High up in the northern most reaches of England is an airfield that has repeatedly appeared in the memoirs of many RAF and USAAF pilots. Not because it was a busy front-line station dealing with the constant battle against marauding enemy bombers, but more simply because it was a training station. However, this airfield was no ordinary training facility. It operated a large number of aircraft whose pilots played a major part in both the Normandy landings and the drive on through France and the low countries. In this, the next trail, we visit Northumberland, and a place where ground attack pilots honed their skills, perfecting the use of rockets, canon and bombs, in the destruction of enemy troop convoys, trains and tanks. The first stop on this trail is an airfield that is arguably one of Britain’s most significant airfields – RAF Milfield.

RAF Milfield.

RAF Milfield lies a short distance from the village it takes its name from, at the foot of the Cheviot hills on an area known as the Millfield Plain. It is an area steeped in history. On this site, evidence has been found of Neolithic hearths, storage pits and post holes. There is also evidence of two Bronze Age circular houses and a further three rectangular houses dating back to the ‘Dark Age’; an age that probably pre-dates the Anglo-Saxon conquest of the area from around AD 547.

This area was also the scene of many fierce and brutal battles between the English and the Scots, The Battle of Homildon Hill and the Battle of Flodden were both fought within a few miles of this very site. In both these conflicts, heavy casualties were suffered by both sides, and it is therefore, an area that is both used to war, and one that is rich in historical interest.

The Perimeter track is now the public road, parts lay visible alongside with associated dispersal pans.

As a military aviation site, Milfield came into being during the First World War. One of several such sites in the region that was used as little more than an emergency landing ground by 77 Squadron who were based further north at Edinburgh. Known at the time as Woodbridge, it would be a quiet little site that would soon disappear, quickly returning to its agricultural roots once war was over.

As a second war with Germany seemed inevitable, the need for new airfields became evermore apparent, and so the Air Ministry implemented the airfield expansion scheme. This programme developed so quickly that by 1942 there was a front line airfield opening at the rate of one every three days! As the German forces moved ever more quickly, and the Fall of France led to the Battle of Britain, the need for fresh, well-trained pilots became paramount. With home reserves drying up, the Commonwealth became an untapped source that would fill the ever-increasing void that was becoming a thorn in the side of the RAF.

Trained only in basic flying techniques, these crews had to be battle hardened and fit for action in a matter of weeks or even less. Initial training operations were mere ‘lip-service’ and recruits often had as much chance of killing themselves as they did the enemy they were intended to down. To meet this demand, numerous training stations were created, manned mainly by Operational Training Units (OTU), they were governed by the various arms of the Air Command: Fighter, Bomber, Naval, Transport etc.

At these training sites, crews would in essence, perform a ‘post-graduate’ training exercise, where they would be assembled for the first time and trained in their respective roles on the aircraft they would be expected to fly operationally. Milfield would be designated as one such station, and was initially identified as a suitable location for a bomber command site. Following requisition of the land in early 1941, the green-light for development was given, the process was put into place, and RAF Milfield was born.

Before any bomber crew would use Milfield though, it would pass from Bomber Command control over to Fighter Command whose focus would now be fighter pilots, and in particular, those specialising in both ground attack and dive bombing techniques.

As pilots came from all across the world, their training standards were some what disjointed, and so a refresher course bringing all crews up to the same standard would be required. This was a role that Milfield would fulfil. Working in conjunction with its satellite station a few miles to the east, RAF Brunton, Milfield crews would spend some 9 to 10 weeks in total on flying techniques, both solo and formation flying, with the more advanced training taking place at RAF Brunton.

Nestled between the main road and the River Till, Milfield would be built to bomber station specifications, the three runways being wood chip and concrete one of 1,400 yards and two of 1,100 Yards. During development and subsequent handover to Fighter Command though, the new Class ‘A’ airfield standard would come in to being, requiring all airfields to be built with a longer runway specification. However, being a fighter training site, these were not imposed and whilst two of the runways were extended (1,800 and 1,300 yards) they were not to the full Class A specification.

