If you follow the A151 towards the main A1, close to the Lincolnshire / Leicestershire border, and you come across Twyford Woods, and an airfield that is little known about, yet its part in history is perhaps one of the most important played by any airfield in Britain. Famous battles such as the Normandy invasion, the Ardennes and the crossing of the Rhine all took place because of the events that occurred here, and were it not for this airfield, many may not have been as successful as they were. In Trail 3, we head further west to perhaps one of Britain’s best kept secrets – RAF North Witham.

RAF North Witham (Station 479)

RAF North Witham sits quietly amongst the trees of Twyford Woods, a site originally known as Witham Wood, which is now a public space owned and maintained by the U.K.’s Forestry Commission.

Originally, North Witham was one of twelve airfields in the Leicestershire cluster intended to be an RAF bomber station for No. 7 Group, however, it was never used operationally by the Royal Air Force, instead like ten others in the area, it was handed over to the US Ninth Air Force and in particular the IX Troop Carrier Command.

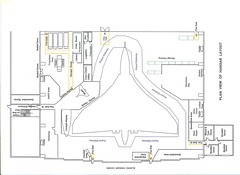

As it was originally designed as a bomber station it was built to the Air Ministry’s class ‘A’ specification, formed around the usual three triangular runways, perimeter track and aircraft hardstands. With construction beginning in the mid-war years 1942/43, its main runway would be 2000 yds long, with the second and third runways 1,400 yds in length and all 50 yds wide. To accommodate the aircraft, 50 ‘spectacle’ style dispersals were built, scattered around the adjoining perimeter track. As a bomber base it had a bomb store, located to the north-eastern side of the airfield, with the admin and technical site to the south-east. The usual range of stores and ancillary buildings adorned these areas. One architectural feature of North Witham was its operations block, built to drawing 4891/42, it was larger than most, with ceilings of 14 feet high. Amongst the myriad of rooms were a battery room, cipher office, meteorology room, PBX, traffic office and teleprinter room, all accessed through specially designed air locks. A further feature of this design was the attachment of a Nissen hut to house plant and boiler equipment, a feature not commonly seen at this time.

Aircraft maintenance could be carried out in one of two ‘T2’ hangars with additional work space provided by one of six ‘Butler’ hangars. Designed and built by the Butler Manufacturing Company of Kansas, USA, these were supplied in kit form and had to be erected on site by an Engineer Aviation Battalion. These hangars consisted of rigid box section girders over a canvas cladding, and once fully erected, gave a wide 40 ft span. Quite a rare feature, these types of structures were only built in limited numbers during the Second World War and only appeared on American occupied airfields. Post-war however, they were far more commonly used appearing on many American cold-war sites across the UK.

A ‘Butler’ hangar under construction by members of the 833rd Engineer Aviation Battalion (EAB) at a very snowy North Witham (@IWM479)

The Ninth Air Force was born in 1942 out of the ashes of the V Air Support Command, and then combined with units already located in the England operating under the American Eighth Air Force. Its initial activities focused on the allied push across North Africa followed by the move up into southern Europe through Italy.

Moving to England in October 1943, it then became the tactical Air Force that would support the Normandy invasion, supplying medium bombers, operating as troop support and finally providing supply flights. Facilitation of this massive invasion required both a huge backup, and an intricate supply and support network. North Witham would form part of this support network through both repair and maintenance of the troop carrier aircraft that were operated by the Ninth Air Force – primarily the C-47s. The main group undertaking this role at North Witham was the 1st Tactical Air Depot comprising the 29th and 33rd Air Depot Groups between January and September 1944*1. One of a number of depots, they were once described as the “backbone of Supply for the Army Air Force”, and had a complicated arrangement that encompassed numerous groups across the entire world theatre.

For such a large base, North Witham would be operationally ‘underused’, the only unit to fly from here being those of the IX Troop Carrier Command (TCC), who would primarily use C-47 ‘Skytrains’ – an established and true workhorse, and one that would go on to supply many air forces around the world.

During the Sicily campaign, it was found that many incoming aircraft were not finding the drop zones as accurately as they should, and as a result, paratroops were being widely and thinly scattered. More accurate flying aided by precise target marking was therefore required, and so the first Pathfinder School was set up.

