USAAF

RAF Sculthorpe – A relic of the Cold War (Part 3)

RAF Sculthorpe – A relic of the Cold War (Part 2)

RAF Sculthorpe – A relic of the Cold War (Part 1)

M/Sgt. Hewitt Dunn – Flew 104 missions.

RAF Framlingham (Parham) otherwise known as Station 153, achieved a remarkable record, or rather one man in particular did. His name was Hewitt Dunn, a Master Sergeant in the U.S.A.A.F and later the U.S.A.F.

Known as “Buck” he would achieve the remarkable record of completing 104 missions with the 390th Bombardment Group (Heavy) – a record that astounded many as life expectancy in a heavy bomber was short, and few survived beyond one tour of 30 missions.

Hewitt Tomlinson Dunn (s/n 13065206) was born on July 14th 1920. He progressed through school to join the Air Corps where he was assigned to the 390th Bombardment Group (Heavy), 13th Combat Wing, 3rd Air Division, Eighth Air Force, as a gunner in December 1943.

His first mission was with the 569th Bombardment Squadron in the following January. He completed his first gruelling tour of 30 missions by April that year, upon which he immediately applied for a further tour that he would complete by the summer of 1944. His attitude of ‘its not over until its won’, would see him accept a further remarkable third tour, virtually unheard of for a heavy bomber crew member.

On Friday, April 6th 1945, mission 930, an armada of aircraft of the U.S.A.A.F would strike at the marshalling yards in Leipzig, Germany. Inside B-17 #43-38663, ‘The Great McGinty‘, was Hewitt Dunn.

After the mission Dunn described how earlier at the morning briefing, he, like so many of his colleagues, had been a little ‘nervous’. Then, when the curtain was pulled back, their nervousness was justified, Leipzig – the 390th had been there before.

Many crews in that briefing would look to Dunn for signs of anguish, if he remained steady and relaxed, they knew it would be ‘easy’, if he sat forward, then it was going to be a difficult one. The atmosphere must have been tense.

Luckily, unlike other missions into the German heartland, this one turned out to be ‘just another mission’ a ‘milk run’. Much to the huge relief of those in command of the 390th, all aircraft returned safely.

On his arrival back at Framlingham, Dunn was greeted by cheering crowds, ground crews lifted him high in their air carrying him triumphantly away from his aircraft, it was a heroes welcome.

By the time the war had finished, Dunn had flown in 104 missions, he had been a tail gunner on twenty-six missions, twice a top-turret gunner, a waist gunner and the remainder as togglier (Bombardier). He had flown over Berlin nine times, he claimed a FW-190 shot down and had amassed an impressive array of medals for his bravery and actions, and all at just 24 years old.

Post war, he continued to fly as an Instructor Gunner for B-52s in the 328th Bomb Squadron, 93rd Strategic Bomb Wing, at Castle Air Force Base in California. Here he was described as “quiet and reserved” and never talked about his war experiences. He was “handsome man with black hair”, and only when he wore his dress uniform, did others realise how well decorated he was.

Dunn was considered a rock by those who knew him and perhaps immortal, but he was not, and on June 15th , 1961 after flying for a further 64 flights, he was killed. Details of his death are sketchy, but the man who had flown in more missions than any other person in the Eighth Air Force and had gone to train others in that very role, was highly decorated. He was looked up to and liked by those who knew him.

Following his death a service was held in Merced, California, his body was then taken to Arlington National Cemetery in Washington D.C. where he was finally laid to rest in grave number 3675, section 28.

For a man who achieved so much in his fighting career, little exists about him or his achievements. Maybe, by the end of the war, records were no longer needed, tales of dedication and bravery were no longer useful propaganda. Whatever the reason, Hewitt Dunn’s name should be heavily embossed in the history books of the Second World War.

Hewitt Dunn’s medal tally:

– Air Force Longevity Service Award with 3 oak leaf clusters

– Air Medal with 13 oak leaf clusters (2 silver, 3 bronze)

– Air Medal with 7 oak leaf clusters (1 silver, 2 bronze)

– American Campaign Medal

– Distinguished Flying Cross with 1 oak leaf cluster

– Good Conduct Medal

– National Defence Service Medal

– Silver Star

– World War II Victory Medal

– European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 1 bronze star

– European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 1 silver star

Hewitt Dunn’s story is one of many featured in Heroic Tales.

Lt. Col. Leon Vance 489th BG – Medal of Honour.

The story of Leon Vance is one of the saddest stories to emerge from the Second World War. He was a young American, who through his bravery and dedication, saved the lives of his colleagues and prevented their heavily stricken aircraft from crashing into populated areas of southern England. Following a mission over France, his was very severely injured, but miraculously fought on.

The story of Leon Vance is one of the saddest stories to emerge from the Second World War. He was a young American, who through his bravery and dedication, saved the lives of his colleagues and prevented their heavily stricken aircraft from crashing into populated areas of southern England. Following a mission over France, his was very severely injured, but miraculously fought on.

Leon Robert Vance, Jr. known as ‘Bob’ to his family and friends, was born in Enid, Oklahoma, on August 11th, 1916. He graduated from high school in 1933 after receiving many honours and being singled out as a high performing athlete. He went on, after University, to the prestigious Training College at West Point in 1935, staying until his graduation four years later in 1939. It was here, at West Point, he would meet and marry his wife Georgette Brown. He and Georgette would later have a daughter, after whom Vance would name his own aircraft ‘The Sharon D’.

Vance would become an aircrew instructor, and would have various postings around the United States. He became great friends with a Texan, Lieutenant Horace S. Carswell, with whom he would leave the Air Corps training program to fly combat missions in B-24 Liberators. They became great friends but would go on to fight in different theatres.

Prior to receiving his posting, Vance undertook training on Consolidated B-24s. Then, in October 1943, as a Lieutenant Colonel, he was posted to Europe with the newly formed 489th Bombardment Group (Heavy), as the Deputy Group Commander. One of the last groups to be assigned to the European theatre, they formed part of the 95th Combat Bombardment Wing (2nd Bomb Division), Eighth Air Force, and were sent to RAF Halesworth (RAF Holton) designated Station 365 by the USAAF.