The runway threshold is still surviving, note the close proximity of the hills in the background.

As a training airfield it would be exceptionally busy. An expected turnover would be a new course starting around every 3 weeks, which would mean a considerable number of aircrew and aircraft; in excess of 100 air frames would be located here at Milfield at any one time. The primary fighter aircraft at this point would be the Hurricane with other examples including the Miles Master and Magister. To repair and maintain the aircraft, two T2 hangars were constructed with a further eight blister hangars located around the dispersal areas. Squadron dispersal huts were spread around the perimeter, with the technical area and main hangars being located to the south-eastern side. Accommodation, designed to be temporary, was dispersed over 13 sites, and would be designed to accommodate in the region of 1,650 staff, both male and female. Like many airfields though, this figure was surpassed with the actual ‘on roll’ totals varying considerably reflecting the constant movement of staff. Including the numerous support staff, it is believed that some 3,300 people were employed at Milfield at its height.

Adjacent to the airfield was the former Galewood Farm House, an old farm building used as an Officer’s mess during the airfield’s operational life. Destroyed in the 1960s, it was once part of an estate that adjoined the airfield, and was previously home to Josephine Butler. Josephine was the leader of a national women’s political campaign in Victorian England, who campaigned on behalf of prostitutes, abused and trafficked women until her death in 1906*1. Now commandeered by the military, a snooker table with lights powered by a generator was placed inside, and nearby stood the NAAFI theatre, the recreational building showing the usual films to keep the personnel entertained.

It was during this construction period that the first enemy action would occur over Milfield. On September 1st 1941, at 23:00 hrs, six bombs were dropped in the vicinity of Milfield. A crater 72 feet wide and 10 feet deep was recorded, the road was blocked and telephone lines were brought down. Also during this time, and whilst not officially open, aircraft would land at Millfield, presumably as test landings or after getting into difficulty. One of the first casualties here was that of Sgt. James B Spangler (R71573) RCAF flying Hurricane V7044 on 25th June 1941, who was “killed in the course of a training flight” whilst flying with 59 OTU. This tragic accident would be a sign of things to come.

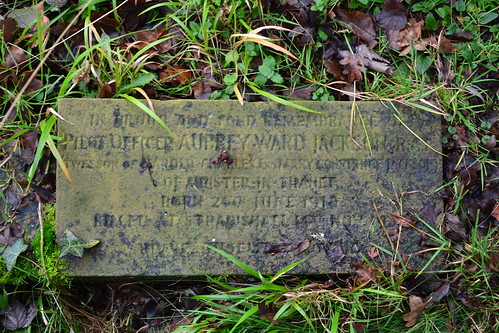

Because of the nature of training flights, accidental deaths on or around Milfield would become fairly common. These included on October 6th, 1941, Hurricane MK. I W9177 which was forced to Bellyland in a field near to Stocksfield just west of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. On 13th December 1941, Sgt. Norman Clunie Pow, (R83911) RCAF, again of 59 OTU, crashed in Hurricane P3809. Sgt. Pow was just 25 years of age and was buried some several hundred miles away next to RAF Sutton Bridge in Lincolnshire, another training station.

Sgt. Pow’s grave at Sutton Bridge.

As a training airfield, no operational front line squadrons would use Milfield, other than a detachment of 184 Sqn Hurricane IIDs between 1st December, 1942 and 1st March, 1943. The only other use of Milfield by ‘front line’ units would be as a transit base in the early post-war months.

The first full unit to arrive was that of 59 Operational Training Unit (OTU), arriving in the August of 1942.