The IX TCC Pathfinder School (incorporating the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Pathfinder Squadrons) was formed whilst the TCC was at RAF Cottesmore in Rutland. Initially having only seven C-47 aircraft, it arrived at North Witham on March 22nd 1944. These aircraft were fitted with, at the time, modern Gee radar and navigation equipment, along with SCR-717 navigational radar housed in a dome beneath the fuselage of the aircraft. This combination of equipment would allow the aircraft to be used as ‘Pathfinders’, and would be used to train both crews and paratroops of the 101st and 82nd Airborne to mark targets prior to the main invasion force arriving.

These crack troops would train at North Witham before returning to their own designated bases to pass on their newly acquired skills. The idea being that these troops would set up ‘homing’ stations using ‘Eureka’ beacons that would connect to ‘Rebecca’ receivers in the aircraft (distinguished from the outside by antenna protruding from the nose). This would allow flying to near pinpoint accuracy even in poor weather or at night; something that would be employed with relative success in the forthcoming Normandy landings.

On arrival at North Witham, the Pathfinders were accommodated in the huts originally provided for the depot’s crews – some 1,250 enlisted men and 75 officers. Many of these displaced men were rehoused in tents along the northern end of the site which only added a further strain to the already rudimentary accommodation that was already in place at the airfield. At its height, North Witham would house upward of 3,700 men in total, a figure that included an RAF detachment of 86 men and large quantities of GIs.

After arrival, the crews began training for the invasion. Flying cross country flights enabled them to practise using their new radar sets, flying in all weathers, at night and during the day. By D-Day, all navigators had been using the equipment in excess of 25 hours and were considered more than competent in its operation.

With postponements of the invasion came frustration, crews and paratroops mentally prepared for war were let down, there was little for them to do to release the tension that many must have felt.

On June 5th, after the plan was finally given the go ahead, some 821 Dakotas at various sites across England were primed ready for the initial wave of the invasion. Timing was of the utmost importance. As rehearsals had shown, seconds could mean the difference between life and death – for the crews of the C-47s, the pressure was on.

Around 200 Pathfinders of North Witham were the first to leave the UK and enter the Normandy arena. Departing late in the evening of June 5th, men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne climbed aboard their twenty C-47s and rose into the night sky. North Witham based C-47A*2 ‘#42-93098’ piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch*3, led the way. Nineteen other North Witham aircraft joined Crouch that night, and remarkably only one aircraft was lost in the entire flight. Flying under mission ‘Albany‘, the Douglas built C-47A-15-DK Skytrain, #42-92845 (aircraft #4) was lost en route either due to mechanical failure, or as some sources say, following a direct hit by Anti-Aircraft fire. Either way, the aircraft lost an engine and was forced to ditch in the sea. Once down, the crew and paratroops on-board were rescued by the British destroyer HMS Tartar.

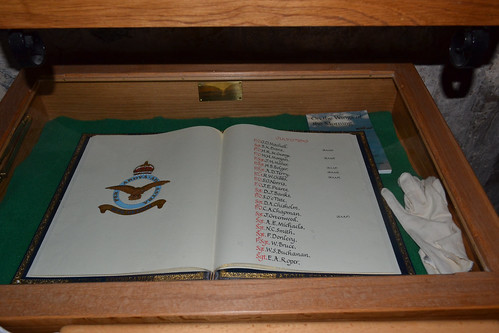

The Crew of C-47A #42-93098, a few hours before they left for Normandy. Including Pilot, Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch (centre), Captain Vito Pedone (copilot), Captain William Culp (Navigator), Harold Coonrod (Radio Operator), along with Dr. Ed Cannon (physician), and E. Larendeal (crew chief)*1

The aircraft flew in groups of three in an in-line ‘V’ formation; aircraft 1, 2, 3 followed by 4, 5, 6; 19 and 20 (added as a late decision); 7, 8, 9; 10, 11, 12; then 16, 17 and 18. The formation was finally completed with aircraft 13, 14 and 15 bringing up the rear. Each C-47 would deposit its collection of Paratroops over six drop zones (DZ) A, C, D, O, N and T between 00:20 and 02:02.