The group left their initial base at Wendover Field, Utah in April / May 1944 and their first mission would be that same month on May 30th, 1944, as part of a combined attack on communication sites, rail yards and airfields. A total of 364 B-24s were to attack the Luftwaffe bases at Oldenburg, Rotenburg and Zwischenahn, along with other targets of opportunity far to the north in the German homeland. With only 1 aircraft lost and 38 damaged, it was considered a success and a good start to the 489th’s campaign.

As the build up to Normandy developed, Vance and the 489th would be assigned to bombing targets in northern France in support of the Normandy invasion about to take place further to the south. An area the unit would concentrate on, prior to the Allied beach invasion on June 6th that year.

The day before D-day, the 489th would fly to Wimereaux, in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France. This would be Leon Vance’s final mission.

B-24H Liberator of the 489thBG, RAF Halesworth*2

The group, (Mission 392), consisted of 423 B-17s and 203 B-24s and were to hit German coastal defences including: Le Havre, Caen, Boulogne and Cherbourg areas as a precursor to the Normandy invasion. Some 127 P-47s and 245 P-51s would support the attacks. The 489th would assemble at 22,500 feet on the morning of June 5th, proceed to the south of Wimereaux, fly over dropping their payload, and then return to England. On the run in to the target, Vance was stationed behind the pilot and copilot. The lead plane encountered a problem and bombs failed to jettison. Vance ordered a second run, and it was on this run that his plane, Missouri Sue, took several devastating hits.

Four of the crew members, including the pilot were killed and Vance himself was severely injured. His foot became lodged in the metal work behind the co-pilots seat. There were frantic calls over the intercom and the situation looked bad for those remaining on board. To further exacerbate the problems, one of the 500lb bombs had remained inside the bomb bay armed and in a deadly state, three of the four engines were disabled, and fuel spewed from ruptured lines inside the fuselage.

Losing height rapidly, the co-pilot put the aircraft into a dive to increase airspeed. The radio operator, placed a makeshift tourniquet around Vance’s leg, and the fourth engine was feathered. They would then glide toward the English coast.

The aircraft was too damaged to control safely, so once over English soil, Vance ordered those who could, to bail out. He then turned the aircraft himself out to the English Channel to attempt a belly landing on the water. A dangerous operation in any aircraft, let alone a heavy bomber with an armed bomb and no power.

Still trapped by the remains of his foot, laying on the floor and using only aileron and elevators, he ensured the remaining crew left before the aircraft struck the sea. The impact caused the upper turret to collapse, effectively trapping Vance inside the cockpit. By sheer luck, an explosion occurred that threw Vance out of the sinking wreckage, his foot now severed. He remained in the sea searching for whom he believed to be the radio operator, until picked up by the RAF’s Air Sea Rescue units.

Vance was alive, but severely injured. He would spend a number of weeks, recuperating in hospital, writing home and gradually regaining his strength. Disappointed that his flying career was over, he looked forward to seeing his wife and young child once more. However, on a recuperation trip to London, Vance met a young boy, who innocently, and without thought, told him he wouldn’t miss his foot. The emotional, impact of this comment was devastating to Vance and he fell into depression. Then, news of his father’s death pushed him down even further.

Eventually, on July 26th, 1944 Vance was given the all clear to return home and he joined other wounded troops on-board a C-54, bound for the US. It was never to arrive there.

The aircraft disappeared somewhere between Iceland and Newfoundland. It has never been found nor has the body of Leon Vance or any of the others on board that day. Vance’s recommendations for the Medal of Honour came through in the following January (4th), but at the request of his wife, was delayed until October 11th 1946, so his daughter could be presented the medal in her father’s name.

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty on 5 June 1944, when he led a Heavy Bombardment Group, in an attack against defended enemy coastal positions in the vicinity of Wimereaux, France. Approaching the target, his aircraft was hit repeatedly by antiaircraft fire which seriously crippled the ship, killed the pilot, and wounded several members of the crew, including Lt. Col. Vance, whose right foot was practically severed. In spite of his injury, and with 3 engines lost to the flak, he led his formation over the target, bombing it successfully. After applying a tourniquet to his leg with the aid of the radar operator, Lt. Col. Vance, realizing that the ship was approaching a stall altitude with the 1 remaining engine failing, struggled to a semi-upright position beside the copilot and took over control of the ship. Cutting the power and feathering the last engine he put the aircraft in glide sufficiently steep to maintain his airspeed. Gradually losing altitude, he at last reached the English coast, whereupon he ordered all members of the crew to bail out as he knew they would all safely make land. But he received a message over the interphone system which led him to believe 1 of the crew members was unable to jump due to injuries; so he made the decision to ditch the ship in the channel, thereby giving this man a chance for life. To add further to the danger of ditching the ship in his crippled condition, there was a 500-pound bomb hung up in the bomb bay. Unable to climb into the seat vacated by the copilot, since his foot, hanging on to his leg by a few tendons, had become lodged behind the copilot’s seat, he nevertheless made a successful ditching while lying on the floor using only aileron and elevators for control and the side window of the cockpit for visual reference. On coming to rest in the water the aircraft commenced to sink rapidly with Lt. Col. Vance pinned in the cockpit by the upper turret which had crashed in during the landing. As it was settling beneath the waves an explosion occurred which threw Lt. Col. Vance clear of the wreckage. After clinging to a piece of floating wreckage until he could muster enough strength to inflate his life vest he began searching for the crew member whom he believed to be aboard. Failing to find anyone he began swimming and was found approximately 50 minutes later by an Air-Sea Rescue craft. By his extraordinary flying skill and gallant leadership, despite his grave injury, Lt. Col. Vance led his formation to a successful bombing of the assigned target and returned the crew to a point where they could bail out with safety. His gallant and valorous decision to ditch the aircraft in order to give the crew member he believed to be aboard a chance for life exemplifies the highest traditions of the U.S. Armed Forces”*2

Leon Vance’s actions would be remembered. His local base in Oklahoma was renamed ‘Vance Air Force Base’ on July 9th, 1949. The gate at Tinker Air Force Base, Oklahoma was also later named after him on May 9th, 1997, and his name appears on the ‘Wall of the Missing’ at Madingley American War Cemetery in Cambridge, England.