59 OTU were originally formed at Turnhouse in December 1940, and operated amongst other things, the Hurricane, the Magister, the Fairy Battle and finally Hawker’s Tempest, all in a training capacity. After spending some five months at Crosby-on-Eden, the unit transferred to Milfield where they trained pilots in the ground attack role. As with many training stations, casualties were high, with many accidents happening through either pilot error or mechanical defects. Many of the Hurricanes used here were veterans themselves, beaten and patched up following intensive fighting in the Battle of Britain, many were long past their sell by date.

One of the first accidents to occur was that of Sgt. K. Dole, RCAF, who stalled whilst performing aerobatics – either authorised or not. His aircraft, a Hurricane MK.I ‘V7316’, MF 89 of ‘Z’ flight 59 OTU, crashed on farmland near Cornhill in August 1942. Luckily Sgt. Dole was unhurt, and the aircraft was salvaged; being repaired and sent to operations in the Middle East. The same fate however, did not fall to P/O J. Methum, who was killed in early September 1942, when his Hurricane MK.I ‘V6840’ crashed in a forced landing a few miles away to the east. The aircraft was written off in this most tragic of accidents.

The dangers of training became evermore apparent over the next few months, Saturday 27th March 1943 being particularly poor for 59 OTU with two crashes on the same day. Hurricanes Mk.I ‘W9184’ and ‘W9121’ crashing in forced landings and night landings respectively. Both pilots were killed that day; Sgt. Robert MacFadzean (s/n: 1349862) born of US resident parents, and Welshman, Sgt. Gordon Cullener (s/n: 1383311).

Four months after 59 OTU’s arrival, No 1 Specialised Low Attack Instructors School (SLAIS) would also be formed here (7th December, 1942) another unit that used the Hurricane and the Magister. One of the Chief Instructors of the School would be Squadron Leader J.H. “Ginger” Lacey DFM and Bar, a Battle of Britain Veteran who ended his career with 28 confirmed kills.

Hurricane MK.IID of No. 1 Specialised Low Attack Instructors School being refuelled and rearmed by Ground crew, including a WAAF, on a wet dispersal at Milfield. The fairings covering the two Vickers 40mm anti-tank guns beneath the wings have been removed and a warning notice hung from the barrel. (IWM CH 18134)

Low flying, in even in the relative safety of Northern England, was not immune from accidents, mishaps or misjudgements by the pilots. On 21st February 1943, Hurricane MK.II ‘HW731’ of the SLAIS hit an obstacle one mile north of Beal, the pilot escaped unharmed and after nursing the aircraft back to Milfield, it was repaired and converted for ground training purposes as ‘4616M’.

As flying training continued, so too did the number of accidents, burst tyres, engine malfunctions and fires, pilot error and collisions accounting for a wide range of them. On April 27th 1943, two Hurricanes collided in mid-air whilst performing formation flying. Both airmen, F/Sgt Davies and F/O Thompson were killed; an event that was mirrored in the following July when Hurricanes ‘P3475’ and ‘V7173’ also collided again with fatal results. New Zealander Charles Humphrey (s/n: 421056) is buried locally.

On May 1st 1943, 59 OTU transferred from 81 Group to No. 9 Group, at which point 81 Group was disbanded. No 9. took over 81’s responsibility, and it remained primarily a training arm of the Royal Air Force. For 59 OTU though, little would change.

On September 16th 1943, a B-17F-BO (42-30030) named ‘Old Ironsides‘ ran out of fuel whilst returning from La Rochelle. The pilot Lieutenant Henry J Nagorka, decided to ditch in the sea near Farne Islands, off the Northumbrian coast. The aircraft quickly filled with water and in under four minutes she had disappeared beneath the waves.

During the ditching two crewmen were lost, waist gunners: S/Sgt. Ed Christensen and S/Sgt. Claude Whitehead, whilst the tail gunner S/Sgt. Harris lost a leg. Those that survived managed to climb into a dingy and sailed to St Cuthbert’s Island where they awaited rescue. Upon being saved, they were transferred to Milfield, where they were collected by another B-17 from the USAAF. However, as Milfield was a fighter airfield and its runways hadn’t been extended to Class A specifications, there were doubts about the aircraft’s ability to get off the ground on the short space available. To overcome the problem, the hedges at the end of the runway were removed and steal planking temporarily laid, the problem never arose though as the B-17 along with its additional human cargo left Milfield safely.

