Laying quietly between the airfields at Matlaske and Swannington is another one of Addison’s 100 group’s small collection. An airfield that not only saw a variety of makes and models, but a range of nationalities as well, each having a remarkable story to tell. In the second part of Trail 34, we travel a few miles south and visit RAF Oulton.

RAF Oulton.

RAF Oulton in 1946, taken from the north. (IWM)

Although an RAF base, Oulton was also home to the heavy American bombers the B-17 and B-24. However, they were not used in their natural heavy bomber role, but a more secret and sinister one.

Initially built as a satellite for the larger bomber base at Horsham St. Faith, Oulton originally only had grass runways. It would later, in 1942, be upgraded to class ‘A’ standard, which would require the construction of three concrete runways, a new tower and bomb store and upgrading to the technical site. Runway 1 (2000 yds) ran east-west, runway 2 (1,400 yds), north-east to south-west, and runway 3 ran approximately north-south and was also 1,400 yds. All were the standard 50 yards wide and would be connected by thirty-two loop style hardstands and eleven pan style hardstands. Uncommonly, Oulton would also have four T2 hangars (three to the eastern side and one to west, two of which would later hold Horsa gliders) and a further blister hangar.

The majority of the technical area was to the eastern side of the airfield next to the main entrance and along side Oulton Street. The two bomb stores were located to the north and western sides of the airfield well away from personnel and aircraft as was common. The first of the two towers, was built to drawing 15898/40, which combined the tower and crew rooms; the second built later to drawing 12779/41 (adapted to the now common 343/43) brought the airfield in line with other Class ‘A’ airfields.

One of the huts used for agricultural purposes today.

Throughout the war personnel accommodation utilised the grand and audacious Blickling Hall. A seventeenth century building that stands in a 4,777 acre estate that once belonged to the family of Anne Boleyn. Owned more recently by Lord Lothian, he famously persuaded Churchill to write to Roosevelt declaring Britain’s position and poor military strength. Lord Lothian was a great entertainer dining with many notable people including Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s foreign Policy advisor and close friend. A number of other notable events took place at Blickling, including, in early 1945, Margaret Lockwood raising eyebrows when she and James Mason arrived to film ‘The Wicked Lady’ .

In the early 1940s, the hall was requisitioned by the RAF, officers were billeted inside the ‘wings’ whilst other ranks were put up in Nissen huts within the grounds. The lake was used for Dingy training and the upper floors allowed for baths albeit with cold water! In total some 1,780 personnel could be housed in and around the estate.

For the first two years between 1940 and 1942, Oulton airfield was the home to Blenheims, Hudsons and Beaufighters, each undertaking a light bombing or anti-shipping role as part of 2 Group.

First came 114 sqn on August 10th 1940 with Blenheim IVs. Apart from a small detachment at Hornchurch, they stayed here until the following March whereupon they moved to Thornaby. Their most notable mission was the mid-December attack on Mannheim, an attack that would signify the start of the RAF’s ‘area’ bombing campaign. A short spell of three months beginning April 1941 by 18 Sqn, preceded their return later in November and then subsequent move to Horsham St Faith.

Like many airfields during this time, units moved around and it was no different for 139 Sqn. With their Blenheims and later Hudsons, they would leapfrog between Horsham St. Faith and Oulton throughout 1941 only to disband and reform returning in 1942 with Mosquito IVs.

A few buildings remain on the site, many are fighting a losing battle with nature. The main entrance to the airfield is just to the right of this building.

It was during this time in late 1941 that Hudson conversion flight 1428 would be formed at Oulton with the sole job of training crews on the Hudson III. They would remain here until the following May, at which point they were disbanded.

The re-establishment of 236 Sqn in July 1942 with Beaufighter ICs meant Oulton performed as part of Coastal Command for a short time. The success of 236 in torpedo strikes, led to a new wing being formed at North Coates with 236 leading the way, they departed taking their Beaufighters with them. This left a vacancy, that would soon be filled with a new twin-engined model, the Boston III and 88 Squadron.

88 Sqn were split over 6 different airfields before being pulled together here at Oulton. They retained two of these detachments, one at RAF Ford and the other at RAF Hurn, and their arrival and start of operations at Oulton, would be tarnished with sadness.

On October 31st 1942, a month after they arrived, ground crews were unloading a 250lb bomb from 88 Sqn Boston ‘W8297’ when it suddenly went off. The resultant explosion destroyed the Boston and killed six members*1 of the ground crew. The youngest of these, AC2 K. F. Fowler, was only 19.