The American War Cemetery, Madingley. Leon Vance’s Name Appears on the wall of the missing (to the left of the picture).

Leon Robert Vance, Jr. (August 11th, 1916 – July 26th, 1944)

For other personal tales, see the Heroic Tales Page.

Sources.

* Photo public domain via Wikipedia

*1 “Medal of Honor recipients – website World War II”.

*2 Photo Public Domain via Wikipedia.

RAF North Witham – Leading the way into Normandy.

If you follow the A151 towards the main A1, close to the Lincolnshire / Leicestershire border, and you come across Twyford Woods, and an airfield that is little known about, yet its part in history is perhaps one of the most important played by any airfield in Britain. Famous battles such as the Normandy invasion, the Ardennes and the crossing of the Rhine all took place because of the events that occurred here, and were it not for this airfield, many may not have been as successful as they were. In Trail 3, we head further west to perhaps one of Britain’s best kept secrets – RAF North Witham.

RAF North Witham (Station 479)

RAF North Witham sits quietly amongst the trees of Twyford Woods, a site originally known as Witham Wood, which is now a public space owned and maintained by the U.K.’s Forestry Commission.

Originally, North Witham was one of twelve airfields in the Leicestershire cluster intended to be an RAF bomber station for No. 7 Group, however, it was never used operationally by the Royal Air Force, instead like ten others in the area, it was handed over to the US Ninth Air Force and in particular the IX Troop Carrier Command.

As it was originally designed as a bomber station it was built to the Air Ministry’s class ‘A’ specification, formed around the usual three triangular runways, perimeter track and aircraft hardstands. With construction beginning in the mid-war years 1942/43, its main runway would be 2000 yds long, with the second and third runways 1,400 yds in length and all 50 yds wide. To accommodate the aircraft, 50 ‘spectacle’ style dispersals were built, scattered around the adjoining perimeter track. As a bomber base it had a bomb store, located to the north-eastern side of the airfield, with the admin and technical site to the south-east. The usual range of stores and ancillary buildings adorned these areas. One architectural feature of North Witham was its operations block, built to drawing 4891/42, it was larger than most, with ceilings of 14 feet high. Amongst the myriad of rooms were a battery room, cipher office, meteorology room, PBX, traffic office and teleprinter room, all accessed through specially designed air locks. A further feature of this design was the attachment of a Nissen hut to house plant and boiler equipment, a feature not commonly seen at this time.

Aircraft maintenance could be carried out in one of two ‘T2’ hangars with additional work space provided by one of six ‘Butler’ hangars. Designed and built by the Butler Manufacturing Company of Kansas, USA, these were supplied in kit form and had to be erected on site by an Engineer Aviation Battalion. These hangars consisted of rigid box section girders over a canvas cladding, and once fully erected, gave a wide 40 ft span. Quite a rare feature, these types of structures were only built in limited numbers during the Second World War and only appeared on American occupied airfields. Post-war however, they were far more commonly used appearing on many American cold-war sites across the UK.

A ‘Butler’ hangar under construction by members of the 833rd Engineer Aviation Battalion (EAB) at a very snowy North Witham (@IWM479)

The Ninth Air Force was born in 1942 out of the ashes of the V Air Support Command, and then combined with units already located in the England operating under the American Eighth Air Force. Its initial activities focused on the allied push across North Africa followed by the move up into southern Europe through Italy.

Moving to England in October 1943, it then became the tactical Air Force that would support the Normandy invasion, supplying medium bombers, operating as troop support and finally providing supply flights. Facilitation of this massive invasion required both a huge backup, and an intricate supply and support network. North Witham would form part of this support network through both repair and maintenance of the troop carrier aircraft that were operated by the Ninth Air Force – primarily the C-47s. The main group undertaking this role at North Witham was the 1st Tactical Air Depot comprising the 29th and 33rd Air Depot Groups between January and September 1944*1. One of a number of depots, they were once described as the “backbone of Supply for the Army Air Force”, and had a complicated arrangement that encompassed numerous groups across the entire world theatre.

For such a large base, North Witham would be operationally ‘underused’, the only unit to fly from here being those of the IX Troop Carrier Command (TCC), who would primarily use C-47 ‘Skytrains’ – an established and true workhorse, and one that would go on to supply many air forces around the world.

During the Sicily campaign, it was found that many incoming aircraft were not finding the drop zones as accurately as they should, and as a result, paratroops were being widely and thinly scattered. More accurate flying aided by precise target marking was therefore required, and so the first Pathfinder School was set up.

The IX TCC Pathfinder School (incorporating the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Pathfinder Squadrons) was formed whilst the TCC was at RAF Cottesmore in Rutland. Initially having only seven C-47 aircraft, it arrived at North Witham on March 22nd 1944. These aircraft were fitted with, at the time, modern Gee radar and navigation equipment, along with SCR-717 navigational radar housed in a dome beneath the fuselage of the aircraft. This combination of equipment would allow the aircraft to be used as ‘Pathfinders’, and would be used to train both crews and paratroops of the 101st and 82nd Airborne to mark targets prior to the main invasion force arriving.

These crack troops would train at North Witham before returning to their own designated bases to pass on their newly acquired skills. The idea being that these troops would set up ‘homing’ stations using ‘Eureka’ beacons that would connect to ‘Rebecca’ receivers in the aircraft (distinguished from the outside by antenna protruding from the nose). This would allow flying to near pinpoint accuracy even in poor weather or at night; something that would be employed with relative success in the forthcoming Normandy landings.

