In this next trail we turn westward and head to the Midlands towards Nottingham and Leicester. Here we take in an airfield that was part of the RAF’s Bomber Command, and whilst it is an airfield that saw only a small number of squadrons operating from it, it nonetheless has a very significant story to tell. Now a successful industrial park, much of the site remains – albeit behind a security gate and fencing. This airfield was home to both the RAF and the USAAF and played an important part in the fight against Nazi Germany. Today we visit the former airfield RAF Bottesford.

RAF Bottesford (Station 481)

RAF Bottesford was built in the period 1940 / 41 by the major airfield builder George Wimpey & Co. Ltd. It was known more locally as Normanton after the small village that lies on the south-western corner of the site, and although a Leicestershire airfield, it actually straddles both Leicestershire, Nottingham and Lincolnshire. As a new bomber airfield, it was the first in the area to be built with concrete surfaces, a welcome break from the problematic grassed surfaces that Bomber Command had been fighting against before.

In 1941 Bottesford would open under the control of No. 5 Group, a group formerly headed by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, who had seen the group carry out anti-shipping sweeps over the North Sea and leaflet drops over Germany. Now under the guidance of Air Chief Marshal Sir John Slessor, No. 5 Group was able to muster a considerable number of heavy bombers capable of reaching Germany’s heartland.

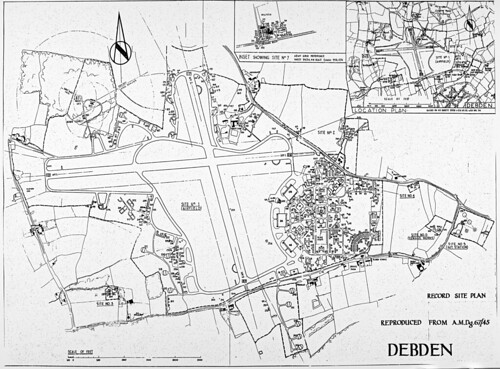

As a bomber airfield Bottesford had a wide range of technical buildings, three concrete runways, one of 2,000 yds (after being extended) and two just short of 1,500 yds, all 50 yds wide and linked by a perimeter track. The technical site with its various support buildings lay to the north-west of the airfield with the bomb site to the east, and accommodation areas dispersed to the north-east beyond the airfield perimeter.

Bottesford would accommodate around 2,500 personnel of mixed rank, both male and female, in conditions that were often described as ‘poor’, the site suffering from extensive rain and lack of quality drainage as the Operational Records would show *1.

Around the airfield there would eventually be 50 dispersals, half of these being constructed initially as ‘frying pan’ hardstands, and then with the introduction of the improved ‘spectacle hardstand’, this number was doubled by 1945.

Aircraft maintenance would initially be in four hangars, but these were also increased to ten in total, giving a mix of T2 and B1 designs. An unusual design feature of Bottesford was that some of these dispersals, and later hangars, were across a public road and, like RAF Foulsham (Trail 22), a gate system operated by RAF Police would allow the road to be closed off when aircraft were moved into or out of the area. The airfield would therefore, undergo quite a major change during its operational life.

RAF photo reconnaissance photo taken on 8 June 1942. Compare this to the photograph taken three years later (below)*2

Bottesford 1945 *3

Only three operational front line RAF units would operate from Bottesford, the first being 207 Squadron flying the Avro Manchester, arriving on November 17th 1941, the same month as production of the Manchester ceased. Their arrival would also coincide with the arrival of 1524 (BEAM Approach Training) Flight operating the Airspeed Oxford.

207 Sqn were reformed as a new squadron at the beginning of November 1940, taking on the ill-fated Avro Manchester MK.I, before arriving here at Bottesford a year later. The first squadron to operate the type, they were soon to discover it had major issues, and so poor was the Manchester, that by the Spring of 1942 it was being withdrawn, replaced by its more successful sister the Lancaster. After its promising introduction into Bomber Command in late 1940, it became clear that the Manchester was going to become a troublesome aircraft. With engine seizures often followed by fires, it was very much under-powered even though it had what were in essence, two V12 engines mounted in one single engine. Bearing failures led to engines failing, and already working at its limits, the Rolls-Royce Vulture engine was not able to keep the Manchester aloft without great skill from the crew.