After having suffered serious losses in France whilst claiming the first RAF ‘kill’ of the war, they were the first unit to fly the new Boston, and would continue to undertake dangerous daylight intruder operations. Flying daring, low-level missions, they would attack shipping and coastal targets before supporting the allied advance on D-day. Their most famous attack was the renowned bombing of the Philips works in Eindhoven, which resulted in the loss of production for six months following the raid. Ninety-three aircraft took part in the raid, all flying beyond the reach of any fighter escort, a factor that no doubt resulted in the heavy casualties sustained by 2 Group on that mission*2 .

Two Nissen huts would have been next to this building, and according to the site map, it was part of the rubber store.

In March 1943, the Boston IIIs left and Oulton passed to Addison’s 100 group. As with many other airfields in this part of Norfolk, 100 group were using them to fly missions investigating electronic warfare and radio counter measures. This move to 100 Group would bring a major change for Oulton.

The now satellite of Foulsham would soon be seeing larger and heavier aircraft in the form of the American Fortress I (B-17E), II (F), III (G) and Liberator VI (B-24H). This change required extensive upgrading; the construction of hard runways, updating of the accommodation, new technical buildings and a second, updated tower, along with further storage facilities. The airfield was closed throughout the operation, and with the completion in May 1944 operations could begin almost immediately.

Both USAAF and RAF crews moved in. 1699 Flight were providing conversion for crews to fly the heavy bombers for their parent Squadron 214 Sqn, whilst the American 803rd BS, 36th BG flew radio-countermeasures in their B-17s and later B24s. This move here allowed their own parent station RAF Sculthorpe, to also be extensively redeveloped.

The Americans stayed for three months whilst their work was undertaken, but the RAF units remained until the end of the war. After 1699 Flt. had completed conversions, 214 changed Fortress IIs for IIIs and flew these until disbandment on July 27th 1945.

On August 23rd 1944, 223 Sqn reformed at Oulton. Having previously been flying the twin-engined Baltimore, the new unit would have to get used to much larger aircraft very quickly, a task they commanded with relative ease. They flew the heavier Liberator IVs, and Fortress IIs and IIIs until their final disbandment a year later.

Both 214 and 223 flew the heavy bombers now bristling with electronics. Using a range of electronic gadgetry such as ‘window’ ,’H2S’ and ‘Mandrel’, they had their front turrets painted over or removed and electronic equipment added. ‘Window‘ chutes were installed in the fuselage of the aircraft and a heavy secrecy enveloped the airfield.

The winter of 1944 proved to be one of the worst for many years, crews worked hard in the snowy environment, relaxing where they could at the nearby pubs, one nicely placed next to Blickling Hall and the other directly opposite the entrance to the airfield.

Both units would participate in a number of major, high prestige operations, providing radio jamming and window curtains for the bomber formations. ‘Spoof’ operations were common, diverting enemy fighters away from the real force and playing a daring game of cat and mouse with the German radio operators. As the war drew to a close, so too did the operations from 214 and 223. Eventually in July 1945 both Squadrons were disbanded, 214 being the renumbered 614 squadron, with 223 having to wait until 1959 before being reborn as a THOR missile squadron.

With the withdrawal of the heavies, the end was near for Oulton. After being used for storage of surplus Mosquitoes for a year it was closed and sold off. The end had finally arrived and Oulton closed its gates for the last time.

Oulton airfield stands as a reminder of the bravery of the light bomber and ECM crews; today many of the original buildings still remain, used for agricultural purposes and even by the National Trust.

One of the few buildings that remain, the former squadron offices.

Whilst the general layout of the airfield has changed with the addition of farm and ‘industrial’ units, its layout can still be recognised. The majority of the runways still exist, now housing poultry sheds, and large sections can easily be seen from the roadside. Luckily, even some of the original huts from the technical area are also in existence and ‘accessible’.

Approaching from the north, the first reference point is the memorial. Standing at the crossroads on the north-eastern corner, it serves as a pointer directly in line with the centreline of the Runway 2. Behind you to your right is the former sick quarters, here would have been an ambulance station, Static water tank and sick quarters, now all gone. Turning right here, keeping the airfield to your left, you pass along the northern boundary, within a short distance of what would have been the perimeter track.

The first sign is a pillbox. This was placed next to the special signals workshop which consisted of three small buildings. Now overgrown, this maybe a Vickers Machine gun Pillbox, different to ‘standard’ pill boxes as it has a concrete ‘table’ beneath the gun port designed to support the heavier gun and tripod.

Further along this road, to your right, is the first and main bomb store. A small track being the only visible reminder, the walls having been removed long ago. The large concrete ‘pan’ being the entrance, on which farm products are now stored.