On arrival at North Witham, the Pathfinders were accommodated in the huts originally provided for the depot’s crews – some 1,250 enlisted men and 75 officers. Many of these displaced men were rehoused in tents along the northern end of the site which only added a further strain to the already rudimentary accommodation that was already in place at the airfield. At its height, North Witham would house upward of 3,700 men in total, a figure that included an RAF detachment of 86 men and large quantities of GIs.

After arrival, the crews began training for the invasion. Flying cross country flights enabled them to practise using their new radar sets, flying in all weathers, at night and during the day. By D-Day, all navigators had been using the equipment in excess of 25 hours and were considered more than competent in its operation.

With postponements of the invasion came frustration, crews and paratroops mentally prepared for war were let down, there was little for them to do to release the tension that many must have felt.

On June 5th, after the plan was finally given the go ahead, some 821 Dakotas at various sites across England were primed ready for the initial wave of the invasion. Timing was of the utmost importance. As rehearsals had shown, seconds could mean the difference between life and death – for the crews of the C-47s, the pressure was on.

Around 200 Pathfinders of North Witham were the first to leave the UK and enter the Normandy arena. Departing late in the evening of June 5th, men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne climbed aboard their twenty C-47s and rose into the night sky. North Witham based C-47A*2 ‘#42-93098’ piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch*3, led the way. Nineteen other North Witham aircraft joined Crouch that night, and remarkably only one aircraft was lost in the entire flight. Flying under mission ‘Albany‘, the Douglas built C-47A-15-DK Skytrain, #42-92845 (aircraft #4) was lost en route either due to mechanical failure, or as some sources say, following a direct hit by Anti-Aircraft fire. Either way, the aircraft lost an engine and was forced to ditch in the sea. Once down, the crew and paratroops on-board were rescued by the British destroyer HMS Tartar.

The Crew of C-47A #42-93098, a few hours before they left for Normandy. Including Pilot, Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch (centre), Captain Vito Pedone (copilot), Captain William Culp (Navigator), Harold Coonrod (Radio Operator), along with Dr. Ed Cannon (physician), and E. Larendeal (crew chief)*1

The aircraft flew in groups of three in an in-line ‘V’ formation; aircraft 1, 2, 3 followed by 4, 5, 6; 19 and 20 (added as a late decision); 7, 8, 9; 10, 11, 12; then 16, 17 and 18. The formation was finally completed with aircraft 13, 14 and 15 bringing up the rear. Each C-47 would deposit its collection of Paratroops over six drop zones (DZ) A, C, D, O, N and T between 00:20 and 02:02.

Flying alongside aircraft #19, the only pair on the flight, was C-47 #20 piloted by 1st Lt. Paul F. G. Egan, of Massachusetts. Joining him in the aircraft were: Sgt. Jack Buchannon, Crew Chief (Mass); 2nd Lt. Richard A. Young, Co-Pilot (Ohio); 2nd Lt. Fern D. Murphy, Navigator (PA); Staff Sgt. Marvin Rosenblatt, Radio Operator (NY) along with ten Combat Engineers of the 101st Airborne who were dropped at Sainte-Mère-Église on the Cherbourg Peninsula early in the morning 6 June 1944.

Lt. Paul Egan had a remarkable service history, serving in each of the US Army, US Army Air Force and US Air Force after the war, a service that stretched from 1939 to 1967. His remarkable record includes: Pearl Harbour in 1939 and the Japanese attack in December 1941, the Battle of Midway in 1942, followed by advanced training in 1943. This training kept Lt. Egan in military intelligence as a Pathfinder pilot flying mostly C-47s out of both North Witham and later Chalgrove. As well as dropping the paratroopers on D-Day in Operation Market Garden, he also dropped troops in Operation Varsity along with every other major airborne operation flown from England. He also flew bombing missions in B-17s and flew ‘secret’ missions in early 1945. At the signing of the Japanese surrender onboard the USS Missouri on September 2nd 1945, he was the only USAAF representative there, General McArthur wanting someone who was present at Pearl Harbour to also be present at the surrender. His record is certainly remarkable and one to admire.*5

Photo taken at North Witham Air Base, England on June 5, 1944, the night before D-Day. C-47 #20 (note the number chalked in front of the door to ensure paratroops boarded the right aircraft, and the crudely painted invasion stripes) one of the first 20 aircraft to fly with the elite group, the Pathfinders. Front row: Sgt. Jack Buchannon, Crew Chief; 2nd Lt. Richard A Young, Co-Pilot; 2nd Lt. Fern D. Murphy, Navigator; 1st Lt. Paul F. G. Egan, Pilot (Captain); Staff Sgt. Marvin Rosenblatt, Radio Operator along with ten 101st Airborne Combat Engineers dropped on the Cherbourg Peninsula early morning 6 June 1944, “D-Day” (Photo courtesy Jean Egan).

Pathfinder training continued at North Witham beyond D-Day, well into 1944. The scope of those trained expanding to include Polish paratroops of the 1st Independent Polish Airborne Brigade, who would perform a similar role to their American counterparts. These various Pathfinder groups would go on to have long and distinguished careers, supporting the battles at Arnhem, the Ardennes and also Operation Varsity – the Allied crossing of the Rhine.

As the Allies pushed further into enemy territory, the flying distance from England became too great and so new airfields were either hastily constructed on the continent or captured airfields refurbished. As a result, the Pathfinder School soon moved away to Hampshire and the maintenance units, needed nearer the front lines, gradually departed to these newly acquired bases on the continent.

September 1944 would see big changes in the Ninth and the knock-on was felt at North Witham. Firstly, the IX TCC transferred from the Ninth AF to the First Allied Airborne Army, and as a result, the Air Depot title was changed to IX Troop Carrier Service Wing (Provisional), which was re-assigned to aid and supply the new Troop Carrier Groups (TCG) now based in France. To accomplish this new role, groups often used borrowed or war-weary C-47s, C-46 (Commandos) or C-109s (converted B-24 Liberators) to fulfil their role. Secondly, the Pathfinder School was re-designated IX Troop Carrier Pathfinder Group (Provisional) and they moved away from North Witham to their new base at Chalgrove near Oxford. Now much quieter, life otherwise continued on at North Witham, but it wouldn’t long before the demand for UK-based maintenance and repair work would slow, and within months North Witham’s fate would be finally sealed.

