within 3 Group.

The new year saw further changes at Downham Market as 218 Squadron began replacing their Stirling MK.Is with the upgraded MK.IIIs – the last model of the Stirling bomber before they were relegated to other duties. By June, the last of the MK.Is were gone, and although fitted with better engines, the MK.III remained limited by both its short wingspan, weak undercarriage and poorly designed bomb-bay.

The Short Stirling, the first of the heavies for Bomber Command, was liked by many of its crews, but its shortcomings were to become all too apparent, all too soon. One of its problems was its enormous height, created through its huge, weak undercarriage, which often made landings difficult, especially for the unwary. Another recurring problem was a significant swing to port when taking off, and when combined, these two features created a difficult aeroplane to control even at the best of times, let alone when badly damaged or in very poor weather.

One of several casualties at Downham Market occurred on the morning of May 14th, 1943, when Stirling ‘BF480’ HA-I piloted by Sgt. W. Carney, swung on touchdown, causing it to career off the runway into the Watch Office. No injuries were sustained by those onboard the aircraft, but two other crewmen (Sgt. A. Denzey and Sgt H. Lancaster) who were on the ground having previously landed, were killed in the accident. Coincidentally to this, a second 218 Sqn Stirling, ‘EF367’, HA-G had a similar landing away at RAF Chedburgh at the same time on the same night. Onboard that aircraft were both a Canadian and a New Zealander, and here, all but two of the crewmen were killed, the others escaping with injuries.

The FIDO Fog Dispersal System

In March, a major decision was made to install the still experimental FIDO (Fog Investigation and Dispersal Operation) fog dispersal system here at Downham Market. Following in the footsteps of RAF Graveley, the benefits of this system would very quickly bear fruits. Despite this however, only fifteen British airfields were to ever have the system fitted.

The last remnants of the main runway. Sadly, this has now also been removed. It was this runway that utilised FIDO.

FIDO was an ingenious system designed to combat one of aviation’s greatest hazards – fog. It worked by burning fuel through a network of pipes laid parallel to the runway, producing an intense heat that dispersed the fog and cleared a visible path for landing / departing aircraft. This innovation gave airfields a crucial advantage, allowing pilots to land – and take off – safely in conditions that would otherwise have forced them to divert or attempt dangerous approaches.

These pipes, or burners, were supplied from large storage tanks, which in Downham Market’s case, were located to the south-east of the airfield just off the main site. Each tank was filled by road tankers travelling from Kings Lynn some ten miles north, five tankers carrying out two runs each to complete the fill. Oil from these tanks, was then fed into the system – which was installed along the main east-west runway – by large pumps. Once lit, the burners could clear extensive fog or mist in a relatively short period of time. This main storage tank site is today a car dealership, all signs of the network of pipes having since been removed.

The installation of the FIDO system at Downham Market progressed slowly at first, initially covering only the touchdown zone and the first 700 yards of the main runway on an east–west alignment. As time progressed though, this would be extended to almost the entire length of the main runway.

As FIDO continued to be developed, each new burner type brought both promise and challenge. The system began with the Mk.III, or “Haigill,” whose early trials revealed both its potential and its limitations. Engineers and ground crews worked tirelessly to refine the design, and it was soon replaced by the improved Mk.IV. By the time the Mk.V was introduced, labour had become more readily available, allowing crews to deploy it to a greater capacity. This final iteration proved far more robust, capable of withstanding sustained use while producing a steady, reliable flame – a vital lifeline for pilots navigating the foggy skies. Each upgrade was not merely a technical improvement, but a testament to the determination and skill of the teams who kept the airfield operational under the most challenging conditions.

But it wouldn’t be until late 1943/44, that this longer section of the system was installed, now extending to 1,362 yds, almost the entire length of the main runway. The main problem with any FIDO installation was always where the runways crossed, aircraft could damage the pipes leading to potentially serious accidents if they did. The solution was to place the pipes below ground level, along a gutter at these points, thus avoiding any potential damage from heavy aircraft running across them.

However, where the burners were set above ground level, and even though they were fifty feet from the runway’s edge, accidents were inevitable, and some aircraft did manage to damage the piping and on more than one occasion resulting in serious setbacks.

Following experimental lighting and landings in the autumn of 1943, the first official use of the system, was on the night of December 16th/17th that year, when a large number of aircraft returning from Berlin were diverted to Downham Market due to their own bases being fog bound.

Over thirty-five aircraft landed at Downham Market that night, fifteen of Downham Market’s own aircraft along with several ‘cuckoos’ from other bases unable to land at home. The toll on crews had FIDO not been in existence, most certainly being considerably higher than the terrible price that had already been paid on that disastrous night over Germany. FIDO with all its counter arguments, had proved its worth in one fell swoop.

With little use of FIDO for another year, Downham Market would once again be the saviour of the skies, when the autumn of 1944 turned to winter. The offensive in the Ardennes came to a standstill, little flying could take place, and the weather had turned extremely cold, foggy with heavy snowfalls across Europe.

On Christmas Eve, 1944, 635 Squadron were tasked with a raid to Dusseldorf (then called Lohausen) take off at 12:28. Thick fog prevailed, and it was only by using FIDO that any aircraft were able to depart Downham Market at all. The burners were lit in under twelve minutes, and all thirteen aircraft were able to depart. Some three hours later, the burners were lit again and the Lancasters began returning all eventually landing safely. Mixed in with them were not only two departing Mosquitoes, but more ‘cuckoos’ including three Lancasters, two Dakotas, a B-17 and a Noresman. *11

By the time FIDO was dismantled in September 1945, there had been somewhere in the region of 220 movements in and out of Downham Market using the system, burning a massive 2,145,000 gallons of petrol and saving countless lives and aircraft.

With plans for the invasion of occupied Europe well in hand by mid-1943, movements across Britain were starting to take place. At Downham Market

number of hangars were used to store around twenty-six Horsa gliders (hence the large number of hangars on site) ready for the invasion whenever it may have come. Between April 1943 and March 1944, the airfield was awash with such stored examples. Accompanying the gliders were No. 14 Heavy Glider Maintenance Section, who maintained and prepared the gliders ready for when they were needed.

As D-Day approached, the gliders were removed and taken to their departure airfields across the country. One of these managed to become detached from its tow aircraft and crashed into a local field at Stradsett.