B-17F ‘Old Ironsides’ 42-30030, was loss at sea on the 16th September 1943 with the loss of two men. (IWM UPL 28296)

On January 26th 1944, both 59 OTU and the SLAIS were disbanded and a new unit formed, the Fighter Leaders School (FLS). The School had its origins in 52 OTU formed at Chedworth, and was in January, created as a unit in its own right. Formed through the need for more ground attack pilots in preparation for the forthcoming invasion, it was a unit that would take on the responsibility for the majority of the RAF’s ground attack crews. One notable figure of the FLS at Milfield was Bob Doe DSO, DFC & Bar, another veteran of the Battle of Britain. He would later return to operational duties after his short stay here in Northumberland.

Using the codes HK, OQ and MF, the FLS operated a number of aircraft predominately Spitfire VBs, and Spitfire MK IXs along with a handful of other marks. It later went on to adopt the Sabre engined Typhoon IB. In total over 130 aircraft would be used by the Milfield unit, an incredible amount of aircraft on one site at any one time. Milfield continued to be in the spotlight.

It was also during this time, early 1944, that the USAAF would begin to send their pilots to Milfield to train on their ranges. With them, came a variety of US built aircraft, P-38 ‘Lightnings’, P-47 ‘Thunderbolts’ and the P-51 ‘Mustangs’. The brainchild of General Quesada, the plan was to train Ninth Air Force pilots in the art of dive bombing, skip bombing and low-level attacks, techniques that would become paramount if the push through France and on into Germany was to succeed. The arrival and increased use of Milfield by the US crews gave an indication that the impending invasion was drawing ever closer.

One of the earliest accidents for the FLS was in March of 1944, when Mohawk MK.III AR633 of 510 Squadron was hit by a Typhoon (JR509) of the Fighter Leader School on take off. Also on this day, a Spitfire MK.IIa (P8549) of the FLS tragically blew up in mid-air during a dive bombing attack on the Goswick ranges. The pilot of the Spitfire, F/Lt. Bouquen, a Belgian, was killed in the incident.

About a month later, a flight of four P47D Thunderbolts from the 366th FS (358th FG) from RAF Raydon attached to Milfield, were carrying out practice strafing attacks on a military convoy. During the climb out of the attack, one of the Thunderbolts (#42-25530), piloted by 1st Lt A. Serapiglia collided head on with Spitfire Mk 1 ‘R6762’ which was preparing to land at nearby RAF Eshott. In the collision, both pilots Sgt. Kai Knajenhjelm a 19-year-old Norwegian and Lt. Serapiglia were killed. After the investigation it was deemed that all future exercises should be performed “outside of local flying areas” of nearby airfields, something that perhaps seems obvious today, but reflects the hectic and often frantic skies over northern England in the 1940s.

A further accident to befall the Americans occurred on May 27th 1944, when a P-38 ‘Lightning’ #42-67425, of the 392nd FS, 367th FG piloted by Dueron H. Robertson, of the Ninth Air force, suffered a landing accident. The aircraft suffered major damage in the crash.

One of the benefits of attending the FLS was the diverse range not only of nationalities: Dutch, Czech, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South Africans to name but a few, but also the range of aircraft used. At the end of courses, trainees – now fully fledged fight pilots – were sometimes given the opportunity to try out other types of aircraft. An action that no doubt put the fear of God into the Station Commander who was heard to have shut his door and say “to hell with it”*2 . A number of other incidents occurred during this hectic time, which saw, by the end of December 1944, the FLS being absorbed into the Central Fighter Establishment based at RAF Wittering. Following this, the staff at Milfield all moved out, and momentarily peace prevailed once more.