As the end of the war approached, the airfield quickly became obsolete, and the long wind-down to closure, that many of these unique places suffered, began to take effect.

By the time the war was over, the last American personnel had pulled out and the site was handed back to the RAF’s 40 Group who, after using it for a brief spell as a maintenance depot themselves, placed it under care and maintenance. It was used as a munitions and hardware store until 1948, and then finally, in 1956, it was closed by the Ministry and within two years the site was sold off.

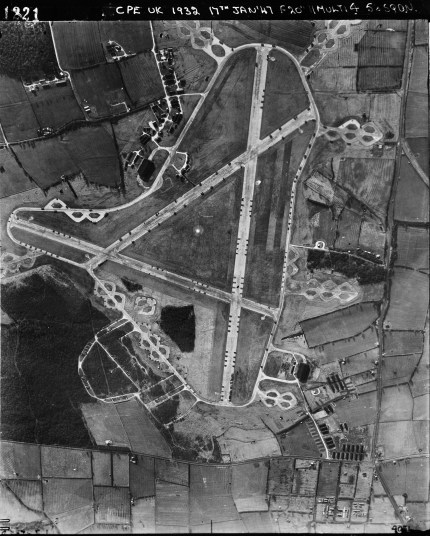

Photograph of North Witham taken on 17th January 1947. The technical site and barrack sites are at the top left, the bomb dump is bottom left. (IWM RAF_CPE_UK_1932_FP_1221)

The site, intact as it was, was returned to the Forestry Commission who planted a range of new tress around the site, covering the vast areas of grass. The technical area was developed into a small industrial unit and perhaps most sadly the watch office left to decay and fall apart.

Today the three runways and perimeter track still exist almost in their entirety, and remarkably, in generally good condition. Largely overgrown with weeds and small trees, the remainder is well hidden obscuring what little there is in the way of buildings – most being demolished and the remains left piled up where they stood. However, a T2 hangar is now used on the industrial estate and the watch office still stands tucked away amongst the trees and undergrowth. This area is a favourite place for dog walkers, and because of its runways, it is accessible for prams and pushchairs. Whilst here, I spoke to quite a few people, remarkably none of them knew of the site’s historical significance let alone the office’s existence!

Today the watch office remains open to the elements. Surrounded by used tyres and in constant threat of the impending industrial complex over the fence, its future is uncertain. Access stairs have been removed, but an entrance has been made by piling tyres up to the door – presumably by those wishing to enter and ‘explore’ further. Little evidence of its history can be seen from the outside, even the rendering has been removed, and so, any possible personal links with the past are more than likely now gone.

Returning back to the main public entrance along the perimeter track, a number of dispersal pens can be found; overgrown but relatively intact, they are a further sign that even here, war was never very far away.

North Witham was one of those ‘backroom boys’ whose contribution, whilst extremely important, is little known about. The work carried out here not only helped to maintain a strong and reliable fighting force, but one that spearheaded the frontal invasion of Normandy. It served as a cold and perhaps uncomfortable home to many brave troops, many of whom took the fight direct to Nazi Germany.

Standing here today, it is quiet and strangely surreal – you can almost hear the roar of engines. Looking along its enormous runways you get an eerie feeling – how many troops also stood here, spending their last few hours in this quiet place. Looking around now, it is difficult to imagine the immense work that went on here, the gathering of equipment as preparations were made for the big push into Normandy on that famous June night.

North Witham is truly a remarkable place, hidden away amongst the trees as a giant time capsule, a monument to those who lived, worked and died during that turbulent time in 1944-45.

Sadly in May 2015, Twyford Woods was the scene of a large illegal rave, over 1000 people attended the event where a number of arrests were made in the violent altercations that took place*4. A sad day that would turn the souls of those who sacrificed themselves for the freedom we take for granted so very easily today.

(North Witham was originally visited in early 2013)

Links and sources (RAF North Witham)

*1 American Air Museum in Britain

*2 C-47A #42-93098 itself was later lost whilst flying with the 439th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) on September 18th 1944, whilst flying in support of Operation ‘Market Garden‘ in Holland.

*3 Superb footage of Crouch and his crew as they depart from North Witham is available on-line, it also shows the Watch Tower in its former glory.

*4 A report of the event is available on the BBC News website.

*5 My sincere thanks go to Jean Egan, daughter of Lt. Paul Egan, for the information and photograph.

An excellent website contain photos of paratroops and air crew as they prepare for embarkation and advance through France.

B-17 Pilot 1st Lt.D. J. Gott and 2nd. Lt W. E. Metzger

War makes men do terrible things to their fellow mankind. But through all the horror and sometimes insurmountable odds, courage and bravery shine through. Two gallant young men both in the same B-17 were awarded the Medal of Honour for acts of extreme bravery in the face of certain death.

Born on 3 June 1923, Arnett. Oklahoma, Donald Joseph Gott, began his air force career at the local base in 1943. By the end of the first year he had achieved the rank of First Lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps. Posted with the 729th. Bomber Squadron, 452nd Bombardment Group to Deopham Green, Norfolk, England, he was to fly a B-17 (42-97904) ‘Lady Jeannette’ along with his crew and co-pilot William E. Metzger.

Metzger was born February 9, 1922 – Lima, Ohio and by the time he was 22 he was a 2nd Lieutenant. He was to meet Gott at Deopham Green, Norfolk and together they would fly a number of missions over occupied Europe bombing strategic targets.

On the 9th November 1944, they took off with their crew on a mission that would take them into the German heartland to bomb the marshalling yards at Saarbrucken.

On this run, the aircraft, was badly hit by flak, three of the engines caught fire and were inoperable, the fires were so fierce that they were reaching the tail of the stricken aircraft.