After a period of bedding in and conversion of the crews to the new Manchester, the new year at Bottesford would start off badly, seeing the first casualty for 207 Sqn, on the night of 9th January 1942. On this mission, Manchester MK.I L7322 piloted by F/O G Bayley, would crash after being hit by flak on operations to Brest. There were 151 aircraft on this mission, with this aircraft being the only causality in which only three of the crew’s bodies were ever recovered.

The transition from the Manchester to the Lancaster would not be straight forward for 207 Sqn. Whilst on training flights, Lancaster MK.I ‘EM-G’ R5501 would collide in mid-air with a Magister from RAF Cranwell, four crewmen would lose their lives along with the pilot of the Magister. Then on the 8th April, a second Lancaster would suffer problems when ‘EM-Z’ R5498 experienced fuel starvation in both starboard engines causing them to cut out. The aircraft crashed close to Normanton Lodge on the north-south boundary on approach to Bottesford’s main runway. Fortunately no one was seriously injured in the accident.

A third training accident occurred on the night of May 24th 1942, when Lancaster R5617 hit the ground in poor visibility near to Tavistock in Devon. In the resultant crash, four of the crew were killed whilst two further crewmen were injured. It was proving to be a difficult transition for the crews of 207 Sqn.

The first operational loss of a 207 Sqn Lancaster came on the night of June 3rd / 4th, when ‘EM-Y’ R5847 was shot down whilst on a mission to Bremen in north-west Germany. During the flight, the aircraft were attacked by German night fighters. As a result a number of aircraft from various squadrons were lost, including this one flown by pilot W/O C. Watney, who along with all his crew, were killed.

With the last mission by a Manchester taking place on the night of June 25th / 26th, 1942 would be a difficult year for 207 Sqn, losing four Manchesters and twenty-five Lancasters, which when added to the twenty Manchesters lost in 1941, proved that things were not going well for the 5 Group squadron at Bottesford.

Sgt. Harold Curson (s/n: 537658) was killed in a bizarre accident at Bottesford when a Manchester landed on top of a Lancaster destroying the aircraft and killing three of its crew.

Perhaps one of the most bizarre accidents to happen at Bottesford, occurred on August 6th 1942, when Manchester L7385 landed very badly. Somehow, the aircraft ended up on top of a Lancaster, R5550 who was also engaged in training operations. The accident was so severe, that two of the crew in the Manchester and three of the crew in the Lancaster were killed. The remaining five crewmen, whilst not killed in the accident, all sustained various degrees of injury.

Then in September 1942, 207 Sqn were transferred from Bottesford to nearby Langar, the satellite airfield for Bottesford. This would be the first of many moves that would last into early 1950 when the squadron was finally disbanded whilst operating the Avro Lincoln. The squadron’s tie with Avro had finally come to an end (207 Sqn would reform several times eventually being disbanded in the mid 1980s).

The October / November 1942 then saw two further Bomber Command squadrons move into this Leicester airfield, those of 90 Squadron and 467 Squadron.

Reformed here after being disbanded and absorbed into 1653 HCU the previous February, 90 Sqn brought with them the other great heavy bomber, the Stirling.

An enormous aircraft, the Stirling also failed to live up to its promise, suffering from a poor ceiling and often being targeted by fighters when in mass formations. The Stirlings were eventually pulled out of front line operations and moved to transport and SOE operations, such were their high losses.

At the end of the year once the squadron was fully manned and organised, No. 90 Sqn departed Bottesford taking the Mk.Is to RAF Ridgewell, where they continued on in the bomber role. The only casualty for 90 Sqn during this short time occurring on the very same day they moved when ‘WP-D’ BK625 crash landed at Ridgewell airfield.

Also during the month of November 1942, on the 24th, 467 Squadron (RAAF) joined 90 Sqn, in a move that saw the return of the Lancaster MK.I and MK.III, these crews must have been the envy of those who struggled with the mighty Stirling in their sister unit. Formed on the 7th November at RAF Scampton under the command of W/Cdr. C. Gomm DFC No. 5 Group, 467 Sqn were another short-lived squadron eventually being disbanded on September 30th 1945 at Metheringham airfield in Lincolnshire.

In the first days of their formation there were initially sixteen complete aircrews, divided into two flights: ‘A’ commanded by Acting S/Ldr. D Green DFC and ‘B’ Flight with Acting S/Ldr. A. Pappe DFC. As yet though, they had an insufficient number of aircraft to accommodate all the crews.