Flying alongside aircraft #19, the only pair on the flight, was C-47 #20 piloted by 1st Lt. Paul F. G. Egan, of Massachusetts. Joining him in the aircraft were: Sgt. Jack Buchannon, Crew Chief (Mass); 2nd Lt. Richard A. Young, Co-Pilot (Ohio); 2nd Lt. Fern D. Murphy, Navigator (PA); Staff Sgt. Marvin Rosenblatt, Radio Operator (NY) along with ten Combat Engineers of the 101st Airborne who were dropped at Sainte-Mère-Église on the Cherbourg Peninsula early in the morning 6 June 1944.

Lt. Paul Egan had a remarkable service history, serving in each of the US Army, US Army Air Force and US Air Force after the war, a service that stretched from 1939 to 1967. His remarkable record includes: Pearl Harbour in 1939 and the Japanese attack in December 1941, the Battle of Midway in 1942, followed by advanced training in 1943. This training kept Lt. Egan in military intelligence as a Pathfinder pilot flying mostly C-47s out of both North Witham and later Chalgrove. As well as dropping the paratroopers on D-Day in Operation Market Garden, he also dropped troops in Operation Varsity along with every other major airborne operation flown from England. He also flew bombing missions in B-17s and flew ‘secret’ missions in early 1945. At the signing of the Japanese surrender onboard the USS Missouri on September 2nd 1945, he was the only USAAF representative there, General McArthur wanting someone who was present at Pearl Harbour to also be present at the surrender. His record is certainly remarkable and one to admire.*5

Photo taken at North Witham Air Base, England on June 5, 1944, the night before D-Day. C-47 #20 (note the number chalked in front of the door to ensure paratroops boarded the right aircraft, and the crudely painted invasion stripes) one of the first 20 aircraft to fly with the elite group, the Pathfinders. Front row: Sgt. Jack Buchannon, Crew Chief; 2nd Lt. Richard A Young, Co-Pilot; 2nd Lt. Fern D. Murphy, Navigator; 1st Lt. Paul F. G. Egan, Pilot (Captain); Staff Sgt. Marvin Rosenblatt, Radio Operator along with ten 101st Airborne Combat Engineers dropped on the Cherbourg Peninsula early morning 6 June 1944, “D-Day” (Photo courtesy Jean Egan).

Pathfinder training continued at North Witham beyond D-Day, well into 1944. The scope of those trained expanding to include Polish paratroops of the 1st Independent Polish Airborne Brigade, who would perform a similar role to their American counterparts. These various Pathfinder groups would go on to have long and distinguished careers, supporting the battles at Arnhem, the Ardennes and also Operation Varsity – the Allied crossing of the Rhine.

As the Allies pushed further into enemy territory, the flying distance from England became too great and so new airfields were either hastily constructed on the continent or captured airfields refurbished. As a result, the Pathfinder School soon moved away to Hampshire and the maintenance units, needed nearer the front lines, gradually departed to these newly acquired bases on the continent.

September 1944 would see big changes in the Ninth and the knock-on was felt at North Witham. Firstly, the IX TCC transferred from the Ninth AF to the First Allied Airborne Army, and as a result, the Air Depot title was changed to IX Troop Carrier Service Wing (Provisional), which was re-assigned to aid and supply the new Troop Carrier Groups (TCG) now based in France. To accomplish this new role, groups often used borrowed or war-weary C-47s, C-46 (Commandos) or C-109s (converted B-24 Liberators) to fulfil their role. Secondly, the Pathfinder School was re-designated IX Troop Carrier Pathfinder Group (Provisional) and they moved away from North Witham to their new base at Chalgrove near Oxford. Now much quieter, life otherwise continued on at North Witham, but it wouldn’t long before the demand for UK-based maintenance and repair work would slow, and within months North Witham’s fate would be finally sealed.

As the end of the war approached, the airfield quickly became obsolete, and the long wind-down to closure, that many of these unique places suffered, began to take effect.

By the time the war was over, the last American personnel had pulled out and the site was handed back to the RAF’s 40 Group who, after using it for a brief spell as a maintenance depot themselves, placed it under care and maintenance. It was used as a munitions and hardware store until 1948, and then finally, in 1956, it was closed by the Ministry and within two years the site was sold off.