Further fires within the fuselage started when flares were ignited, and this rapidly caught a hold. Hydraulic lines were severed and the liquid from within was jettisoned onto the burning fuselage. With communication lines cut and unable to contact the crew, both Gott and Metzger had some difficult decisions to make. They had not yet reached the target, the aircraft still held its bomb load and they were deep into occupied territory.

The crew too had suffered badly at the hands of the anti-aircraft fire. The engineer was wounded in the leg and the radio operators arm was severed below the elbow causing great pain and loss of blood. He would die very quickly if medical help was not found. Despite the quick thinking and application of tourniquet by fellow crew members, he soon passed out and fell unconscious.

Gott and Metzger decided that jettisoning the injured radio operator would not result in his receiving medical help and so they would drop the bombs and head for the nearest friendly territory where they could crash-land. Doing this, would risk not only the life of the operator, but that of the crew and themselves should the stricken aircraft explode.

Over the target, they released their bombs and flew alone toward allied territory. Flying low over the village of Hattonville, the aircraft was seen to swerve avoiding a church and homes. At this point, Metzger personally crawled through the aircraft and instructed the crew to bail out. Three chutes were seen by local people, two fell to earth and the third became entangled on the stabiliser and was trapped. A further three were seen moments later, all these escaped. Metzger decided to remain with Gott and try to land the aircraft with the radio operator on board. With only one working engine, Gott and Metzger brought the aircraft down through a series of tight turns and at only 100 feet from safety the aircraft banked and exploded. Crashing to earth it again suffered a second explosion and disintegrated killing all three crew members on board and the crew member still attached to the tail.

1st Lieutenant Gott and his co-pilot 2nd Lieutenant Metzger had shown great courage and determination to complete their mission, and to save their crew from certain death. They had shown the greatest of valour in what was to be the final act of their short lives.

Both men were killed on that day, November 4th 1944 aged 21 and 22 respectively. They were both posthumously awarded the Medal of Honour on the 16th May 1945.

Gott’s remains were returned to the United States and he was buried at the Harmon Cemetery, in Harmon, Ellis County, Oklahoma, USA. Metzger, was returned to his home town and was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery, Lima, Ohio.

Along with Gott and Metzger, crew members who did not survive were: T/Sgt Robert A, Dunlap and S/Sgt T.G. Herman B, Krimminger. The survivors were picked up by a a local field hospital and treated for their injuries: 2nd lt John A, Harland ; 2nd lt Joseph F, Harms ; S/Sgt B.T. James O, Fross ; S/Sgt R.W. William R, Robbins and T/Sg T.T. Russell W Gustafson.

A memorial now stands close to the site of the crash site.

RAF Bircham Newton (Part 5 – The war comes to an end)

After Bircham entered the war in Part 4, and new innovative designs helped to save lives at sea, Bircham continues on and heads towards the war’s end. Numerous squadrons have now passed through this Norfolk airfield, and many more will come. Once the war is over, Bircham enters the wind down, its future uncertain, but on the horizon a saviour is coming and Bircham may well be saved by an unusual guardian.

By 1942, designs in ASR equipment had moved on, and a jettisonable lifeboat had by now been designed. The Hudsons at Bircham were the first unit to have the necessary modifications made to them to enable them to carry such boats, and as a result several crews were saved by the aircraft of 279 Sqn. Many searches however, were not fruitful and lives continued to be lost as a result of the lack of suitable equipment and poor weather.

After ditching B-17 #42-29981 (92nd BG) on 26 July 1943 in the relative safety of a calm sea, the crew managed to escape a and (with difficulty) climb aboard their life raft. An ASR aircraft from RAF Bircham Newton located them and a rescue ensued (AAM UPL 39104).

Moments later, an airborne lifeboat is parachuted down by a Hudson of No. 279 Squadron to the crew. (© IWM C 3691)

During the year yet more front line squadrons would arrive here at Bircham. The first, 502 Sqn brought with it a change of aircraft type, with the Whitley V. The Whitley was a 1930’s design, constructed to Specification B.3/34, and was only one of three front line bombers in service at the outbreak of the war.

Within a matter of weeks, one of these Whitleys, returned from a maritime night patrol, overshot the flare path and crash landed. This particular mark of Whitley was soon replaced by the VII, and as 502 received their new models, so they began their departure to St.Eval; they had only been here at Bircham for a mere month.

March and April 1942 would then see two more units, both operating Hudsons. The first, 407 Sqn, was the first Canadian unit to be based here at Bircham, and would only stay here until October. As part of 16 Group, it would perform attacks on enemy shipping between Heligoland and the Bay of Biscay. The second squadron, 320 Sqn, would arrive at Bircham a month later on April 21st and would remain here for the next year. An entirely Dutch manned unit they had transferred from Leuchars in Scotland where they had been carrying out maritime patrols. The main part of April for 320 Sqn would consist of ferry flights, tests and cross country flying.

The final squadron, 521 (Meteorological) Sqn, was formed here on 22nd July 1942 through the joining of 1401 and 1403 (Met) Flights. These were operating a number of aircraft including the Blenheim IV, Gladiator II, Spitfire V, Mosquito IV and Hudson IIIA, and all passed over to 521 Sqn in the July on its formation. In the following year, March 1943, the squadron would be split again, returning back to two flights once more, Nos 1401 and 1409, thus ending this period of its history. The role of 521 sqn was meteorological, the Gladiators flying locally usually above base, whilst the remainder flew long range sorties over northern Germany or to altitudes the Gladiator could not reach.

There was little ‘front line’ movement in or out of Bircham during 1943, only two new squadrons would be seen here, 695 Sqn with various types of aircraft, and 415 (Torpedo Bomber) Sqn another Canadian unit.

