Part 2 gave us an insight into Thurleigh’s transformation as a USAAF base bringing the American 306th Bomb Group, whose early months were marked by harsh conditions, inexperience, and heavy losses. Yet through resilience and innovation, they adapted quickly. With these lessons learned, the Group now faced the escalating intensity of 1943’s air battles over occupied Europe.

Under Siege: New Tactics, Devastation in December and Heroic Returns

Not only were the Luftwaffe now changing tactics by attacking head on, but they were also developing other methods and weapons to down these heavy bombers.

By attacking in rotation, one group being replaced by another as they refuelled and rearmed, the Luftwaffe fighters were able to keep up an almost endless attack on the formation; fresh eyes and ammunition gradually sapping the gunner’s energy.

This was one such tactic used on the 20th December 1942. After the escort of Spitfires had left and the bomber formation approached the target, they were attacked by a new group of fifty or so FW-190s. The 306th took the full force of the attack losing four aircraft with another two crash landing in England. A further twenty-nine were badly damaged, some even written off. The vulnerability of the unescorted heavy bomber had become all too apparent.

In November and December, the 306th Bomb Group continued operations against targets in France with mixed success, hampered at times by poor weather, mechanical issues, and crew illnesses. On 7th December, many aircraft returned without releasing their bombs due to heavy cloud cover, and the following day a mission over Lille saw Captain Adam’s aircraft shot down and another bomber badly damaged, with several crews breaking protocol to protect it until all returned safely. During November alone, the group was recognised with twenty-six Air Medals, a Distinguished Flying Cross for Colonel Overcracker, and two Purple Hearts for wounded airmen.

A New Chapter; Thurleigh Faces Tough Reforms

December 9th 1942 bore witness to a remarkable event in history when Thurleigh airfield was officially handed over from RAF control to the USAAF, the first such event to have taken place. The change in ownership didn’t however, immediately affect operations and the closing month of the year saw further flights into enemy territory with yet more losses. These increase in losses were met with a corresponding decline in morale.

But as Christmas approached, there was a change in sentiment with a festive Christmas diner and New Year celebrations in which a newly formed band played music well into the night. The end of the year went out with many regrets but brought high hopes for a much better and happier 1943.

The dawning of the new year then saw big changes occur at Thurleigh. In command of the Eighth Air Force was General Spaatz, who at the time was meeting with with General Eisenhower to discuss the future of the North African Air Force, leaving Ira Eaker in charge of the Eighth Air Force in Britain. His own replacement, Brigadier General Newton Longfellow, was charged with reviewing the losses being incurred by the air force, and found at Thurleigh, a lack of discipline and poor leadership.

Even though Col. Overcracker, the Commander in charge at Thurleigh, was a well liked commander by his men, there were concerns from those above that he was overly caring for his crews to the point that they were able to ‘get around’ him far too easily. This, Newton thought, was the reason why so many aircraft and crews from the Group had been lost in those early months of their war.

Newton consulted with Eaker who called upon Col. Frank Armstrong, one of the six original staff members at the inception of the 8th AF, to go to Thurleigh and make amends. This he did. he ruled the men with a tight and hard discipline turning the Bomb Group’s fortunes around, a move that was later recalled in the novel and film “Twelve o’clock High” written by one of Eaker’s other original six staff members, Cap. Beirne Lay Jr. along with Maj. Sy Bartlett one of Spaatz’s staff officers.

Armstrong would take over the 306th for a month and a half. Being assigned to the Group on 2nd January 1943. During that time, he would make dramatic changes to both the structure and the outcomes of the Group.

Baptism by Fire: Losses Continue Despite Command Changes

But change came slowly. Even as Armstrong took over, the 306th continued to lose aircraft and crews. On January 3rd, seventy-two B-17s and thirteen B-24s from the 44th, 91st, 303rd, 305th and 306th Bomb Groups were sent back to bomb the U-boat pens at St. Nazaire. After all seven of the 306th aircraft bombed the target they headed for home. The Journey in however, had been hell for the crews as flak had been both heavy, thick and accurate, with many aircraft from all groups sustaining damage.

