Trail 44 takes a look at the aviation highlights of the North Kent Coast in the small town of Herne Bay and its neighbour Reculver. It was here, on November 7th 1945, that the World Air Speed record was set in a ‘duel’ between two Gloster Meteors, as they raced across the Kent Sky.

On that day, two Meteor aircraft were prepared in which two pilots, both flying for different groups, would attempt to set a new World Air Speed record over a set course along Herne Bay’s seafront. The first aircraft was piloted by Group Captain Hugh Joseph Wilson, CBE, AFC (the Commandant of the Empire Test Pilots’ School, Cranfield); and the second by Mr. Eric Stanley Greenwood O.B.E., Gloster’s own chief test pilot. In a few hours time both men would have the chance to have their names entered in the history books of aviation by breaking through the 600mph air speed barrier.

The event was run in line with the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale‘s rules, covering in total, an 8 mile course flown at, or below, 250 feet. For the attempt, there would be four runs in total by each pilot, two east-to-west and two west-to-east.

With good but not ideal weather, Wilson’s aircraft took off from the former RAF Manston, circling over Thanet before lining his aircraft up for the run in. Following red balloon markers along the shoreline, Wilson flew along the 8 mile course at 250 feet between Reculver Point and Herne Bay Pier toward the Isle of Sheppey. Above Sheppey, (and below 1,300 ft) Wilson would turn his aircraft and line up for the next run, again at 250ft.

Initial results showed Greenwood achieving the higher speeds, and these were eagerly flashed around the world. However, after confirmation from more sophisticated timing equipment, it was later confirmed that the higher speed was in fact achieved by Wilson, whose recorded speeds were: 604mph, 608mph, 602mph and 611mph, giving an average speed of just over 606mph. Eric Greenwood’s flights were also confirmed, but slightly slower at: 599mph, 608mph, 598mph and 607mph, giving an overall average speed of 603mph. The actual confirmed and awarded speed over the four runs was 606.38mph by Wilson*1.

The event was big news around the world, a reporter for ‘The Argus*2‘ – a Melbourne newspaper – described how both pilots used only two-thirds of their permitted power, and how they both wanted permission to push the air speed even higher, but both were denied at the time.

In the following day’s report*3, Greenwood described what it was like flying at over 600 mph for the very first time.

As I shot across the course of three kilometres (one mile seven furlongs), my principal worry was to keep my eye on the light on the pier, for it was the best guiding beacon there was. On my first run I hit a bump, got a wing down, and my nose slewed off a bit, but I got back on the course. Below the sea appeared to be rushing past like an out-of-focus picture.

I could not see the Isle of Sheppey, toward which I was heading, because visibility was not all that I wanted.

At 600mph it is a matter of seconds before you are there. It came up just where I expected it. In the cockpit I was wearing a tropical helmet, grey flannel bags, a white silk shirt, and ordinary shoes. The ride was quite comfortable, and not as bumpy as some practice runs. I did not have time to pay much attention to the gauges and meters, but I could see that my air speed indicator was bobbing round the 600mph mark.

On the first run I only glanced at the altimeter on the turns, so that I should not go too high. My right hand was kept pretty busy on the stick (control column), and my left hand was. throbbing on the two throttle levers.

Greenwood went on to describe how it took four attempts to start the upgraded engines, delaying his attempt by an hour…

I had to get in and out of the cockpit four times before the engines finally started. A technical hitch delayed me for about an hour, and all the time I was getting colder and colder. At last I got away round about 11.30am.

He described in some detail the first and second runs…

On the first run I had a fleeting glance at the blurred coast, and saw quite a crowd of onlookers on the cliffs. I remembered that my wife was watching me, and I found that there was time to wonder what she was thinking. I knew that she would be more worried than I was, and it struck me that the sooner I could get the thing over the sooner her fears would be put at rest.

On my first turn toward the Isle of Sheppey I was well lined up for passing over the Eastchurch airfield, where visibility was poor for this high-speed type of flying. The horizon had completely disappeared, and I turned by looking down at the ground and hoping that, on coming out of the bank, I would be pointing at two balloons on the pier 12 miles ahead. They were not visible at first.

All this time my air speed indicator had not dropped below 560 mph, in spite of my back-throttling slightly. Then the guiding light flashed from the pier, and in a moment I saw the balloons, so I knew that I was all right for that.

On the return run of my first circuit the cockpit began to get hot. It was for all the world like a tropical-summer day. Perspiration began to collect on my forehead. I did not want it to cloud my eyes, so for the fraction of a second I took my hands off the controls and wiped the sweat off with the back of my gloved hand. I had decided not to wear goggles, as the cockpit was completely sealed. I had taken the precaution, however, of leaving my oxygen turned on, because I thought that it was just that little extra care that might prevent my getting the feeling of “Don’t fence me in.”

Normally I don’t suffer from a feeling of being cooked up in an aircraft, but the Meteor’s cockpit was so completely sealed up that I was not certain how I should feel. As all had gone well, and I had got half-way through the course I checked up my fuel content gauges to be sure that I had plenty of paraffin to complete the job.

I passed over Manston airfield on the second run rather farther east than I had hoped, so my turn took me farther out to sea than I had budgeted for. But I managed to line up again quite satisfactorily, and I opened up just as I was approaching Margate pier at a height of 800 feet. My speed was then 560 mph.

Whilst the first run was smooth, the second he said, “Shook the base of his spine”.

This second run was not so smooth, for I hit a few bumps, which shook the base of my spine. Hitting air bumps at 600 mph is like falling down stone steps—a series of nasty jars. But the biffs were not bad enough to make me back-throttle, and I passed over the line without incident, except that I felt extremely hot and clammy.