Between mid December 1944 and into early January 1945, 56 OTU was reformed. Previously at RAF Sutton Bridge in Lincolnshire, it brought new aircraft, to the area, and Northumbria now reverberated to the radial engines of the Typhoon IB and the Tempest V; as four squadrons operated the aircraft using the codes FE, GF, HQ and OD. A collection of other aircraft types also graced the skies of this now highly significant airfield, Spitfires, Tiger Moths, Leopard Moths and Magisters to name but a few.

Even though the war in Europe was winding its way toward its conclusive ending, priority for aircraft was given to this purposefully created unit, and practice flights continued in earnest. The skies remained busy and accident numbers remained high. In the space of one month between mid January and mid February 1945, there were no less than 8 incidents involving aircraft from Milfield and 56 OTU. As with many incidents here, poor weather, engine failures and pilot error were the causes of many aircraft abandonment, pilot injuries and tragically deaths. In these eight incidents six involved Typhoons and two involved Tempests.

MG & Cannon Range building, one of the few remaining structures at Milfield.

March and April were similar stories, accidents, mishaps and deaths continued to plague Milfield, with pilot error accounting for a larger number of the accidents. Perhaps one of the most bizarre incidents took place on March 8th 1945 when the leader of a Spitfire squadron ‘deliberately’ attacked a Typhoon Mk.Ib ‘MP187’ of 56 OTU, killing the pilot F/O. R Smith of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The Typhoon was commonly mistaken for the Luftwaffe’s Focke Wolf 190, a formidable beast that became the scourge of the USAAF bomber formations.

The closing stages of the war didn’t bring a respite either. Saturday 12th May saw a collision between Tempests ‘EJ685’ and ‘NV759’ an event that killed an instructor pilot. Even after the war’s end, accidents continued to occur, with June, July, August and September all witnessing further deaths and incidents. August 23rd saw Typhoon ‘SW638’ collide on the ground with two other aircraft, both those struck were written off whilst the ‘offending’ aircraft was badly damaged.

At the end of the war, and over just a two-day period, the only two operational units to use Milfield would arrive, using it as a transit stop. Both 164 Squadron and 183 Squadron would arrive and depart on the same day 16 – 17th June 1945 bringing with them yet more Typhoons.

Eventually, nearly nine months after the war’s end, on February 14th 1946, 56 OTU were disbanded, but not before one final roll of the dice when the life of an RAF pilot was taken. On January 29th 1946, whilst on a “Camera Exercise” and after performing a slow roll ten miles west of Holy Island, Tempest Mk. V EJ859 piloted by F/Lt. Vincent Parker (s/n 42356) RAFVR, an Australian aged 27, dived into the ground killing him. In a cruel twist of irony, F/Lt Parker was killed after having survived as a prisoner of war since 16th August 1940. He had remained in a German POW camp until its liberation at the end of hostilities, returning to England in June 1945, his post-war, peacetime life had been shorter than his life in captivity.

The departure of 56 OTU signified the end of the RAF’s interests in Milfield, and although not a front line operational airfield, it had become a very active and played a highly significant role in fighter training and development. Used to train both new and experienced pilots, it had become one of the RAF’s top fighter pilot training stations, developing pilot’s proficiency in low-level weapons delivery techniques. No matter how dangerous the training got, crews had continued to pass through, morale had remained high and the standards were never dropped. Of the 1,200 pilots who had passed through here, many went on to make their names as the top ground attack pilots of the Second World War.

Immediately after the war, many of the accommodation huts were used to house Latvian soldiers, many staying here up until 1950. Local people were then housed in refurbished WAAF blocks before moving on to more permanent housing in the local village.

Soon after, Milfield began its decline with many of the buildings being demolished over the coming years. During the cold war era, the two T2 hangars were designated storage units for dried foods and emergency rations, thankfully a role that never had to be called into operation. Eventually the runways were dug up and removed for hardcore, quarrying took over the southern end of the airfield and much of the surface layers were removed in the process.

