On the eastern coast of Fife in Scotland, lies a remarkable airfield that has to be one of the most extraordinary Second World War airfields in the country. It is a change from the usual sites we look at, being neither RAF nor USAAF, but instead it is a Royal Naval Air Station.

Not only is this site remote, sitting just outside the small village of Crail, and accessible by one road, but it is an airfield that has been locked in a time capsule, an airfield that looks like the Mary Celeste of wartime sites.

As we head north again, this time close to the famous golf course at St. Andrews on the east coast of Scotland, Trail 53 visits the former Royal Naval Air Station (RNAS) at Crail, an airfield that looks like it was left the very day the last man walked out the door.

RNAS Crail (HMS Jackdaw)

Crail has to be virtually unique, complete almost in its entirety, from accommodation, to the technical buildings, its runways and even the Naval watch office, they are all standing (albeit in a poor state) as they were when the site was closed in 1958.

Now very much rundown, it has to be one of the most compete examples of wartime airfields in the UK today. This is primarily due to Historic Scotland who have scheduled the entire site listing many of the buildings for preservation.

Originally Crail was the site of a World War I airfield, opened and closed within a year 1918 -1919, and was designed specifically to train new pilots before posting to front line squadrons in France. The airfield was home to both No. 50 and 64 Training Squadrons, who were both immediately disbanded, and then reformed under the control of the newly formed Royal Air Force as No. 27 Training Depot Squadron RAF, on July 15th 1918.

Flying RE8, FE2b, Avro 504A & 504K aircraft and Sopwith Camels, they were to give airmen who had passed their basic flying training programme, instruction in techniques in both fighter-reconnaissance and air combat. Pilots would progress from one aircraft type to another learning to fly amongst other things, simulated dogfights which hopefully prepared them for combat over northern France.

At the end of 1918 US airmen were being sent across the Atlantic and some of these too were trained here at Crail. But as the war finally closed, there was little need to train new pilots and so flying duties were slowly withdrawn. The number of flights at Crail began to dwindle and its end looked near.

In March of 1919, a cadre of 104 Sqn DH.10s landed here, but with little or no flying taking place, they were soon surplus to requirements, the RAF being cut back to save money. As a result of these cuts, they were no longer needed and so were disbanded at the end of June.

During its short eight month life Crail would be a busy station seeing many aircraft types. It would also be developed quite extensively, having a range of buildings erected on site which included three coupled General Service sheds, recognisable by their curved roof using the ‘Belfast Truss’ construction method; and a single Aircraft Repair Shed, all typical of Training stations in the latter stages of the war.

Like many World War II airfields later on, Crail was unfinished when these first bi-plane units moved in, and once the war was over, like the aircraft, the buildings were all removed and the land returned to agriculture once more.

When war broke out for the second time, Crail was identified as a possible site for a new airfield for use by the Royal Navy (RN), a satellite being used at nearby Dunino. Having a record of good weather and drainage, it was a perfect location, quiet, secluded and on the coast of Scotland. It was an ideal location both for training and for operations over the North Sea.

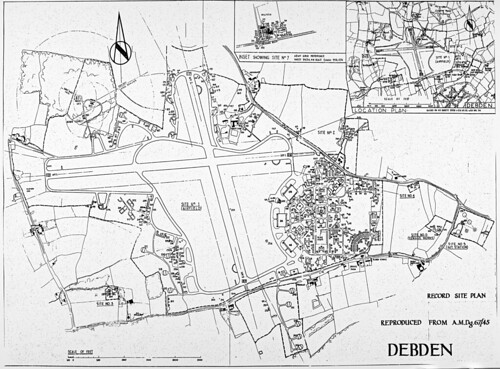

Being a Royal Naval airfield it would differ from RAF airfields in that it had four runways and not three, each being of tarmac. However, because they would not be used for heavy aircraft especially the larger bombers, these runways would be considerably smaller, 3 x 1000 yds and 1 x 1,200 yds each only 33 yds wide. The other reason for these narrow and short runways were that they were used to train pilots to land as they would on aircraft carriers, using much shorter and narrower landings spaces than their RAF counterparts.