In August 1943, ‘C’ Flight of 218 Sqn was extracted to create a new squadron, 623 Sqn, using the MK.III Stirlings already on site. On the very day they were formed, 10th August 1943, four crews were briefed for operations – the target Nuremberg. Unfortunately, once over the target, crews had difficulty in distinguishing any relevant ground detail, and as a result, bombs were scattered over a wide area, and the operation was largely unsuccessful. Thankfully though, with little enemy opposition, all aircraft returned to Downham Market safely.

Acts of Bravery

ever, two days after this on the night of August 12th/13th 1943, it was a different matter. It was whilst flying a 218 Sqn Stirling over Turin, that Flight Sergeant Arthur Louis Aaron, would suffer bullet strikes to his head that would break his jaw and tear away a large part of his face. Further bullets damaged his lung and right arm rendering it completely useless. Aaron still fought on though, and despite his severe injuries, he managed to assist the bomb-aimer in flying the stricken Stirling away from the enemy. Unable to speak, he communicated instructions to his bomb-aimer by writing with his left hand.

Determined to bring the aircraft down safely, Aaron attempted on no less than four occasions to land the aircraft himself, before eventually, and with failing strength, he was persuaded to vacate the cockpit: enabling the bomb-aimer to bring the Stirling down completing a belly landing on the fifth attempt. Aaron later died from exhaustion, the consequence of his determination and unparalleled allegiance to his crew, his aircraft and his duty. He would be the first of two Downham Market pilots to receive the Victoria Cross – an award only ever given for extreme bravery in the face of the enemy.

The new squadron 623 Sqn, like so many other squadrons, however, was to be a short lived one. With high demand for Stirlings in the Conversion Units, it was decided to utilise the aircraft of 623 Sqn for this role, and on December 6th, 1943, the unit was officially disbanded. Some crews made the return to 218 Sqn, but many others were posted out to new units. In their short four months they would fly a total of 150 sorties, losing ten aircraft in the process – a loss rate of some 7%.

The void left by 623 Sqn would be soon filled though. Just four days later another squadron would transfer in, that of 214 (Federated Malay States) Sqn from RAF Chedburgh also flying the Stirling MK.III. For the majority of December, 214 Sqn would carry out ‘gardening’ missions, dropping mines designated ‘Nectarines‘ or ‘Cinnamon‘ in ocean waters along known German shipping routes. Other operations would see bombs dropped on ‘Special Targets‘ although the Operational Record Books don’t specify the identity or nature, of these targets.

214 Sqn as with 623 Sqn, would be another of these short stay units, on January 17th, 1944, elements of the unit would transfer to RAF Sculthorpe and the new 100 Group, for RCM (electronic warfare) duties taking on a new aircraft, the American B-17 ‘Flying Fortress’ or Fortress I. As crews carried out circuits, lectures and training at RAF Sculthorpe, the remainder of the squadron would continue flying operations from Downham Market. Gradually though, crews continued to transfer over, and by the 24th January, all personnel had transferred over leaving Downham Market far behind them.

In March 1944, Downham Market’s long-standing unit, 218 Sqn, was finally ordered out, and on the 7th the entire squadron departed, the operations books simply stating: “218 Sqn moved from Downham Market to Woolfox Lodge by road and air today“. *2 Once at Woolfox Lodge, they too would begin disposing of their Stirlings taking on the RAF’s new heavy bomber – the Avro Lancaster.

The dust wasn’t allowed to settle at Downham Market however, and before long more personnel and a new squadron would arrive, ready to fill the skies of Norfolk. This was no ordinary squadron though. With concerns about the poor quality of bombing and the lack of accuracy, it was decided to form a new Group, one that went very much against the wishes of Arthur Harris. Seen as ‘elitist’, Harris vehemently disagreed with the decision and so fought his corner bravely. But with little choice in the matter, and lacking his own high-level support, he eventually succumbed to the Air Ministry’s demands, putting in command the Australian Group Captain, Donald C.T Bennett, CB, CBE, DSO.

Arrival of The Pathfinders

The new group would be the reborn 8 Group, now called ‘The Pathfinders’ (PFF), and was designed to use the cream of Bomber Command crews whose record for bombing accuracy had been excellent. Aircraft from the Group were to fly ahead of the main bomber force and ‘mark’ the target by various means – coloured flares being the primary and main method. In principle it worked well, but as records show, it was not without its own difficulties or indeed its setbacks.

Bennett, an aggressive pilot who didn’t suffer fools gladly, quickly won the admiration of his crews. He was also highly admired by Harris, who once described him as the “most efficient airman” he had ever met; Harris considered Bennett perfect for the role. In appointing him though, Harris had dismissed all other possible candidates including and especially, Air Chief Marshall Basil Embry – the Air Ministry’s favourite for the position.

The Pathfinders were officially formed on 15th August, 1942, with 8 Group coming into formation in January 1943. With the formation of the new Squadron, 635 Sqn, in March 1944, Downham would now be playing its part in this role.

Formed out of elements of both 35 and 97 Squadrons, the new unit would also mean a change in aircraft type at this Norfolk airfield, out went the now relegated Stirlings and in came Avro’s remarkable four-engined heavy, the Lancaster MK.III.

635 Sqn was created under the command of Wing Commander Alan George Seymour Cousens on March 20th, 1944, using ‘C’ Flight from RAF Graveley’s 35 Sqn and ‘C’ Flight from RAF Bourn’s 97 Sqn. A total of eight aircraft and crews from each flight immediately began the move over to Downham Market. At 09:15 hrs the first of the road crews arrived from Bourn, with further sporadic arrivals until 11:00 hrs. The first aircraft to arrive touched down at 12:00 hrs, and within the next twenty minutes all aircraft were safely on the ground. Graveley crews began arriving soon after this, their first aircraft, along with a ground party, arriving at 15:05 hrs.

The new squadron consisted of 36 Officers, 120 NCOs and 200 ‘other ranks’. They were accommodated in Site ‘J’ whilst 20 NCOs and 40 armourers were accommodated in site ‘B’. A small number of officers were put up in the Rectory just outside the main gate of the airfield*3.

Shortly after the crews had landed, they were quickly briefed for an operation to attack Munich, but by the time the aircraft were prepared and bombs loaded, the operation had been cancelled. Now with time on their hands, the crews were stood down and given the chance to settle into their new homes.

635 Sqn would continue to use the Mk.III Lancaster for the next four months, replacing it with the Lancaster MK.VI from March onward. This was an unusual model of the famous aircraft as it had neither a nose nor mid-upper turret, instead it was crammed with electronic radar jamming devices. Also replacing the normal three-bladed propellers were four bladed examples, aiming to improve the aircraft’s already outstanding performance.