After arriving at Bottesford, 467 Sqn battled with lack of equipment and poor weather which hindered both training and flying activities. A number of dances were held to make the Australians and New Zealand crews “feel at home”, and a visit was made by Air Marshal Williams (RAAF). At the end of the month, aircraft numbers totalled just seven.

By the end of December new aircraft had been delivered and the Lancaster total stood at nineteen, but poor weather continued to hamper flying. Early January saw the first sign of any operational action at Bottesford, which occurred on the night of January 2nd / 3rd 1943. Five crews were assigned to a ‘Gardening’ sortie, laying mines, which excited the ground crews who were keen to see their aircraft finally participating in operations. It wouldn’t be until January 17th / 18th that 467 Sqn would finally venture into German territory laden with bombs. A mission that took them to the heart of Germany and Berlin.

One of Bottesford’s hangars in use today.

With great excitement nine Australian crews, who were keen to show what they were capable of, took off from Bottesford to hit the target. The mission was considered a ‘disappointment’, damage to the target being very light due to both haze and lack of good radar. Target Indicators were used for the first time on this mission and it was the first all four-engined sortie. On their return flight, Sgt. Broemeling, the rear-gunner of F/Lt. Thiele’s crew was found unconscious, he had suffered from oxygen starvation and even after diving the aircraft to a safe breathing height and giving artificial resuscitation, he was declared dead on arrival at Bottesford.

A second night saw 187 RAF bombers from No. 1, 4 and 5 Groups in a subsequent raid that, like the previous night, also resulted in poor results. Bombing saw little damage on the ground but twenty-two aircraft were lost. One of these aircraft being from 467 Sqn, that of Lancaster ‘PO-N’ W4378, which was piloted by a New Zealander, Sgt. K Aicken. Sgt Aicken had been one of the original pilots at 467’s formation. All seven crewmen from ‘PO-N’ were killed that night.

The next casualties would occur a month later, in a mission that saw 338 RAF heavies attack the port of Wihelmshaven in northern Germany. With the mission considered a ‘failure’, outdated maps were blamed, pathfinders marking the target area inaccurately as a result. The raid would also be notable for the loss of two Bottesford Lancasters; ED525 and ED529. On board the second aircraft were two crewmen Sgt. Robert Sinden (s/n: 577701) and Sgt. Derek Arnold Booth (RAFVR) (s/n: 1378781) who were just 18 and 17 years old respectively – the youngest crewmen to lose their lives in Bomber Command’s campaign of 1943. None of the fourteen men were ever found, their aircraft lost without trace.

A year after their arrival 467 Sqn then departed Bottesford heading for RAF Waddington, a point at which the RAF handed Bottesford over to the Americans in answer to their call for airfields to support the forthcoming invasion of the continent. 467 Sqn would go on to fight under Bomber Command, and in that month a special Lancaster would join the Sqn, that of R5868 ‘PO-S’ which went on to be the first Lancaster to reach the 100 mission milestone completing a total of 137 before the war’s end. She sat outside RAF Scampton as a gate guard after the war but has thankfully ended her days as the centre piece of the Bomber Command Hall at the RAF Museum in Hendon.*4

‘S-Sugar’ a former 467 Sqn Lancaster stands in the RAF Museum, Hendon. Note the incorrect Spelling of ‘Hermann’ beneath the quote.

As one of a cluster in the area (North Witham (Trail 3), Spanhoe (Trail 6), Barkston Heath and Langar amongst others), Bottesford would become a home to the Glider units of the US Troop Carrier Command (TCC).

The airfield (renamed Station 481) would become the headquarters of the 50th Troop Carrier Wing (TCW), Ninth Air Force, and used as a staging post for new C-47 units arriving from the United States. The 50th remained here at Bottesford until April 1944 at which point they moved south to Exeter in their final preparations for the Normandy invasion.

This deployment would see a number of American units arrive, be organised and transfer to their own bases elsewhere, these included the eight squadrons of the 436th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) and the 440th Troop Carrier Group (TCG).

The 436th TCG were made up of the four squadrons:79th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS), 80th TCS, 81st TCS and 82nd TCS, all flying C-47 aircraft. The Group was only one year old when they arrived at Bottesford, and their introduction to the war would be a baptism of fire.