415 were initially a torpedo squadron operating in the North Sea and English Channel areas attacking shipping along the Dutch coast. They arrived here at Bircham Newton in November with both Albacores and Wellingtons, and remained here in this role until July 1944 when they left for East Moor and Bomber Command. During D-day the squadron lay down a smoke screen for the allied advance, taking on the Halifax to join in Bomber Command operations. Throughout their stay they retained detachments at a number of airfields including: Docking and North Coates (Wellingtons) and Manston, Thorney Island and Winkleigh (Albacores). They were well and truly spread out!

695 Sqn were formed here out of 1611, 1612 and 1626 Flights, and performed anti-aircraft co-operation duties using numerous aircraft including: Lysanders, Henleys, Martinets, Hurricanes and Spitfires. They remained here until August 1945 whereupon they departed to Horsham St. Faith now Norwich airport.

The only RAF squadron to appear here at Bircham Newton in 1944, was 524 Sqn. It was originally formed at Oban on the Scottish West coast with the failed Martinet, in October 1943, the squadron lasted a mere two months before being disbanded in the early days of December.

Like a phoenix though, it would be reborn later in April 1944 at Davidstow Moor. By the time it reached Bircham in the July, it was operating the Wellington XIII. After moving to nearby RAF Langham in October, it would eventually disband for the final time in 1945.

It was also during this year that further FAA units would make their presence here at Bircham. 855 Sqn FAA brought along the Avenger, whilst 819 Sqn FAA brought more Albacores and Swordfish. Both these units served as torpedo spotter reconnaissance and torpedo-bomber reconnaissance squadrons.

As the war drew to a close, 1945 would see the winding down of operations and squadrons. Two units would see their days end at Bircham, 598 Sqn with various types of aircraft and 119 Sqn with the Fairey Swordfish, would both be disbanded – in April and May respectfully.

Bircham’s activity then began to dwindle, and its role as a major airfield lessened. From anti-shipping activities to Fighter Command, Flying Training, Transport Command and finally to a Technical Training unit, Bircham was now training the Officers of the future. Flying activity naturally reduced, and small trainers such as the Chipmunk became the order of the day. Whilst a number of recruits passed through here, the most notable was perhaps HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, who made several landings here as part of his flying training in the early 1950s.

Like all RAF Stations, Bircham was the proud owner of several ‘gate guardians’, notably at this time was Spitfire LF Mk.Vb Spitfire ‘EP120’ from around 1955 to late 1962, along with Vampire F MK.3 ‘VF272’.

Spitfire EP120, was a Castle Bromwich model, which entered RAF service in May 1942, with 45 Maintenance Unit (MU) at Kinloss in Scotland. Whilst serving with several squadrons she achieved seven confirmed ‘kills’ before being relegated to a ground instructional air frame. There then followed a period of ‘Gate Guardianship’ standing at the front of several stations including Bircham Newton. In 1967 she was used as a static example in the famous Battle of Britain movie, before being transferred back to gate guard duties. In 1989 she was then transferred to a storage facility at St. Athan along with several other Spitfires awaiting their fate. Finally she was bought by the ‘Fighter Collection‘ in 1993. After a two year restoration, EP120 finally returned to the skies once more, in September 1995 where she has performed displays around the country ever since.

Unfortunately, Vampire VF272 wasn’t so lucky. Whilst her fate is unknown at this time, it is believed she was scrapped on site when Bircham finally closed in 1962.

But it was not to be the end of the story though. In 1965, with the development of the Kestrel, Hawker Siddeley’s VTOL baby, Bircham came to life once more, albeit briefly, with the sound of the jet engine. With tests of the new aircraft being carried out, Bircham Newton once again hung on by its finger nails – if only temporarily.

A year later, Bircham was sold to the National Construction College and the pathways were adorned with young building apprentices, diggers and cranes of varying sizes. Being a busy building college, many of the original buildings have been restored but the runways, flying areas and sadly the watch office, removed. Whilst private, the airfield retains that particular feel associated with a wartime airfield.

Luckily, the main road passes through the centre of Bircham. A project to turn the Station Commanders Office into a heritage centre*9 has come to fruition, using the ground floor space to exhibit photographs, letters, documents and memorabilia from Bircham Newton. A memorial has also been erected and stands outside the centre, just off the main road and is well sign posted. The original accommodation blocks, technical buildings and supporting blocks are still visible even from the road. The 1923 guard-house, is now a shop and the operations block, the reception centre.

Reputedly haunted, the squash courts (built-in 1918) continue to serve their original purpose, and most significantly, the three large C-type hangers and two Bellman sheds are still there – again all visible from the public highway.

RAF Bircham Newton, stands as a well-preserved model one of Britain’s wartime airfields. Although private now, the buildings reflect the once bustling activities of this busy centre of aviation.

In February 2020, the CITB announced that they had sold the site to the Bury St Edmunds based West Suffolk College. The move, it says, was planned as a cost cutting exercise with the loss of some 800 jobs. The intention of the West Suffolk College is to continue with the construction training at Bircham, hopefully preserving the site for generations to come. Only time will tell.

Sources and links for further reading (RAF Bircham Newton):

The full text can be seen in Trail 20 – North Norfolk Part 1.

*1 A detailed history of the production of the HP.15 /1500 can be found on Tony Wilkin’s blog ‘Defence of the Realm‘.

*2 Letter from C.C. Darley (the brother of C.H. Darley) to Sqn Ldr. J. Wake 1st March 1937 (AIR 27/1089/1 Appendix B)

*3 Gunn, P.B. “Flying Lives with a Norfolk theme“, 2010 Published by Peter Gunn.

*4 Pitchfork, G, “Shot down and in the Drink” 2007, Published by The National Archives. – A very interesting and useful book about the development of the ASR service along with true stories of airmen who had crashed in the sea.