March 1944 would see other big changes at Downham Market, with the appointing of a new Station Commander – Air Chief Marshal Sir Wallace Kyle, who had previously been in command at RAF Marham a few miles away.

An Australian born National, his RAF career began at RAF Cranwell in 1928 as a Flight Cadet with ‘B’ Squadron, before flying with various units including the Fleet Air Arm.

His daring and bravery led him to being awarded the DFC in April 1941 as Officer Commanding 139 Squadron where he led an attack on Ijmuiden steel works dropping his bombs from a mere 50 feet after both intense flak and fighter attacks had tried to prevent him from doing so.

His award citation stated “…his resolute determination and leadership have been largely responsible for the high standard of efficiency in his squadron“.

Post war, he would be posted to HQ in the Middle East Air Force, and Malaya as Air Officer Commanding (AOC). In the 1960s, he would become AOC of Bomber Command remaining in post when it transitioned to Strike Command in 1968.

After leaving the service, he became Governor of Western Australia, and on his death, his widow named the RAF’s Benevolent Fund’s Princess Marina House in Sussex, after him, designating it the ‘Kyle Wing’.

A long and distinguished career he would see Downham Market through a large part of the war before transferring himself, to Bomber Command Headquarters on October 9th, 1944.

The Mosquito Lands

A growth in aircraft numbers and the development of Pathfinder methods soon led to a new branch of the Group, the Light Night Striking Force (LNSF) equipped with de Havilland’s ‘Wooden Wonder‘ the Mosquito. In response to this, 571 Sqn, a new light bomber squadron equipped with the Mosquito XVI, was born here at Downham Market on April 5th 1944, barely two weeks after 635 Sqn themselves arrived.

The squadron was formed under War Establishment LWE/BC/3357 and called for 174 personnel including a Wing Commander, four Flight Lieutenants, two Squadron Leaders and a mix of other ranks including eighty-three Aircraftsman and seven WAAFs.

As a temporary measure however, it was decided that on April 10th, the squadron would be reduced to one Flight instead of two, leaving eight aircraft plus a ‘spare’ at Downham Market whilst the remainder transferred to RAF Graveley. The idea behind the move was two-fold, firstly to bolster the expansion of 105 Sqn at Graveley, and secondly, to provide experience for the ground crews on the Mosquito. The new (acting) Wing Commander, J. M. Birkin AFC, would control both flights but would be based at Graveley.

Two days after the decision, the first three Mosquito aircraft arrived at Downham Market: ML935, ML942 and ML963 all with the Merlin XVI 72/73 engines.

The move went well, but on the 17th, a new order would come through that would change Downham Market yet again.

Movement order 21 required the entire 571 Squadron to transfer to RAF Oakington, effective by 24th April. With that, preparations began, and the advanced party moved from Downham Market on the 22nd followed by the rear party on the 24th. The entire squadron including the Graveley detachment were, by the end of the day, then at Oakington. Due to their very short time here and subsequent move, there were only twelve operations flown by the squadron during this short period of their history – all from RAF Graveley.

571’s departure left 635 Sqn as the only operational squadron at Downham Market. Whilst somewhat quieter, it was not to be all plane sailing.

In the early hours of June 4th 1944*6, the peace around the airfield was suddenly and horrendously shattered, when Lancaster ND841 ‘F2-D‘ piloted by F.O. George. A. Young (s/n: 134149) RAFVR 635 Squadron, suddenly developed a swing as it ran at speed down the runway.

Initially, the aircraft and crew, were designated for training, but that night, nine aircraft along with their crews, were suddenly detailed for operations to Calais, including F.O. Young’s crew in ‘D-Dog’. They were given orders to mark a coastal defence battery, as part of the preparations for the forthcoming D-Day invasion.

The mission would involve 127 Lancasters and 8 Mosquitoes of 1, 3 and 8 Groups, and targets would include gun batteries at both Calais and Wimereux. The operation was a diversionary raid as part of Operation “Fortitude South“, the elaborate plan to fool the Germans into believing the invasion would occur in the Pas-de-Calais region rather than Normandy.

At 28 minutes past midnight, F.O. Young lined the Lancaster up on the runway, opened the throttles and began the long run down. As the Lancaster approached take off, it began to swing, violently striking the roof of the B1 Hangar. In an uncontrollable state the aircraft crashed and exploded in a massive fireball just outside of the airfield, killing all those on board. What was left of the Lancaster was later salvaged, and three of the crew buried in the local cemetery in Downham Market.

Two months later, another pilot of 635 Sqn, also flying a Lancaster III, ND811, ‘F2-T’, Squadron Leader Ian Bazalgette, would be awarded the second of Downham Market’s Victoria Crosses.

On August 4th, 1944, flying Lancaster ‘T’ for Tommy, on a daylight raid to mark the V1 storage depot at Trossy St. Maximin, the aircraft was hit by flak knocking out both starboard engines and setting the aircraft on fire. Determined to get the job done, Bazalgette pressed on, marked the target and then instructed the crew to bail out. However, two of them were so badly injured that they could not do so, and so Bazalgette attempted to bring the aircraft down in a controlled crash landing. Unfortunately, on impact with the ground, it exploded, and the resultant explosion killed all three remaining crew members on board.

For his bravery and sacrifice, Ian Bazalgette was also awarded the V.C., the highest honour for military personnel. The London Gazette, of 14th August 1945, announced the award, citing: “His heroic sacrifice marked the climax of a long career of operations against the enemy. He always chose the more dangerous and exacting roles. His courage and devotion to duty were beyond praise“.

Bennett meanwhile, had a policy of operating both a Mosquito and Lancaster squadron at each of his airfields, but with the loss of 571 Sqn to Oakington in April, it meant Downham Market was one short. To remedy the situation, during that same month, August 1944, he formed another squadron here at Downham Market. Joining 635 Sqn were 608 Sqn, who had previously been operating abroad before being disbanded. They were reformed here on August 1st that year (1944), joining Bennett’s elite Pathfinder group.

Their formation bolstered both the number of aircraft and the number of personnel present here at Downham Market. Flying the Mosquito XX, XXV and eventually XVI, they remained at the airfield for a year whereupon they were once more disbanded. Whilst operating these aircraft, 608 Sqn would fly 1,726 operational sorties all as part of Bennett’s Pathfinder Force.