After he had completed his four attempts, Greenwood described how he had difficulty in lowering his airspeed to enable him to land safely…

At the end of my effort I came to one of the most difficult jobs of the lot. It was to lose speed after having travelled at 600 mph. I started back-throttling immediately after I had finished my final run, but I had to circuit Manston airfield three times before I got my speed down to 200mph.

The two Meteor aircraft were especially modified for the event. Both originally built as MK.III aircraft – ‘EE454’ (Britannia ) and ‘EE455’ (Yellow Peril) – they had the original engines replaced with Derwent Mk.V turbojets (a scaled-down version of the RB.41 Nene) increasing the thrust to a maximum of 4,000 lbs at sea level – for the runs though, this would be limited to 3,600 lbs each. Other modifications included: reducing and strengthening the canopy; lightening the air frames by removal of all weaponry; smoothing of all flying surfaces; sealing of trim tabs, along with shortening and reshaping of the wings – all of which would go toward making the aircraft as streamlined as possible.

EE455 ‘Yellow Peril’ was painted in an all yellow scheme (with silver outer wings) to make itself more visible for recording cameras.*4

An official application for the record was submitted to the International Aeronautical Federation for world recognition. As it was announced, Air-Marshal Sir William Coryton (former commander of 5 Group) said that: “Britain had hoped to go farther, but minor defects had developed in ‘Britannia’. There was no sign of damage to the other machine“, he went on to say.

Wilson, born at Westminster, London, England, 28th May 1908, initially received a short service commission, after which he rose through the ranks of the Royal Air Force eventually being placed on the Reserves Officers list. With the outbreak of war, Flt. Lt. Wilson was recalled and assigned as Commanding Officer to the Aerodynamic Flight, R.A.E. Farnborough. A year after promotion to the rank of Squadron Leader in 1940, he was appointed chief test pilot at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (R.A.E.) who were then testing captured enemy aircraft. He was promoted to Wing Commander, 20th August 1945, retiring on 20th June 1948 as a Group Captain.

Eric Greenwood, Gloster’s Chief Test Pilot, was credited with the first pilot to exceed 600 miles per hour in level flight, and was awarded the O.B.E. on 13th June 1946.

His career started straight from school, learning to fly at No. 5 F.T.S. at Sealand in 1928. He was then posted to 3 Sqn. at Upavon flying Hawker Woodcocks and Bristol Bulldogs before taking an instructors course, a role he continued in until the end of his commission. After leaving the R.A.F., Greenwood joined up with Lord Malcolm Douglas Hamilton (later Group Captain), performing barnstorming flying and private charter flights in Scotland.

Greenwood then flew to the far East to help set up the Malayan Air Force under the guise of the Penang Flying Club. His time here was adventurous, flying some 2,000 hours in adapted Tiger Moths. His eventual return to England saw him flying for the Armstrong Whitworth, Hawker and Gloster companies, before being sent as chief test pilot to the Air Service Training (A.S.T.) at Hamble in 1941. Here he would test modified U.S. built aircraft such as the Airocobra, until the summer of 1944 when he moved back to Gloster’s – again as test pilot.

It was whilst here at Gloster’s that Greenwood would break two world air speed records, both within two weeks of each other. Pushing a Meteor passed both the 500mph and 600mph barriers meant that the R.A.F. had a fighter that could not only match many of its counterparts but one that had taken aviation to new record speeds.

During the trials for the Meteor, Greenwood and Wilson were joined by Captain Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, who between them tested the slimmed-down and ‘lacquered until it shone’ machine, comparing drag coefficients with standard machines. Every inch of power had to be squeezed from the engine as reheats were still in their infancy and much too dangerous to use in such trials.

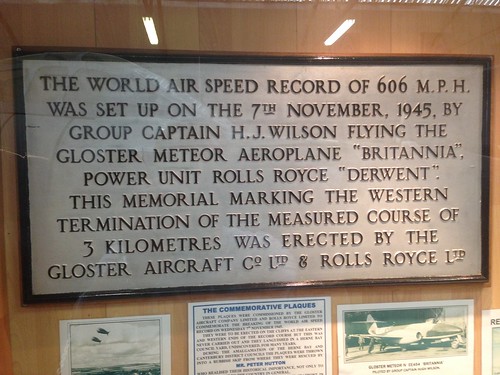

To mark this historic event, two plaques were made, but never, it would seem, displayed. Reputed to have been saved from a council skip, they were initially thought to have been placed in a local cafe, after the cliffs – where they were meant to be displayed – collapsed. The plaques were however left in the council’s possession, until saved by an eagle-eyed employee. Today, they are located in the RAF Manston History Museum where they remain on public display.

To mark the place in Herne Bay where this historic event took place, an information board has been added, going some small way to paying tribute to the men and machines who set the world alight with a new World Air Speed record only a few hundred feet from where it stands.

Part of the Herne Bay Tribute to the World Air Speed Record set by Group Captain H.J. Wilson (note the incorrect speed given).

From Herne Bay, we continue on to another trail of aviation history, eastward toward the coastal towns of Margate and Ramsgate, to the now closed Manston airport. Formerly RAF Manston, it is another airfield that is rich in aviation history, and one that closed with huge controversy causing a great deal of ill feeling amongst many people in both the local area and the aviation fraternity.

Sources and Further Reading.

*1 Guinness World Records website accessed 22/8/17.

*2 The Argus News report, Thursday November 8th 1945 (website) (Recorded readings quoted in this issue were incorrect, the correct records were given in the following day’s issue).

*3 The Argus News report, Thursday November 9th 1945 (website)

*4 Photo from Special Hobby website.

The RAF Manston History Museum website has details of opening times and location.

The Manston Spitfire and Hurricane Memorial museum website has details of opening times and location.