During the 1970s investigations were carried by Air Anglia into the possibility of commencing commuter flights to European cities, but the project failed to ‘get off the ground’ and the service was scrapped before it ever developed into anything more than investigative flights.

Now partly returning to agriculture, a small section of the airfield has been retained by the Borders Glider Club*3 . The battle to keep gliders and flying here alive, being a long and difficult one. Through this small organisation, that operates only at the weekends, the spirit of flying lives on, and Milfield continues to fight for survival, a fight that has been both emotive and historically significant in the battle for the skies over Britain. The T2s have now gone as has virtually all the remaining buildings. A stone statue built by an Italian POW who was employed on the local farm, stands on private land, marking what was the official entrance to the airfield during the war years, it is clearly visible from the road side.

One of two sculptures, one made by an Italian POW, the second copied by an RAF serviceman.

Located four miles north-west of Wooler and Visiting today, there is some evidence of the former airfield left. Small sections of the perimeter track are now the public road, but alongside the road, the remainder of the track can just still be seen. The north-western end of the runway is also visible as are a small collection of dispersal pans. The MG & Cannon Range building still stands, minus its roof it is rapidly decaying, it has a very short life left.

Interestingly, as a training airfield, Milfield used both a Fisher Front Turret Trainer and Hawarden Trainer, a simulation trainer that used the fuselage of a Spitfire to train pilots in interception techniques. A model suspended from the ceiling up to 60 feet away from the pilot could be moved forwards or backwards by operating the opposite movement of the Spitfire’s throttle. As the Spitfire ‘accelerated’ the model moved backwards along a rail, rather similar in design to a 1970’s child’s toy. During these sessions a range of flying skills could be tested, interception and aircraft recognition, throttle control and cockpit procedures included. A primitive method that was state of the art in 1941. Sadly neither of these exist today.

Two memorials are located at this site, the first in a public car park to the western end of the airfield, next to the Maelmin heritage trail. The second is located outside the club house of the Borders Gliding Club, approximately on the site of the former watch office, itself no longer there. This memorial was commissioned by the club entirely through donations and is their way of acknowledging the sacrifice of those who flew from Milfield.

Interestingly a comment made by visitor Reginald Hall states that his wife’s uncle, David Harrison, (born in Gateshead in 1911) was stationed here to “strip out as much non-essential equipment as possible from the planes (he said principally Spitfires) to lighten their weight and so permit a greater quantity of fuel to be carried, sufficient to enable the return flights from Milfield to Scandinavia that were required for photographic reconnaissance“. Unfortunately the exact date of this Reg is unsure of, but I thank him for his comment which can be read in full in the comments below.

Milfield is arguably one of the most significant airfields of the Second World War, many Spitfire, Hurricane and Typhoon pilots quote it in their memoirs, their time here short but memorable. Here ground attack pilots cut their teeth, low-level strafing and dive bombing techniques being honed to absolute perfection. The battle for Europe would certainly have been more difficult were it not for those daring young men who passed through this remote but historically important airfield.

After we leave Milfield, we head east, toward the coast and the satellite of Milfield. A small airfield, it too played a major part in the development of ground attack crews and it too saw many accidents and losses through its training programme. From here we go to RAF Brunton.

Sources and Further Reading.

*1 A website tells the story of Josephine Butler’s life, and another has photos of Galewood farm-house.

*2 Dunn, W.R., “Fighter Pilot: The First American Ace of World War II“, 1996, The University Press of Kentucky, Page 118.

*3 Border flying club website

The Friends of Berwick and District Museum and Archives website provide information about the archaeological history of Milfield.

A book has been published about RAF Milfield, a complementary website gives fabulous personal detail of life at the airfield and is well worth a visit.

Photos of those stationed at Milfield can be seen through the BGC Flckr account.