The second store and USAAF quarters were further along this road, again all trace has gone and it is purely agricultural now. Retracing your steps, go back to the memorial. At the crossroads, ahead of you, was Number 1 accommodation site, now all farm buildings, but formerly the officers, sergeants quarters and airman’s barracks.

Turn right here and as you drive down Oulton Street, there are a number of original buildings back from the road in a small enclave. The National Trust own part of these and use them to restore historic textiles, one of these buildings being the squadron offices. The main entrance to the airfield is further along this road and now an insignificant farm gate, allowed to grow and fill in, the path buried beneath the grass. Beyond this, you can see some remaining buildings across the field, truly overgrown and very dilapidated, these are possibly the crew locker and drying rooms. Continue on along this narrow road and you arrive at the pond. Behind the pond, stands a well-preserved hut and smaller buildings. These were the main workshops, rubber store and general stores, now holding agricultural products and waste material. Certainly they are some of the better preserved buildings on the site. Further along, the road crosses the main runway, here it is full width on both sides of the road. Poultry sheds stand on the main section, whilst farm waste resides on the left.

The eastern end of the main runway.

Continuing on and the road crosses the third runway, where we turn left. We can now see the site of one of the four T2s, the road at this point using the original perimeter track before it departs away to the north.

From here, we return north, head back past the airfield and return to the main road. Here we turn right and follow the road for a few miles east through the woodland where we arrive at Blickling Hall. The accommodation sites here, include the No.1 and 2 WAAF sites, NAAFI, No. 4 and 5 accommodation site and various service sites.

The east wing of the Blickling Hall is now a museum, formerly the barracks and still shows the original paintwork. A range of uniforms, photos and personal stories can be seen and read.

There are virtually no remnants of the other sites which were primarily Nissen huts. Footpaths do allow you to walk through these, now natural spaces, walking in the footsteps of former airmen and women.

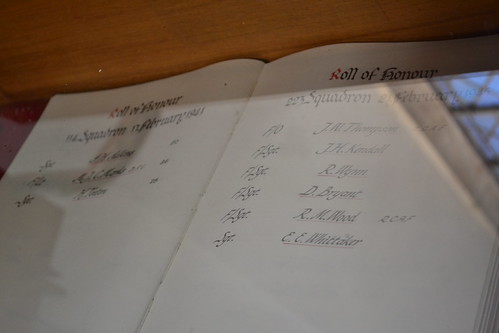

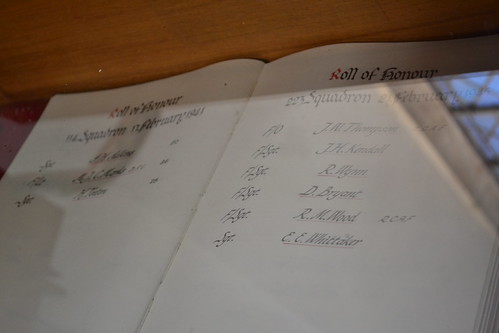

Next to the Hall, is the church of St. Andrew, in here is a small collection of artefacts and a roll of honour for those who died at Oulton. Also here is the sole grave of Sergeant L. Billington, who died on March 4th 1945 at the young age of 20. He was part of a crew in a Fortress III (B-17) on window duties. As the aircraft was returning from its mission, it was attacked by a JU 88, causing it to crash on the airfield boundary. All but two of the crew were killed*3, their bodies being buried in different locations. A sad end to another young life at Oulton.

The Roll of Honour at St. Andrew’s Church, next to Blickling Hall.

RAF Oulton housed a range of aircraft types and nationalities. Their role encompassed many important duties and missions that certainly helped defeat the Nazi tyranny. Many of these young men, led the way in today’s electronic counter measures and electronic warfare. The daring missions they led, firmly embedded in our history, and now the remnants of Oulton stand as a reminder to both their sacrifice and dedication.

Notes and Further Reading.

*1 The ground crew were:

E.J. Bone, Aircraftsman Ist Class

H. Bramham, Aircraftsman 2nd Class

A.C. Emery, Aircraftsman 2nd Class

K.F. Fowler, Aircraftsman, 2nd Class

F. Packard, Leading Aircraftsman

A. Torrence, Leading Aircraftsman

Source Aircrew remembered website.

*2 National Archives, RAF Bomber command diary 1940.

*3 The crew were:

P/O H Bennett

Sgt. L Billington

F/S H. Barnfield

W/O LJ Odgers (RAAF)

F/S W Bridden

F/S LA Hadder

F/S F Hares

Sgt. A McDirmid (injured)

W/O RW Church (injured)

Sgt. PJ Healy

Source: Chorley, W.R., RAF Bomber Command Losses 1945, 1998, Midland Counties.