608 Sqn were a Royal Auxiliary Air Force Squadron, initially formed on 17th March, 1930 as 608 (North Riding) Squadron at Thornaby before the station was even built. The squadron went through a number of changes during these early years, but flying began with Avro 504Ns and Westland Wapitis as a bomber squadron.

Following the outbreak of war, 608 Sqn performed their first operational flight taking reconnaissance photos of possible targets. Their transition to Downham Market took several years, but one notable event was the arrival of the Blackburn Botha, the first Blackburn aircraft to equip land-based squadrons since 1918.*5

After spending time in the Middle East supporting the war in Italy, and performing Air-Sea rescue duties, they were disbanded at Pomigliano with crews being spread across four other squadrons. Then, on August 1st, 1944, they were reactivated in the UK with Mosquitoes under Donald Bennett and the Pathfinders.

608 Sqn’s primary role was to carry out night strikes as part of the Pathfinder Operations focusing on the German heartland. Targets included: Berlin (almost nightly), Frankfurt, Hanover, Essen, Stuttgart, Nuremberg, Hamburg, Emden and Kiel. Their first operational sortie from Downham Market was on the night of 5th / 6th August 1944, when a single Mosquito took off and bombed Wanne-Eickel.

They settled into their routines very quickly, but in October, things would go wrong for the new squadron. On each night of the 9th, 10th and 11th, a Mosquito was lost with only two of the three crews surviving. One of those aircraft was shot down over Berlin, whilst the other two were lost within a stone’s throw of the airfield; one crashing into a cow shed, for no explicable reason – killing both men – and the other suffering engine failure just after take-off, causing it to crash-land, without injury, in a field nearby. Their full story can be found in ‘9th October 1944, loss of Mosquito KB261‘

This terrible chain of events was followed with another incident only a month later, when, on the night of 6th November 1944 twelve aircraft from 608 Sqn took off in a diversionary attack on targets at Gelsenkirchen. The idea was to draw defences away from a much larger force attacking both Gravenhorst and Koblenz. The plan was for 608 to begin their attack five minutes ahead of the other forces, a plan that went like clockwork. However, it would not go well for one Mosquito, that of Pt. Off. McLean and Sgt. Tansley.

The full story of Mosquito KB364, piloted by Pt. Off. James McLean (26) and Sgt. Mervyn Lambert Tansley (21), appears in Heroic Tales, but this was to be their final, fatal flight.

On return, the aircraft careered into All Saints’ Church, Bawdeswell, some 30 miles north-east of the airfield, setting it alight. The impact was such that parts of the aircraft struck two other homes, causing extensive damage to both properties. The resultant fire took four hours to extinguish and included crews from other nearby airfields. In honour of the two airmen, a plaque manufactured from part of the Mosquito has been mounted on the church wall inside the building.

On a brighter note, November 1944 marked the beginning of a flurry of commendations, with the first Distinguished Flying Cross being awarded to Flight Officer N. Wilkinson. As the year turned, and 1945 dawned, the recognition of courage continued, and in January seven more awards were announced – testament to the steadfast bravery of those who served during those final, gruelling months of the war.

The Christmas of 1944 – 45 brought no respite for those stationed at Downham Market, particularly for the FIDO crews. Freezing fog, snow, and persistent poor weather created havoc both on the Continent and at home, grounding aircraft and testing patience and skill alike. FIDO, designed primarily as a landing aid, also made it possible for aircraft to take off in near-zero visibility – but reaching the runway could be just as perilous as the flight itself. On nights when the fog lay thick across the airfield, visibility shrank to only a few feet. Ground crews would stand alongside the perimeter tracks, torches in hand, guiding the bombers cautiously toward the runway. For any pilot who strayed too far from that narrow path, the danger was real – one wrong move could see an aircraft sink into the soft ground, or worse.

But by the dawn of 1945 the war in Europe was all but over. Operations began to focus on eliminating troop concentrations, possible German escape routes and docks harbouring enemy ships. Both 635 and 608 Sqns continued flying operationally until the war’s end. These were followed by ‘Cooks’ tours, crews flying ground staff over to the continent to see the immense damage inflicted upon the German cities.

Eventually, in August and early September these last two operational squadrons at Downham Market were disbanded, 608 Sqn on August 24th and 635 Sqn on September 1st. This left Downham Market devoid of all front-line units.

Before their departure, 608 Sqn saw the giving of further awards: firstly, a bar to the DSO of Wing Commander Alabaster DSO. DFC & Bar, followed by a DSO to Flt. Lt. R.J. Cook DFC, DFM. Both these airmen having been in the pre-war Volunteer Reserves (RAFVR) and Alabaster having flown over 100 operational sorties.

A recently discovered photograph showing a D.H. Mosquito of Downham Market, taken on May 2nd 1945. It was taken just prior to the last mission undertaken by RAF aircraft on an attack on the Kiel Canal. It shows Ground & Aircrew next to their Mosquito and ‘Cookie’. It was found by Brian Emsley, his father Edward Emsley is far left.*8

Now much quieter, the airfield was passed to 42 Group, who used it as a satellite for their 274 Maintenance Unit, who stored unwanted Mosquitoes ready for disposal.

With peace now settling across Europe, focus turned to returning personnel back to ‘Civvy street’. Within Bomber Command, a new scheme was set up, and personnel were encouraged to make good use of it. Across the range of Pathfinder stations, EVT (Educational and Vocational Training) was introduced. These classes were designed to give personnel much-needed skills in a range of civilian areas, helping them integrate back into civilian life. Classes were broad and included a range of domestic activities such as: landscape gardening, cookery, music and carpentry. Some of these such as ‘domestic science’ were designed particularly with the WAAFs in mind, whilst others were geared more (but not exclusively) toward the men.

1945 – Landscape and floral gardening are subjects given in the E.V.T. classes at Downham Market. Leading Aircraftman Arthur Pickersgill [centre] is now the station instructor. (IWM CH16028)

Postwar Use and Cold War Years

For the next two years the accommodation huts would be used as a Land Army Hostel, before, in 1949, the council took them over for much needed civilian accommodation for displaced persons. Midway through this change, in 1948, aviation returned somewhat briefly, when the airfield was used for night Helicopter flight trials by BEA – a civil air company – transporting mail using Sikorsky S-51 Helicopters. This was also a short-lived venture but was by the end, considered a very successful companion to the daytime routes recently started between Peterborough and a number of towns between Kings Lynn and Norwich. The venture included installing a flashing Sodium Beacon at Downham Market, its precise location on the airfield is not known and it may well have been a mobile unit*4.