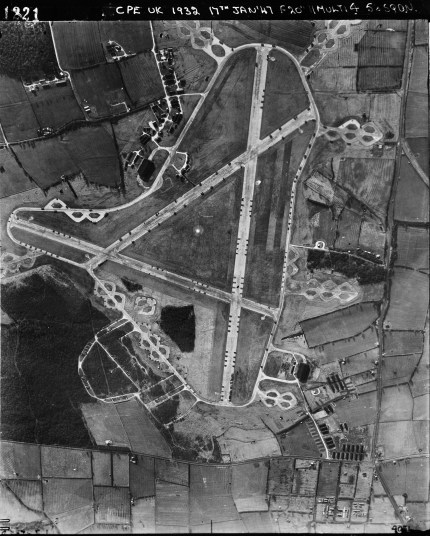

Photograph of North Witham taken on 17th January 1947. The technical site and barrack sites are at the top left, the bomb dump is bottom left. (IWM RAF_CPE_UK_1932_FP_1221)

The site, intact as it was, was returned to the Forestry Commission who planted a range of new tress around the site, covering the vast areas of grass. The technical area was developed into a small industrial unit and perhaps most sadly the watch office left to decay and fall apart.

Today the three runways and perimeter track still exist almost in their entirety, and remarkably, in generally good condition. Largely overgrown with weeds and small trees, the remainder is well hidden obscuring what little there is in the way of buildings – most being demolished and the remains left piled up where they stood. However, a T2 hangar is now used on the industrial estate and the watch office still stands tucked away amongst the trees and undergrowth. This area is a favourite place for dog walkers, and because of its runways, it is accessible for prams and pushchairs. Whilst here, I spoke to quite a few people, remarkably none of them knew of the site’s historical significance let alone the office’s existence!

Today the watch office remains open to the elements. Surrounded by used tyres and in constant threat of the impending industrial complex over the fence, its future is uncertain. Access stairs have been removed, but an entrance has been made by piling tyres up to the door – presumably by those wishing to enter and ‘explore’ further. Little evidence of its history can be seen from the outside, even the rendering has been removed, and so, any possible personal links with the past are more than likely now gone.

Returning back to the main public entrance along the perimeter track, a number of dispersal pens can be found; overgrown but relatively intact, they are a further sign that even here, war was never very far away.

North Witham was one of those ‘backroom boys’ whose contribution, whilst extremely important, is little known about. The work carried out here not only helped to maintain a strong and reliable fighting force, but one that spearheaded the frontal invasion of Normandy. It served as a cold and perhaps uncomfortable home to many brave troops, many of whom took the fight direct to Nazi Germany.

Standing here today, it is quiet and strangely surreal – you can almost hear the roar of engines. Looking along its enormous runways you get an eerie feeling – how many troops also stood here, spending their last few hours in this quiet place. Looking around now, it is difficult to imagine the immense work that went on here, the gathering of equipment as preparations were made for the big push into Normandy on that famous June night.

North Witham is truly a remarkable place, hidden away amongst the trees as a giant time capsule, a monument to those who lived, worked and died during that turbulent time in 1944-45.

Sadly in May 2015, Twyford Woods was the scene of a large illegal rave, over 1000 people attended the event where a number of arrests were made in the violent altercations that took place*4. A sad day that would turn the souls of those who sacrificed themselves for the freedom we take for granted so very easily today.

(North Witham was originally visited in early 2013)

Links and sources (RAF North Witham)

*1 American Air Museum in Britain

*2 C-47A #42-93098 itself was later lost whilst flying with the 439th Troop Carrier Group (TCG) on September 18th 1944, whilst flying in support of Operation ‘Market Garden‘ in Holland.

*3 Superb footage of Crouch and his crew as they depart from North Witham is available on-line, it also shows the Watch Tower in its former glory.

*4 A report of the event is available on the BBC News website.

*5 My sincere thanks go to Jean Egan, daughter of Lt. Paul Egan, for the information and photograph.

An excellent website contain photos of paratroops and air crew as they prepare for embarkation and advance through France.