In Trail 11, we visit three airfields all within a stones throw of each other, and all situated around Britain’s third smallest city Ely, in Cambridgeshire. They were all once major airfields belonging to the RAF’s Bomber Command. Post war, two of the three went on to be major Cold War stations, one housing the Thor Missile, whilst the second housed the fast jets of the RAF’s front line of defence. It is this one we visit in the final part of this Trail. It is also one whose days are numbered, already closed and earmarked for development, the bulldozers are knocking at the door whilst the final plans are agreed and development can begin. But this development may not be the total clearing of the site it often is. With plans to integrate parts of this historical site into the development, it is aimed to create a living and working space that reflects it significant historical value. Today, in the final part of Trail 11, we visit the former station RAF Waterbeach.

RAF Waterbeach.

The land on which Waterbeach airfield stands has a history of its own, with royal connections going back as far as the 12th Century. Eventually divided up into farms, one of which, Winfold Farm, stood at the centre, the area would be developed into a long-term military base.

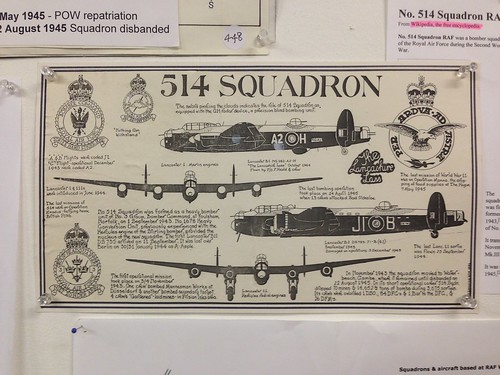

RAF Waterbeach would have a long career, one that extended well into the Cold War and beyond. It would be home to no less than twenty-two operational front line squadrons from both Bomber Command and Fighter Command, along with a further five Conversion Units. With only six of these units (3 front line and 3 Conversion Units) operating during the Second World War, the majority would be post-war squadrons, three being reformed here and eleven being disbanded here. This range of squadrons would bring with them a wide range of aircraft from Dakotas and Wellingtons through the four engined heavies the Stirling, Lancaster and B-24 Liberator, and onto the single and two seat jets, the Meteor, Hunter and Javelin, who would all grace the skies over this once famous airfield.

Originally identified as a possible site in the late 1930s, the land was purchased by the Government with development beginning in 1939. The farm at its centre was demolished and the surrounding fields dug up and prepared for the forthcoming heavy bombers of Bomber Command. As with many airfield developments, there was local opposition to the idea, partly as it occupied valuable Fen farmland with a farm at its centre.

In the early years of the war, it was found that heavy aircraft, bombers in particular, were struggling to use the grassed surfaces originally constructed on pre-war airfields. The rather ridiculous test of taxing a laden Whitley bomber across the site to test the ground’s strength would soon be obsolete, and so after much internal wrangling, hard runways were eventually agreed upon which would be built into all bomber and some fighter stations from that point forward*1.

As an airfield built at the end of the expansion period and into the beginning of the war, Waterbeach would be one of those stations whose runways were hard from the start; a concrete base covered with tarmac to the soon to be standard 2,000 and 1,400 yards in length. By the end of 1945, there would be 35 heavy bomber hardstands of the ‘frying pan’ style and a further three of the spectacle style, all supporting a wide range of aircraft types well into the cold war.

Waterbeach would develop into a major airfield, capable of housing in excess of 3,000 personnel of mixed rank and gender, dispersed as was now common, over seven sites to the south-eastern corner of the airfield. The bomb store was located well away to the north of the airfield, but surprisingly close to the main public road that passed alongside the western boundary of the site.

Being a bomber base, there would be a wide range of ancillary and support buildings, including initially, two J type hangars, followed by three T2s and a B1. The site was considered by its new occupants as ‘luxurious’ and compared to many other similar airfields of that time, it certainly was. This opinion was not formed however, when it opened on January 1st 1941, as it was in a state that was nowhere near completion. The official records show that along with Group Captain S. Park (Station Commander) were the Sqn. Ldr. for Admin (Sqn. Ldr. F Carpenter), Station Adjutant (Flt. Lt. H. Daves) and Sqn. Ldr. J. Kains (Senior Medical Officer) who were joined by various other administrative officers, Senior NCOs and 157 corporals and Airmen. They found the majority of buildings incomplete, the runways and dispersals still being built and the site generally very muddy. The cook house was ‘adequate’ for the needs of the few who were there, but the sergeants mess could not be occupied for at least another five to six weeks.

As occurred with many airfields at this time, the first personnel to arrive took up the task of completing many aspects of the outstanding work themselves, laying concrete, installing fixings and preparing accommodation blocks for the forthcoming arrivals.

During these early years of the Second World War, the Luftwaffe targeted Britain’s Fighter airfields as a way of smashing the RAF before the German planned invasion could take place. Whilst this policy failed, attacks on RAF airfields were continued, becoming more ‘nuisance’ attacks or small raids, in which airfields beyond the reaches of Kent and London were also targeted. Waterbeach itself was subjected to these nuisance attacks on two occasions between the New Year December 1940 and February 1941. During these, some minor damage was done to the site (hangars, aprons and a runway) and there was one fatality.

These early days of 1941 would be a busy time for the personnel at Waterbeach, further attacks intermixed with flying activities kept them alert and on their feet. Being a large base, its runways would become safe havens for crippled or lost aircraft desperately trying to find a suitable site on which to put down. A number of aircraft used Waterbeach for such an activity, primarily Whitleys and Wellingtons, many being damaged and unable to reach their home bases further north in Yorkshire.