On October 13th, 1951, part of the airstrip was once again used for flying, this time by Norfolk Airways, who flew Autocrats (G-AIRA and G-AJAR) and Auster 5 (G-AJYB) as pleasure flights. Another short-term venture, it wasn’t to be the last aviation use of the site, even though in 1957, the land was sold off. At this point, the airfield was primarily returned to agriculture, the airfield being dug up and ploughed for crops, leaving only a few buildings and the airfield’s runways intact.

In the post war years, tensions between the East and West became more fragile and it was during this ‘Cold War’, that a 270-foot tall steel lattice tower was erected on the eastern end of the former technical site as part of the wider network of post-war communications and early warning infrastructure that supported the RAF and the UK’s national defence system. Local accounts suggest it went up around 1950 and was connected to regional relay routes serving stations such as RAF Marham and RAF Feltwell, linking ultimately to the early warning centre at RAF Fylingdales.

Built to last (local memory suggests it was built to “a very high specification” – blast-resistant foundations, heavy steelwork, with a secure communications buildings at its base) and visible for miles across the landscape, it became a familiar landmark for the residents of Downham Market; known simply as “the Bexwell mast”, eventually it became a curiosity left over from “the RAF’s residency”. The tower continued to be in use for several decades, later serving civilian telecommunications under the Post Office, then British Telecom and finally Arqiva. After approximately sixty years of service it was finally brought down – around March 2009 – its crumpled remains laid out across the industrial yard before its final removal.

The communications mast being dismantled, March 2009. (Photographer unknown via Downham Market Heritage Centre).

Following the addition of the mast, in the 1970s, crop sprayers of Fisons Test Control (later Fisons Airwork) used the site flying a range of aircraft including Hiller UH-12s and Auster J/INs; as did Agricultural Aviation with Tiger Moths; Farmair, Management Aviation, Farm Aviation and A.D.S. (Aerial). These companies provided a wide range of aircraft predominately Pipers using a short section of the western part of the main runway.

An edited picture of Downham Market airfield dated Nov 1963. Note the mast location to the east of the airfield and the runway section used for crop spraying.*9

Flying small, light aircraft in the vicinity of a military low fly zone (RAF Marham was still very much in operation) was a hazardous role. On August 9th, 1974, a Piper PA-25 (G-ASVX) and Phantom (XV493) from RAF Coningsby collided at Fordham Fen, 2.4 nm south of Downham Market.

The official Air Accidents Investigation Branch report (Department of Trade, 1975)*7 highlighted how the two aircraft were flying at right angles to each other at a height of 300 feet. It states that neither pilot saw the other aircraft in time to react or take evasive action and so collided killing all three on board the two aircraft.

The Phantom, an FGR 2, from RAF Coningsby, was being flown by an experienced crew and was on a low-level navigation exercise at the time. The Piper, also flown by an experienced pilot, had completed his crop spraying exercise and was returning to replenish his load when the accident happened. Both aircraft were destroyed in the collision.

Decline and Legacy

Downham Market’s days as an airfield soon drew to a close when plans were laid for a new bypass around the growing town. Hardcore was needed for the road’s construction, and the abandoned runways offered a convenient source of material. One by one, all three runways were quarried away, along with much of the perimeter track, leaving only narrow strips wide enough for farm traffic. Only a small section along the western edge survived to full width.

Many of the wartime buildings remained though, and in time small, local businesses found new uses for them. The former technical site became a council storage area, and the old guardroom was converted into a bespoke kitchen showroom – within which a few artefacts from the station’s past are still stored, quiet reminders of the site’s wartime purpose.

The Official Sales Document for the TA Centre and Married Quarters of RAF Downham Market. (Downham Market Heritage Centre_

The TA Centre and the former married quarters were also sold off, later occupied by a local Territorial Army group who continued to use the premises for training. Both stand today beside the main road that once marked the airfield’s boundary.

Now, little remains of what was once a bustling wartime station. The runways – long since lifted and repurposed for the A10 – have erased almost all trace of the airfield itself. Yet across the former technical site and scattered accommodation areas, a handful of original buildings endure, serving farmers and small industries. Their weathered walls stand as silent witnesses to a place that once echoed with the sound of engines, and to the men and women who served there.

The post-war radio mast, demolished many years ago, has been replaced by two modern masts that still operate at the western edge of the former airfield. Used as communication transmitters, they stand as quiet sentinels – reminders of the site’s enduring connection to communications, long after the roar of wartime bombers faded into history.

For those who know where to look, the landscape still whispers its secrets. With a discerning eye and an understanding of wartime airfield layouts, it is possible to detect the ghostly outline of the station. Crumbling huts, overgrown by trees and brambles, peer out from the undergrowth. Time, however, is taking its toll: the cracked brickwork and broken windows tell a story of gradual decay, a slow erasure of what was once a thriving centre of activity.

The main runway that once stretched from east to west – a vital artery in the airfield’s wartime operations – retained a small section that served the local farmer long after flying had ceased. In the early 2000s, even that final remnant was removed, erasing one of the last tangible links to the station’s operational past. It was along this runway that the FIDO system once blazed through the mist, guiding bombers safely home. Today, the site where its fuel was stored is occupied by a modern car dealership – a quiet, everyday presence standing upon ground that once glowed with the fires of war.

A flooded Battle Headquarters. Several rooms exist below ground level, but these are all flooded, some said to be very deep.

Part of the western perimeter track still exists, stretching from the threshold of the second runway almost to the northern end of the third, though the A10 now cuts across it, removing the uppermost section. A reinstated public track – formerly the Wimbotsham to Crimplesham road, closed during the war – now crosses the northern end of the airfield. It is here that the flooded remains of the Battle Headquarters can be found, hidden within a ditch beside the public path. Its roof now forms a rough bridge into an adjoining field, a faint reminder of the command centre that would have once directed operations if attacked.

Much of the northern section of the perimeter track can still be walked, curving eastward toward where the main runway once lay. Along the way, a side track leads to the former bomb store – now private land and an overgrown woodland. Nearby stands the ultra-heavy fusing point, today used as a farm shed. At the far end of the track lies the former accommodation area once built for FIDO personnel, their huts – constructed by Laing – long since gone. Across the road stands the modern car dealership, occupying what was once the heart of the FIDO installation. Here, the perimeter track broadens once again, turning east toward the old technical area.