*5 BAE Systems website accessed 6/7/21

*6 Traces of World War 2 Website, accessed 11/7/21

*7 Aviation Safety Network website, accessed 21/7/21

*8 Braithwaite, D., “Target for Tonight“, Pen and Sword, 2005

*9 The Heritage Centre is a free to visit site located in the former Station Commanders House. It is only open on set days each year and is fully staffed by volunteers. The project has over the years been updated and reorganised, and is an excellent exhibit of letters, photographs, memorabilia and documents pertaining to the history of Bircham Newton along with material relating to both Docking and Sedgeford. The staff are extremely knowledgeable and more than willing to she this knowledge with you. Opening times and further details can be found on their Facebook page. I visited on October 15th 2023 and would like to thank Jamie and the staff for sharing their knowledge and showing me round the exhibits. I can’t recommend it enough.

National Archives: AIR 27/263/1; AIR 27/788/1; AIR 27/1233/1; AIR 27/1221/1; AIR 27/1222/11, AIR 27/1222/12

Details of 206 Sqn fatalities are available on the 206 Sqn Coastal Command website.

Details of Great Bircham war cemetery graves are available at the role of honour of St Mary’s Church.

September 8th 1943 – Tragedy at RAF Mepal.

On the night of September 8/9th 1943, a force of 257 aircraft comprising 119 Wellingtons, 112 Stirlings, 16 Mosquitoes and 10 Halifaxes took off from various bases around the U.K. to bomb the Nazi gun positions at Boulogne. Included in this force were aircraft from the RAF’s Operational Training Units, and for the first time of the war, five B-17s flown by US aircrews of the USAAF’s 422nd BS, 305th BG at Grafton Underwood. This was the first of eight such missions to test the feasibility of the USAAF carrying out night operations over Europe. After the remaining seven missions, in which the squadron had dropped 68 tons of bombs, the idea was scrapped, the concept considered ‘uneconomical’ although the aircraft themselves proved to be more than capable of the operations.

The Gun battery targeted, was the emplacement that housed the Germans’ long-range guns, and the target wold be marked by Oboe Mosquitoes. With good weather and clear visibility, navigation was excellent, allowing the main force to successfully drop their bombs in the target area causing several huge explosions. However, not many fires were seen burning and the mission was not recorded as a success. Reports subsequently showed that the emplacement was undamaged due to both inaccurate marking by Pathfinders, and bombing by the main force. However, as both anti-aircraft fire and night fighter activity were light, no aircraft were lost during the flight making it a rather an uneventful night.

However, the mission was not all plain sailing, and whilst all crews returned, the night was marred by some very tragic events.

Three Stirlings were to take off from their various bases that night: at 21:00 hrs from Chedburgh, Stirling MK. III, EF136, piloted by F/S. R. Bunce of 620 Sqn; at 21:30, another Stirling MK.III, from 75 Sqn at RAF Mepal, BK809 ‘JN-T*1‘ piloted by F/O I.R.Menzies of the RNZAF; and lastly at 21:58 also from Chedburgh, Stirling MK. I, R9288 ‘BU-Q’ piloted by N.J. Tutt of 214 Sqn. Unfortunately all three aircraft were to suffer the same and uncanny fate, swinging violently on take off. The first EF136 crashed almost immediately, the second BK809 struck a fuel bowser, and the third R9288 ended up in the bomb dump. Miraculously in both the Chedburgh incidents there were no casualties at all, all fourteen crew men surviving what must have been one of their luckiest escapes of the war! The same cannot be said for the second though.

Stirling BK809 was part of a seventeen strong force of 75 Sqn aircraft. Each aircraft was carrying its full load made up of 1,000lb and 500lb bombs. As the Stirling was running along the runway, it swung violently, striking a fuel bowser which sent it careering into houses bordering the edge of the airfield.

One of the occupants of one of the houses, Mr. P. Smith, saw the aircraft approaching and ran into the street to warn others to get clear. As the aircraft struck the rear of the houses, it burst into flames causing some of the bombs to detonate. This brought considerable rubble down on the occupants of the second house, Mr and Mrs John Randall.

Mrs Randall managed to get out, her legs injured, whereupon she was met by a local fireman, Mr. A.E. Kirby of the National Fire Service. Mr. Kirby went on to help search in the wreckage of the house until his attempts were thwarted by another explosion. His body, along with that of Mr. Randall, was found the next day.

Two other people were also killed that night trying to provide assistance, those being F/Sgt Peter Gerald Dobson, RNZAF and Section Officer Joan Marjorie Easton WAAF. F/Sgt. Dobson was later mentioned in despatches. Three members of the crew lost their lives as a result of the accident, F/O. Menzies and F/O. N. Gale both died in the actual crash whilst Sgt. A. Mellor died later from injuries sustained in the accident.

A number of others were injured in the crash and one further member of the squadron, Cpl Terence Henry King B.E.M, was awarded the British Empire Medal “for his bravery that night in giving assistance“.

The mission on the night of September 8/9th 1943 will not go down as one of the most remarkable, even though it was unique in many respects, but it will be remembered for the sad loss of crews, serving officers and civilians alike in what was a very tragic and sad event.

The crew of Stirling BK809 were:

F/O. Ian Robert Menzies RNZAF NZ415002. (Pilot).

P/O. Derek Albert Arthur Cordery RAFVR 136360. (Nav).

P/O. Norman Hathway Gale RAFVR 849986. (B/A).

Sgt. Ralph Herbert Barker RNZAF NZ417189. (W/O).

Sgt. Albert Leslie Mellor RAFVR 943914. (Flt. Eng).

Sgt. Bullivant G RAFVR 1395379. (Upp. G)

Sgt. Stewart Donald Muir RNZAF NZ416967. (R/G).

RAF Mepal was visited in Trail 11.

Sources and Further Reading.

*1 Chorley, 1996 “Bomber Command Losses 1943” notes this aircraft as AA-T.

National Archives: AIR 27/646/42: 75 Sqn ORB September 1943

Chorley, W.R., “Bomber Command Losses – 1943“, Midland Counties, (1996)

Middlebrook M., & Everitt C., “The Bomber Command War Diaries” Midland Publishing, (1996)

Further details of this accident, the crews and those involved can be found on the 75 (NZ) Sqn blog. This includes the gravestones of those killed and a newspaper report of the event.

My thanks also go to Neil Bright for the initial information.