With changes in airfield command taking place a month after its opening, the first units to arrive were the Wellingtons of No. 99 Squadron RAF, in a move that was delayed by a further month in part due to the late completion of the construction work and also because of yet another nuisance attack by the Luftwaffe.

Whilst 99 Sqn were preparing to transfer to Waterbeach, operations would continue from their base at Newmarket Heath, bombing raids that took the Wellingtons to Breman, Gelsenkirchen, Dusseldorf, Duisburg and Cologne.

Once arriving here at Waterbeach, they found early missions, on both the 1st and 2nd of April 1941, being cancelled due to poor weather – training would therefore be the order of the day. The 3rd however, would be very different. With revised orders coming through in the morning, thirteen aircraft would be required to attack the Battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau located in Brest harbour.

Whilst one of the aircraft allocated was forced to land at RAF St Eval in Cornwall due to icing, the remainder flew on completing the raid which was considered a “great success”. One crew, led by P/O. Dixon, carried out particularly daring diving attacks scoring direct hits on one of the two ships in question. Whilst no other hits were recorded by the Wellingtons, many bombs fell very close to the targets and it was thought some may have even struck one of the two ships.

With the squadron being stood down on the 5th April, there would be a return to flying on the 6th, with ten aircraft being allocated to a maximum effort mission returning to Brest and the two German ships. Taking off at 20:17, ten aircraft flew directly to the harbour and carried out their attacks, whilst a ‘freshman’ crew flew a diversionary mission elsewhere. Although all but one aircraft returned safely to base, one aircraft did have problems when its 4,000lb bomb fell off the mounts prematurely.

Flying the MK.I, MK.IC and MK.II Wellington, 99 Sqn would carry out further operations to Germany, and on one of these sorties on the night of April 9th/10th, eight aircraft were assigned to Berlin, two to Breman and a further two to Emden. One Wellington, R1440, piloted by P/O. Thomas Fairhurst (s/n 85673) crashed in the Ijsselmer near Vegesack, whilst the second, R3199 disappeared without trace after making a distress call. On the 30th, the Air Ministry informed Waterbeach that POW cards had been received from a German prison camp from four of the crew: S/L. D. Torrens, P/O. P. Goodwin, Sgt. A. Smith and Sgt. E. Berry. The remaining two crewmen were also taken prisoner but this was not confirmed until much later.

April was a difficult month for 99 Sqn, operations called for in the morning were often cancelled by the evening, those that went ahead were made more difficult by poor weather over the target area. Two positive events occurring during April did bring good news to the crews however. On the 15th, the King approved an award of the DFC to P/O. Michael Dixon (s/n: 86390) for his action in attacking the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau earlier on, and on the 22nd, the Inspector General of the RAF Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt visited the station where he inspected various sections of the squadron, met the crews and discussed some of their recent operations with them. A nice end to what had been a difficult start at Waterbeach.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Bomber Command, sitting in his office at Headquarters Bomber Command, High Wycombe. © IWM (C 1013)

Throughout the summer months 99 Sqn would continue operations into Germany along with further attacks on the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau docked at Brest. With further loses on May 5/6, May 8/9, June 11/12 , and June 21st with the loss of X9643 two miles from the airfield, losses would be relatively low. In a freak accident X9643 would be lost with all of her crew when the dingy became dislodged and fouled the elevators causing the aircraft to crash and burst in to flames.

The latter months of 1941 would see two conversion flights formed at Waterbeach. Designed to train crews on the new four engined bombers, the Stirling and latterly the Lancaster, 26 Conversion Flight was formed out of ‘C’ flight of 7 Sqn on 5th October with 106 Conversion Flight joining them in December. Both units flew the Stirling bomber and were amalgamated in January 1942 to form 1651 Conversion Unit (CU) (later 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU)). Flying a mix of Stirlings and later Lancasters, they also used a Beaufighter, Spitfire, Tiger Moth and Airspeed Oxford. 1651 CU were one of only three Conversion Units set up in early 1942, with 1651 being the only Stirling unit at this point; the other two units flying with the Halifax or Liberator aircraft.

By the end of 1941, 99 Sqn would suffer thirty-four aircraft lost (2 in non-operational accidents), with many of the crewmen being killed. Whilst these were tragic losses, they were nevertheless ‘in line’ with the majority of all 3 Group operational units of that year. In early 1942 the squadron was sent overseas to India, a move that coincided with the new arrivals at RAF Waterbeach of No. 215 Sqn.

215 Sqn were going through a process of reorganisation and transfer. On 21st February 1942, the air echelon formed at Waterbeach whilst the ground echelons were already on route to India from Stradishall. With more Wellington ICs, they would also depart for India a month later, where they would stay for the remainder of the war. Being only a brief stay, their departure left Waterbeach with only 1651 Conversion Unit and its associated units in situ.

Being a conversion unit, 1651’s aircraft were worn and often unserviceable, and in February 1942, they could only muster five flight worthy aircraft. As the need for more bomber crews grew, so too did the number of aircraft supplied to the Conversion Units, and as a result the number of crews undertaking training also grew. To help meet this demand, another new squadron was formed within 1651 CU in the April, that of 214 Squadron Conversion Flight. Another Flight was also formed at Alconbury and moved to join these two units, No. 15 Squadron Conversion Flight. The idea behind this unit was to provide aircrews with operational experience, an experience many would find hard to deal with.

In Part 2 we see how the Conversion Units were sent into battle, how they coped with the rigours of the aerial war over occupied Europe and then the change from Stirlings to the Lancaster.