Across from this technical site lies Bexwell – a small hamlet of houses and a church. Near the old camp entrance stands a memorial dedicated to two of the airfield’s most courageous airmen: Aaron and Bazalgette, both awarded the Victoria Cross for their bravery. The road beside the memorial once led to the wartime accommodation sites. The first of these was the WAAF camp, one of only two surviving areas where original buildings still remain.

Other nearby sites included Communal Site No. 1, Dormitory Site 1 (A), the Sick Quarters, and Dormitory Sites 2 (B), 3 (C), 4 (K), and 5 (J). A track from here leads to one of the old sewage works, eventually re-joining the A10. Across the main road lies Communal Site No. 2 – the second area where the wartime hospital and mortuary still survive, now used by an engineering firm. Hidden among the bushes nearby is a small First World War memorial, a poignant reminder that this land’s connection to service and sacrifice stretches far beyond the Second World War.

A pathway beside these buildings leads to another sewage treatment site, visible through the trees from the main road into Downham Market. All stark reminders of a once hectic airfield that led the fight against the Nazi tyranny of World War 2.

Downham Market airfield has a remarkable history – its story is one of courage, endurance, and sacrifice. Yet what remains of this historic site is steadily succumbing to neglect and decay.

The skies above are still filled with the sound of aircraft. Modern F-35s from nearby RAF Marham – the most advanced fighters in the Royal Air Force – often pass overhead. When I first visited, it was two Tornadoes that broke the quiet as I stood reading the dedications to Bazalgette and Aaron. It felt a fitting tribute – not only to those two brave pilots, but to all who served here, at a station built as a satellite for the very same airfield from which those Tornadoes flew.

In 2015, a £170 million regeneration plan was announced, suggesting that Downham Market’s wartime airfield might soon be lost to development. Further details were expected in 2016, but by early 2020 the funding appeared to have been withdrawn. Nothing more has since been said. More recently, a fast-food outlet and coffee shop have been built along the southern edge of the old perimeter – a far cry from the roar of Lancasters and Mosquitos that once filled these skies.

In April 2017, a fundraising project, highlighted on the Eastern Daily Press website, was launched to create a seven-slab memorial near the site of Dormitory Site 1, beside the A10. The goal was to raise around £250,000 to commemorate those who flew and fell while serving at RAF Downham Market. Though details are uncertain, the project ceased and never came to fruition.

Further change did come in May 2023 when housing development began along the western perimeter, removing much of what little remained of the track. It was yet another blow for this remarkable place.

On a more positive note, later that year, construction began on a new memorial, positioned near the end of the main runway close to the old FIDO installation – a final act of remembrance for those who served. According to the creator’s website, it is to be dedicated in May 2026.

Downham Market may now be changing beyond recognition, but the memory of its airfield – and the bravery of the men and women who once called it home – endures. Whatever becomes of the land itself, their legacy continues to echo across the fields and skies of West Norfolk.

The trail now leaves Downham Market heading east towards Norwich. Before stopping off at RAF Marham however, we pass through the Norfolk countryside and a secret that shall no doubt, forever remain just that.

RAF Barton Bendish

On leaving Downham Market, travel East toward the A47 and Norwich. A few miles along the road, to the south, is the village of Barton Bendish.

Recorded in the Doomsday book as Bertuna, it once boasted three churches, only two of which survive today, which was remarkable considering the small size of the parish.

During the Second World War however, a field to the south of the village suddenly became a hive of activity, when it was developed into a landing ground under the designation XIBB*3.

The reason for this activity, was that at the outbreak of war, orders were issued to all airfields across the UK to implement the ‘Scatter’ directive, a plan to relocate aircraft at various satellite airfields to disperse them away from the main airfield and possible German attack. This meant that many squadrons were spread over several airfields for short periods of time until the immediate threat, or perceived threat, had subsided.

This was first seen at Barton Bendish (a satellite of Marham) on September 2nd 1939, when XIBB, or Eastmoor Landing Ground as it was later known, became ‘operational’.

The site chosen was on land between 10 and 25 metres above mean sea level on a slope with the lower end of the slope at the 10 m height and the upper end at 25 m.

The whole site, which covered approximately 340 acres, was grass, with no permanent buildings on site. A small number of ‘pill boxes’ were built as defensive structures along with a mobile pill box known as a ‘Bison mobile Pillbox’ placed on the back of a truck.

In 1939, Hurricanes from RAF Sutton Bridge were placed here temporarily, but more common were the Wellingtons of 115 Sqn located at nearby RAF Marham. With no cover, the protection Barton Bendish offered seemed small in comparison to the main airfield at Marham. Although there were no hangars at Barton Bendish, it is recorded that aircraft were parked under trees on two official dispersals near to a property called Field Barn.

The openness and cold of Barton Bendish has been noted in several scripts, and this caused problems in the winter months when starting cold engines. ‘Johnnie’ Johnson recalls in Martin Bowman’s book “The Wellington Bomber“*1 how they had to start the Wellington’s engine by getting it to backfire into the carburettor thus igniting unspent fuel in the air intake. This was then allowed to burn for a few seconds warming the carburettor allowing the engine to start. Careful timing was paramount, the danger being that the aircraft could catch fire if you were not cautious!

It was not long after this initial directive, on Sunday 5 November 1939, that another Marham Wellington, this time L4239 from 38 Sqn, who were also using Barton Bendish as their Relief Landing Ground, took off on return to Marham only to strike a tree whilst carrying out a low flying manoeuvre. The aircraft, crashed at Marks Farm, Boughton, four miles south of Marham airfield, after it caught an oak tree tearing off part of the tail plane. All seven crew were killed that day despite the efforts of local service men, who were playing in a nearby football match, failed to help them*2.

In the early part of the war, not only was Barton Bendish used as a relief landing ground but also as a decoy site, a flare path being lit at night to attract enemy bombers away from Marham a few miles down the road. How effective this was, is not known, but it may well have saved one or two lives at the main airfield.

Also during 1941, 26 Squadron (RAF) flying Tomahawk IIs were stationed here for three days from the 27th – 30th September, as was 268 Squadron on several other occasions. Also flying Tomahawk IIs, they passed through here during May 1941, then again between the 21st and 25th June 1941, 28th and 30th September 1941 and then again on the 25th/26th October 1941. No. 268 Sqn who were then based at RAF Snailwell, used the airfield as ‘the enemy’ in a station defence exercise, whereby they would perform mock attacks on Snailwell using gas, parachute and low flying strafing attacks methods. Being little more than a field, Barton Bendish provided no accommodation for the visitors, and so the aircrews slept in tents overnight, these being removed the next day after the attacks had been made.