The cramped barracks of the 436th TCG and 440th TCG at Bottesford. (IWM – FRE 3354)

Whilst primarily training and organising themselves at Bottesford they would go on to take part in the Normandy invasion, dropping paratroops early in the morning of June 6th 1944 into the Normandy arena. In the afternoon, they returned with gliders, again dropping them behind enemy lines to supply and support those already fighting on the ground. A further trip the following morning saw the group awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation (DUC) for their action over the Normandy landing zones. Before the war’s end the 436th would take part in four major allied airborne operations, dropping units of both the 82nd and the 101st Airborne.

The 440th, like the 436th, were a very young unit, only being activated the previous July, and like the 436th, their introduction would be a memorable one. Dropping paratroops of the 101st Airborne into Carentan on D-Day, followed by fuel, food and ammunition the next; for their action they too were awarded a DUC. The 440th would also take part in the Battle of the Bulge supplying troops at Bastogne and later the crossing of the Rhine.

Whilst both units were only here at Bottesford a short time, they undoubtedly played a major part in the Allied invasion and all major airborne battles on the continent, a point that Bottesford should be remembered for.

The 436th moved to Membury whilst the 440th moved to Exeter in a mass move with the 50th TCW. After this, the US brought in a Glider repair and maintenance unit, who only stayed here for a short time before they too departed for pastures new. This then left Bottesford surplus to American requirements, and so in July 1944 it was handed back to the RAF and 5 Group once more.

This transfer would see the last flying unit form here at Bottesford – the death knell was beginning to ring its ghostly tones. The RAF’s 1668 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) formed on the 28th, brought back the heavy bomber, the Lancaster MK.I. Working with the HCU were the 1321 Bomber (Defence) Training Flight consisting of mainly Beaufighter and Spitfire aircraft, who operated here until 1st November 1944 when they were absorbed into 1668 and 1669 HCUs. The HCU used these aircraft for fighter affiliation tasks and heavy bomber training.

As a training unit there would be many accidents, either due to aircraft problems or pilot error, including the first major accident on 12th December 1944 where fire tore through the port wing of Lancaster MK.III JA908. Diverted to East Kirkby the Lancaster attempted a landing but damaged a wheel, and had to crash-land in a field near to the airfield. Whilst no-one was killed in the crash, eight aircrew were injured in the resultant fire.

In the August 1945, the HCU moved to Cottesmore and there was no longer a need for Bottesford as an operational airfield. Surplus to requirements it was placed into care and maintenance, and used to store surplus equipment including ammunition before being closed and sold to the farmer who’s been using it since 1962.

As with all RAF / USAAF airfields a number other flying units operated from Bottesford, maintenance units, RAF squadrons and Glider units all played their part in its rich tapestry of wartime history. A history that provided one of the largest numbers of hangars collectively, and one that saw many young men come and go, many not coming back at all.

Today Bottesford is a thriving industrial and agricultural park, the farmer using large parts of it but the technical site being used by a number of industrial companies. The hangars are still present and in use, as are the runways now used for storage of vehicles rather than Lancasters, Stirlings, Manchesters or C-47s. The watch office has been refurbished and is used as offices, and several of the original buildings still remain in various states of disrepair. A flag of remembrance was hoisted outside the office in May 1995 and veterans have visited the site to pay their respects.

With access to the site through a security gate, you are left with some poor views from public roads, but the local church does have a small number of graves and a memorial which includes a book of remembrance.

Bottesford may have only been in existence for a short period, but it saw many aircraft and many crews, a mix of international airmen who brought new life to this small village on the border of three counties.

A book of remembrance sits in the local church St. Mary the Virgin along with a small number of graves.

Links and sources

*1 AIR\271930\1 Operational Record Book 467 RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) Summary of Events (National Archives).

*2 Source Imperial War Museum photo ref: RAF_HLA_590_V_6004

*3 Source Imperial War Museum photo ref: RAF_106G_LA_203_RP_3093

*4 The AVRO Heritage Museum Website has details of ‘S for Sugar’ and her journey to Hendon.

Defence of the Realm, Tony Wilkins takes a detailed look at the Avro Manchester.

The Bottesford Living History Group have a detailed website with photographs and personal accounts and is worth visiting.