One 306th aircraft, B-17F – #41-24470, “Sons Of Fury” had been so badly damaged that two engines were out of action and the nose with both the navigator and bombardier inside, was blown off. Separated from the rest of the formation, it was soon picked up over the sea by FW-190s and attacked yet again. Slowly losing height, it would eventually ditch in the cold waters of the Bay of Biscay. But even as it did so, the top turret continued to fire at the passing 190s, who continued to strafe the aircraft and crewmen who were now in the water, even though it was down and sinking. The heroic actions of the gunner in the turret, T/Sgt. Arizona Harris, were witnessed by a tail gunner in another 306th aircraft, who described how Harris continued to fire his weapons even as the water filled his turret until eventually, the firing stopped. His actions that day led to him receiving a DSC posthumously.

From page 50 of the wartime British Edition of “Target Germany” – 1944. The text relates what a 369th BS officer witnessed on the 3 January 1943 mission to Saint-Nazaire, when B-17 # 41-24470 went down. (IWM UPL 44487)

Meanwhile at Thurleigh, the first of Armstrong’s many changes were implemented starting with Colonel Overcracker, who on the 4th, was relieved from the organisation and posted to Headquarters. Three days later Major Coleman was relieved from his duties as Group Adjutant and reappointed as Group Executive Officer, his vacant position position being taken over by Captain Charles Day Jr.

To bolster the falling crew numbers, new crews were brought in, all arriving between the 14th and the 16th January, a move that coincided with seventeen aircraft attacking the locomotive and engineering works at Lille. Led by Major Wilson, the successful attack was marred by the tragic collision between #41-24471 “Four of a Kind” piloted by 1st Lt. Frank Jacknick and another B-17 #41-24498 piloted by 2nd Lt. Wallace Kirkpatrick, both of the 369th BS. *10, There were few survivors from the crash and those that did were taken prisoner by the Germans.

A report by a following crew*11 highlighted how Kirkpatrick’s aircraft was thought to have lost sight of the lead plane as they turned into the sun. The lead plane being unaware, carried on in a straight line. Kirkpatrick’s aircraft then crossed the lead plane at about 30o catching the tail fin with his propellers. The lead ship looped as a result breaking in half as the propellers from the second ship tore through its fuselage sending the aircraft toward the ground, such were the perils of formation flying in a war zone.

Concrete Cracks and Operational Strains

The continued onslaught against Germany led to further issues at Thurleigh airfield. A common problem on some airfields was that the weight of the heavy bombers was too much for the thin concrete tracks, and soon the substrate of both the perimeters and the runways began to fall apart. At Thurleigh, this caused numerous difficulties whilst taxiing and taking off, with tyres being repeatedly blown or damaged. The problem became so severe that engineers had to be brought in quickly and essential repairs made. *12*13

The swiftness of the early changes made by General Armstrong continued on with postings and further changes of role. On the 18th January, Major Putnam was assigned as the 306th Group Operations Officer, followed by on the next day, Major Landford who was relieved of command of the 368th and reassigned to the 11th CCRC. His departure was met with sadness from the crews as he had led them from the start and was liked by the crews. The 20th then saw Capt. Mack Mckay reassigned from the 423rd to the 368th; he would be promoted to Major at the end of February only to be relieved from his assignment and duty in early April.

A Turning Point: The 306th Strikes Back

The 23rd January was then marked by two major events. Firstly, Lt. Col. Delmer Wilson was released from his post and reassigned to the 1st Combat Wing, and secondly, seventeen aircraft of the 423rd took off on a return visit to the U-Boat base at St. Lorient – an operation that had previously caused huge problems for the Group. Led by Major Wilson of the 423rd, the attack was, this time, successful and there were no loss of aircraft, even the bombing which devastated the German barracks, was accurate.

After almost four months of operations, the icing was finally put on the cake for the 306th when the Eighth Air Force made its first venture into Germany, and Wilhelmshaven. On 27th January, 1943, Colonel Armstrong (who had led the Eighth’s first mission with pilot Major Paul Tibbets of ‘Enola Gay’ fame) and Major Putnam, led the 306th’s formation in a 367th BS aircraft. Following along in the formation were three other B-17 Groups and two B-24 Groups, it was a mighty armada heading into German airspace. General Eaker had decided that Armstrong, and the newly reformed 306th, deserved the honour of being ‘first over Germany’ after their incredible turn round in operational achievements.