Whilst the airfield was being utilised in this manner, it also witnessed another crash which resulted in the loss of all on board. The aircraft, Hampden X2917, was on operations from Waddington in Lincolnshire when it encountered poor weather and had to return home. Unfortunately, whilst also at low level it too clipped trees causing it to crash on the perimeter of Barton Bendish / Eastmoor landing ground. The four crew: Sgt Gordon Stephenson Bradbury (pilot); Sgt William Joseph McQuade (observer); Sgt. David Hinton Howe (wireless operator) and F/Sgt. Samuel David Yeomans (wireless operator), were all killed in the subsequent crash.

By 1942, the Stirling was becoming a predominant feature at Marham, and with Barton Bendish being too small for its required take off distance, Downham Market became the preferred satellite, Barton Bendish being side-lined for other minor uses – primarily fighter or Army Liaison flights.

On January 2nd 1945, the area resonated once again with the sound of a crashing aircraft, when B-17 #42-32112 of the 337th BS/96th BG based at Snetterton Heath crashed whilst forming up over Beachamwell a stone’s throw east of Barton Bendish. The aircraft, a Boeing B-17G-35-BO, had previously been involved in a mid air collision in October 1944 with another B-17G #44-6137 and a P-47D Thunderbolt #42-25690, and had been utilised by United Airlines. As a result of this crash, there were nine fatalities: the pilot Joe Miller, Co-pilot: Jim Thoeness, Navigator: Bob Drum, Togglier: Ray Freidmann, Flight engineer/top turret gunner: Steve Duron, Radio Operator: Leon Grabill, Ball turret gunner: Jim Flaherty, Waist gunner: Don Willgus, and Tail gunner: Bill Barton.

The region bears witness to many accidents including a Mosquito from RAF Marham, which suffered structural failure of the wing root with two fatalities.

Little exists about the presence or purpose of Barton Bendish other than a few mentions in the operational record books of these squadrons, or in the recordings of the writings of RAF Marham personnel and some local memories. Rumours and some investigations from official sources (geograph.org.uk) state a ‘huge military (HQ) bunker’ and hard standings, along with possible air raid shelters, but there has been no official recordings made, either photographic or measurements of these, and so their existence cannot be proven one way or another. No other physical buildings (other than the pill boxes) have ever been confirmed as having been built and because the airfield is only listed as a satellite, or landing ground of the parent airfield RAF Marham, it is unlikely they would have existed at all.

Today there are no signs, other than the pill boxes, of the airfield’s location, and so it would seem to be another case of an airfield completely disappearing!

Continuing on from Barton Bendish, toward Norwich we shortly arrive at RAF Marham, one of the RAF’s few remaining front line fighter stations.

RAF Marham

No journey of this nature would be complete without stopping at an active airfield, in this case RAF Marham. An abundant amount of information and photographs exist about Marham and I won’t dwell on it here, but for the enthusiast good photographs can be taken from a number of sites around the airfield, with care and caution. Until 2019 it was home to the RAF’s Tornado squadron, but American built F-35s replaced both them and the Harrier as both the RAF’s and Navies strike capability. The Tornadoes were regularly on active service, operating in the Middle East, their stay of execution delayed by politics, technical problems and an ever-increasing costs of the F-35. In preparation of the F-35’s arrival a whole new area was developed for training purposes and specialist landings pads and runways built to prepare crews for carrier training.

The F-35s finally arrived, and the Tornado was withdrawn from service. A nine ship formation made a farewell tour passing over the station before landing. A further nationwide tour saw a three ship formation fly across a range of sites around the country. A new era had dawned.

Marham Aviation Heritage Centre

Whilst at Marham, take in the delights of the Marham Heritage Centre, located near to the main gate on Burnthouse Drove. The centre is only open on limited days so do check their website before heading off. They hold a lot of information, archives and memorabilia relating to the history of RAF Marham, from its inception in the First Word War through the Second and on into the Cold War and the present day. They also hold a number of ‘open days’ where they invite speakers in, including the one I attended, with Colin Bell DFC an ex Mosquito pilot based at RAF Downham Market during World War 2. The volunteers are all ex Marham and are delightful, helpful people who are very knowledgeable about Marham’s history. I highly recommend it.

Resting not more than a mile or so from the boundary of Britain’s front line fighter base RAF Marham, is an airfield that never made it beyond the First World War. However, its importance cannot be denied nor should it be over looked. Key to aviation in Norfolk and to the Royal Air Force as a whole, it played a major part in both, and therefore is pivotal to today’s modern air force. Opened originally as a satellite by the Royal Naval Air Service, it became not only one of Norfolk’s first, but the biggest First World War, fixed wing aircraft airfield, only four airship stations were bigger. Leading the way for the aviators of today’s Royal Air Force, we look back at the former RAF Narborough.

RAF Narborough

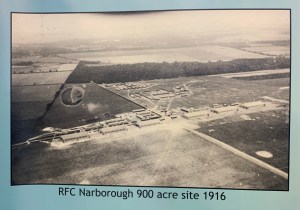

Originally constructed as the largest aircraft base of the First World War, Narborough Airfield in Norfolk has been known by a variety of names over the years: Narborough Aerodrome, RNAS Narborough, RFC Narborough, and later RAF Narborough. However, the most unofficial — and arguably the most evocative — title, ‘The Great Government Aerodrome’, offers a sense not only of its vast scale (spanning over 900 acres), but also of the diversity of aircraft and personnel stationed there. Initially operated by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), the site later came under the control of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), and eventually the newly-formed Royal Air Force (RAF), with each change of name reflecting the evolving structure and ownership of Britain’s early air services.

Records show that the site at Narborough had military links as far back as 1912, in the year that the RFC was established when both the Naval Air Organisation and the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers were combined. Unfortunately, little exists to explain what the site was used for at this time, but it is thought that it was used by the army for training with horses and gun carriages. In later years, it was used as a base from which to counteract the threat from both the German Zeppelin and Schütte-Lanz airships, and also to train future pilots of the RFC and RAF.

Narborough’s history in these early days is therefore sketchy, few specific records exist as to the many changes that were taking place at this time particularly in relation to the development of both the RNAS and the RFC.