World War II Crail would be considerably larger than its First World War predecessor, and would have numerous state-of-the-art buildings and features. With construction starting in 1939, it would open in the Autumn of 1940 but would continue to be adapted and updated right the way through to the war’s end in 1945. As Crail was a Royal Navy station, it would have to follow Royal Navy law and have its crew named after an actual floating vessel. Hence, on October 1st 1940, it was commissioned as HMS Jackdaw, following the tradition of using bird names for land based stations.

As with many wartime RAF airfields, Crail was split by the main road, the accommodation areas to the north-west and the active airfield to the south-east. Accommodation would cater for around 2,000 personnel of mixed rank and gender, WRNs (Wrens) being used, like WAAFs, not only in the administration and communication roles, but for aircraft maintenance, parachute packing and other maintenance duties.

Wren parachute packers at Royal Naval Air Station Crail. © IWM (A 6289)

Many of these accommodation blocks were single story, laid out in blocks of four (some grouped as eight) in a grid-style layout. Whilst separate from the active side of the airfield, it was not truly dispersed as RAF airfields were later on. Also on this site, close to the entrance, are the communal buildings such as the gymnasium/cinema and chapel, providing comfort and entertainment for those off duty times.

On the technical side of the airfield Crail had a number of hangars, an Aircraft Repair Shop, torpedo attack training building (TAT), bombing training building and a watch office along with many other support and technical buildings. A bomb store was located in the southern area of the airfield.

The TAT building revolutionised torpedo attacks, removing the ‘educated’ guesswork that pilots had to make using bow waves, ships’ angles and speed estimations. These deflected attacks reminiscent of deflected shooting by fighter pilots and gunners of the RAF, they were much harder to calculate and so more difficult to score hits. This new ‘F’ director system fed information from the aircraft directly into the torpedo which once released, could accelerate away at accurately calculated deflection angles from the aircraft. These buildings used a large hemispherical screen linked to a TAT trainer which looked not unlike a Link trainer. Designed to drawing number 1697/42 they were large buildings, with a large lighting gantry suspended from the ceiling constructed by technicians from closed theatres in London. The example at Crail was the first such building and led the way to other similar structures being built at other Naval Air Stations. Today this is the only known example left and whilst the innards of the building have gone, it has been listed as a Historic building Category ‘A’ by Historic Scotland.

In conjunction with the synthetic training provided at Crail, cameras were used that would be strapped beneath the wings of the aircraft and would take a photo as the torpedo release button was depressed. Classed as ‘Aerial Light Torpedo’ it was a simulated attack that would take an image of the vessel under attack, allowing an examiner to calculate the success of it without the need to use a dummy torpedo. Pilots at Crail would carry out several mock attacks every day and so the use of a camera and synthetic training, reduced the use of dummy torpedoes that could not be collected once dropped.

A camera attached to the wing of Swordfish at Crail allowed examiners to calculate the success of hits against surface targets.(© IWM A 9413)

An additional aspect of synthetic training at Crail was the bombing teacher building, another rare and rather unique example. An example based on the earliest 1926/1927 designs, it remained unchanged and is said to be the only existing example of its kind left in Britain. The fore-runner of the AML bombing teacher, it was a two-story building that projected an image on to the floor beneath the bomb aimer. Designed to simulate a variety of conditions, the bomb aimer would lay on a platform feeding signals to a projector above, and the image would move simulating an aircraft flying at 90 mph at an altitude of 8,000ft.

But by far the most prominent building at Crail is the Aircraft Repair Shed (ARS) at 250 feet in length with its ‘zig-zag’ roof, these were unique to Naval Air Stations and were able to take numerous aircraft for full strip down and rebuilding work. In conjunction with this were a number of well equipped workshops and seven squadron hangars all 185 feet long and 105 feet wide. Five of these hangars were grouped together in the technical area with two more to the eastern side of the airfield. Specifically designed for naval use, these Pentad transportable hangars were able to accommodate aircraft with folding wings, as would be used on aircraft carriers during the war. Again especially built for Naval Air Stations, the sides were canted to allow close parking of aircraft. Sadly these hangars have now gone but their concrete foundations and door rails do still remain.

In the next post we shall continue looking at RNAS Crail, and the huge number of squadrons that used it during its operational life. We shall look at the variety of aircraft that would operate from here, along with its post war history and its current status. It truly is the Mary Celeste of aviation.