Bombing through breaks in the cloud, the formation experienced only moderate flak and few enemy fighters, the Germans being caught ‘off guard’ for once. Once again, all the 306th aircraft returned home safely, greeted by a “crowd of beaming Generals and inquisitive reporters“. Of the ninety-one aircraft dispatched in total, only three were lost, none from the 306th. To top it all, at the end of that month the 306th were further rewarded with General Armstrong receiving an Air Medal, twelve crewmen receiving Purple Hearts, and a number of others receiving other awards including three Oak Leaf Clusters.

Armstrong’s strong leadership was now paying off and results were being seen from the Thurleigh group. A bad start had led to an almost perfect six mission period for the 369th BS, with no aircraft or crewman being listed as ‘missing in action’. A remarkable record considering how fierce the spring of 1943 had been.

Leadership Legacy: Armstrong’s Departure and Recognition at Vegesack

In February, Colonel Armstrong Jr. was promoted to Brigadier General, his reign at Thurleigh then came to and end – a month and a half after he had arrived. His place as Commanding Officer was then filled by the also recently promoted, Lt. Colonel Putnam.

One issue that had come to the front during this short period, was the lack of electrically heated suits for the gunners who were now suffering from serious bouts of frostbite. A shortage of navigators and bombardiers due to illness or injury was also now starting to cause problems, and requests were put in for more of each to cover those incapacitated through various health issues.

Despite this, bombing accuracy was much improved. Mechanical issues were far less frequent and more aircraft were reaching their targets than before. In mid March this improvement was recognised following an attack on the submarine works at Veggesack, when Major Wilson led twenty aircraft of the 306th BG into both heavy and accurate flak and intense fighter opposition.

When all aircraft returned the results were commended and applauded by the Prime Minister, the Marshall of the RAF, the Secretary of State for Air, the Commanding General of the USAAF, the Chief of Air Staff RAF, and the Commander in Chief Bomber Command. In response, Major General Ira Eaker wrote “To my mind the Vegesack raid is the climax; it concludes the experiment. There should no longer be the slightest vestige of doubt that our heavy bombers, with their trained crews, can overcome any enemy opposition and destroy their targets“. *14

Two days later, Lt. General Frank Andrews accompanied several generals including Eaker on a visit to Thurleigh for an inspection of the station. A group dance was held afterwards in “B” mess which continued on well into the early hours of the next morning. The month concluded with a range of congratulatory messages of praise, it would seem the 306th were now leading the way for the Eighth Air force and their fight against Nazi Germany.

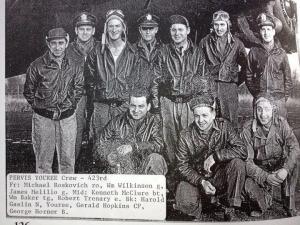

By now airmen were mounting up their operational flights, getting nearer to that magical twenty-five operations. At Thurleigh, another ‘first’ would be achieved when Technical Sgt Michael Roskovitch achieved that golden figure in April 1943.

First to Twenty-Five: Sgt Roskovitch’s Milestone

Roskovich, from Pennsylvania – known as “The Mad Russian” because of his distinctive looks and matching personality – was the son of a Russian immigrant and was posted directly to the 306th BG at Thurleigh and assigned to the 423rd BS.

He achieved his ticket home on April 5th; not only was it his first tour of duty ,but the first of any 8th Air Force airmen, a significant milestone in the organisation’s history, However, instead of going home as he was entitled to do, Roskovich opted to continue on with further operations extending his service record even further. He was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lt. as a Gunnery Officer going on to complete a further eight missions before losing his life.

On 4th February the following year (1944) he was part of a crew in B-17 #42-31715 on a training flight to RAF Drem in East Lothian, Scotland. On take off from Drem, the aircraft, with four crew and two British passengers on board, suffered an engine failure in the number 1 engine. With little time to think, the pilot opted to continue the take off on three, which proved to be a disaster as the aircraft failed to gain height and crashed into a field just beyond the airfield boundary. All those on board were killed that day including Michael Roskovich.

Technical Sgt Michael Roskovitch (sitting left) of the 423rd BS, 306th BG, who achieved 25 missions on April 5th 1943, the first American to do so. (IWM UPL 20320)

Roskovitch’s remarkable April achievement was followed up the very next day by Lt. James Pollock, also of the 423rd BS, who became the first Officer to achieve his twenty-five missions. With a third that month, the magical twenty-five was indeed achievable and many more airmen in the 306th were also closing in on that coveted title.