However, Narborough’s activities, and its history too, were no doubt influenced on July 1st 1914, when the name RNAS Narborough was officially adopted, and all Naval flying units of the RFC were transferred over to the control of the Navy. A major development in the formation of both forces, there were at this point, a total of: 111 officers, 544 other ranks, seven airships, fifty-five seaplanes (including ship-borne aircraft) and forty aeroplanes in RNAS service.*1 Some of these may well have seen service at Narborough at this point.

Narborough’s first interaction with flying occurred when a solo flyer – thought to have been Lt. F. Hodges in an Avro 504 *2 – touched down on farmland near to Battles’ Farm in the Autumn of 1915. Neither the pilot, the aircraft type nor the purpose of the landing can be substantiated, but it may well have been the precursor to the development of an airfield at this site.

The airfield itself was then developed, opening early that year (1915), on land that lay some 50 feet above sea level. It sat nestled between the towns of Kings Lynn (10 miles), Swaffham (5 miles); and Downham Market (9 miles), and a mile or so away from the small village of Narborough. A smaller aerodrome would, in 1916, open literally across the road from here, and at 80 acres, it would be tiny in comparison. However, over time, it would grow immensely to become what is today’s RAF Marham, an active airfield that has matured into one of the RAF’s top fighter airfields in the UK.

So by mid 1915, Narborough’s future had been decided, designated as a satellite station to RNAS Great Yarmouth, (itself commissioned in 1913) it was initially to be used as a night landing ground for those aircraft involved in attacks on enemy airships, the most likely reason for its location. No crews were permanently stationed here at the time however, ‘on-duty’ crews later being flown in to await the call to arms should an airship raid take place over East Anglia.

This first arrival of an aircraft in August 1915, led to the site being kept in use by the RNAS for the next ten months. During that time, aircraft of the Air Service would patrol the coastline around Norfolk, using aircraft mainly from Great Yarmouth along with a series of emergency landing grounds including Narborough. The threat from German airships at this time being very real. These landing grounds were strategically placed at intervals along the coastline with others more inland, these included: Aldeborough, Burgh Castle; Covehithe; Holt and Sedgeford all of which combined to make North Norfolk one of the densest regions for airfields at that time. But, and even with all these patrols, the roaming airships that made their way across the region had little to worry about as many of the fighter aircraft used could neither reach them at the higher altitudes nor locate them in poorer weather.

However, as a night landing ground, little activity would directly take place at Narborough (there are no recordings of airship sightings from Aircraft using the airfield) and so after a dormant ten months, the RNAS decided it was surplus to requirements and they pulled out leaving Pulham the only ‘in-land’ station larger than Narborough open in Norfolk at that time.

The future of Narborough could have so easily ended there, but even as closure plans were made, its future was still relatively secure, and it would not be long before a new user of the site would be found. Discussions were already in hand for the RFC to take over, provided the land owners’ permitted it! Luckily they did, and soon fifty acres of rough terrain and a small number of canvas flight sheds were theirs. As for staff accommodation, there was none, so when 35 Sqn arrived at the end of May 1916, Bell tents and make shift accommodation had to be erected by the personnel, in order to protect themselves from the harsh Norfolk elements.

With the First World War raging across the fields of Flanders, the demand for aircraft and trained crews grew rapidly. These new flying machines were evolving swiftly into lethal weapons and highly effective reconnaissance platforms, capable of identifying enemy positions and directing artillery fire with increasing accuracy. To meet the urgent need for trained airmen, hurried training programmes were established, and Narborough soon became a vital preparation ground for budding pilots.

Training, by any standard, was rudimentary. Recruits were required to pass a series of written examinations, followed by up to twenty hours of solo flying, a number of cross-country flights, and two successful landings. Added to this was a fifteen-minute flight at 8,000 feet, culminating in a dead-stick landing — that is, returning safely to earth with the engine cut. It was, in truth, barely enough experience for what lay ahead in the violence of aerial combat.

Like many newly established stations, Narborough was designated as an RFC training site — officially known as a Training Depot Station — joining a growing network of such facilities across Norfolk, Suffolk, and Lincolnshire. Their primary role was to prepare pilots for the rigours of air combat, with instruction in dog-fighting, aerobatics, cross-country navigation, and formation flying.

With the arrival of the RFC came immediate expansion. Additional acreage was acquired that same year, extending the airfield westward beyond the area already occupied by the RNAS, bringing it close to the present-day boundary of RAF Marham. As was often the case with wartime construction, adjustments to the local infrastructure were necessary. A road that once bisected the site was eventually closed to accommodate the growing airfield footprint.

So, it was during June 1916 that the first RFC squadron would make use of Narborough as an airfield, 35 Sqn transferring over here from Thetford with Vickers FB.5 and FE.2bs. disposing of their D.H.2s and Henry Farman F.20s in the process. Within two months of their arrival, the nucleus of the squadron would then be used to form a new unit, 59 Sqn, who were also to be stationed here at Narborough (under the initial temporary command of Lieutenant A.C. Horsburgh) with RE8s. On the 16th August, Horsburgh would take on a new role when the new permanent commander Major R. Egerton, was transferred in. It would be he who would take the unit to France the following year and command until his death in December 1917.

During their time here, these daring young trainees, many whom were considered dashing heroes by the awe-inspired locals, would display their skills for all who lined the local roads to see. As these eager young men quickly learned though, flying was not always ‘fun’, and the dangers of the craft were always present, many with dire consequences. Accident rates were high and survival from a crash was rare, even ‘minor’ accidents could prove fatal. All Saints church yard at Narborough, pays testament to their dangerous career with fourteen of the eighteen military graves present being RFC/RAF related.

The initial drive for both these squadrons was to train pilots in the art of cavalry support, using advanced pilot training techniques. This included being able to send Morse code messages at a rate of six words per minute*2 whilst flying the aircraft over enemy territory – certainly no mean feat.

Deaths on and off the airfield were commonplace and not all aviation related either. During late June 1916, one of the Air Mechanics of 59 Sqn, Charles Gardner, suffered a heart attack and died, just one day prior to the official formation of his squadron. Whilst not considered to have been directly related to his role, his loss saw the beginning of a string of deaths in August that would set the scene for the coming months.

The first of these was another thought to be, unrelated aviation death, although whether or not Corporal Patrick Quinn was on duty at the time is unclear. He died on August 18th, whilst riding his motorcycle in the vicinity of the airfield, the narrow Norfolk roads catching him unaware. Then, just two days later on August 20th, the first of many fatal air accidents would occur.