These three landmark achievements that April were however, to be overshadowed by what was perhaps the pinnacle of disasters for the 306th. On the 17th, no less than ten aircraft were lost on one single mission.

A Day of Tragedy: The Bremen Raid, 17 April 1943

According to the mission report*15, it was a maximum effort operation with the 306th sending out twenty-six aircraft at 09:45 to attack the Focke-Wulf plant at Bremen. The troubles started some fifty miles out when one aircraft had to return due to an oxygen failure. A second then turned back with one engine out and a further causing problems. On approach to the target the weather was clear and visibility good, allowing the 50 – 100 reported enemy fighters to clearly see the formation and pick out their targets. A mix of Me 109s and FW 190s swarmed the Americans in a determined and aggressive frontal attack, stragglers being picked off by a mix of Me 110s, Me 210s and JU 88s bearing various markings. In an attempt to split the formation, a new type of weapon was used, ‘aerial bombs’ dropped from above the formation to explode in amongst the bombers. The shrapnel from exploding bombs simply adding to the incredible amount of explosives already facing the bomber crews on their long and what must have seemed slow progress to the target.

The attacks started long before the target was reached with two aircraft from the 306th going down. Approaching the city, the bombers faced flak that was both intense and accurate, many having to perform violent evasive moves to avoid being hit. Those inside the fragile B-17s being thrown about the fuselage like rag dolls. Crews reported that the resultant smoke was so intense that they couldn’t see where they were going and had to fly using their instruments instead of visually.

Once the bomb run was completed and all bombs dropped, the attackers returned and a further six bombers were seen to go down. Another two were also lost but in the chaos and mayhem that ensued, it was difficult for crews to establish just when that was. Numerous parachutes were seen, and it was too many to suggest there weren’t high casualties.

Despite all this, bombing was reported as ‘good’ with several principle buildings being set alight. Unfortunately though, no photographs were taken as the cameras were located on those aircraft that went down; of the remining ones they simply failed to function.

Of those aircraft that did return, two were so severely damaged that repairs took a further three weeks to complete. Another three were out of action for almost a week and a sixth landed away at RAF Coltishall its damage at the time unknown. The mission had been a slaughter.

Summer Challenges: The Epic ‘La Mesa Lass’

The early summer of 1943 saw extensive use of these new weapons to break up the bomber formations. Stragglers and lone aircraft being far easier to attack and bring down that those offered the protection and security of a tight formation. Not wanting to forgo this protection, the B-17s were determined to remain together as long as they could. Rockets and aerial bombing by the Luftwaffe simply made this more challenging.

It wasn’t all one sided though. For on May 21st twenty-one aircraft were dispatched to Wilelmshaven as part of a much larger force of heavy bombers. During the attack the determination of the air-gunners paid off, with one B-17 crew, that of #42-29666 (La Mesa Lass) being credited with the shooting down of eleven enemy aircraft, a record for the European Theatre.

The journey home for Lt. Robert Smith and his crew in ‘La Mesa Lass’ was one of great courage and determination. Over the target the aircraft was hit by flak knocking out two of the four engines. From there, until they were over the sea, they were relentlessly attacked by enemy fighters, as many as five at any one time, eventually losing a third engine. Now with little power and ‘down on the deck’ with fires repeatedly starting, all guns but the top turret ran out of ammunition. Shadowed by a Ju 88 waiting for the ‘kill’ co-pilot Lt. Robert McCallum climbed into the vacated turret and took aim. Giving a long burst, he became the only co-pilot in the Eighth Air Force to shoot down an enemy fighter.

Now barely flying, ‘La Mesa Lass’ was forced to ditch in the sea. The crew’s continued determination to ‘get home’ finally came to an end, and after a controlled ditching, all the crew managed to escape and climb into the dinghies where they remained for almost thirty hours before being picked up by the Royal Navy the following day.

Farewell Flight: The Death of Captain Raymond Check

On June 26th, 1943 Captain Raymond Check departed Thurleigh in ‘Chennault’s Pappy III‘ on what should have been an easy run – a milk run – to attack the German airfield in Tricqueville, France. As a farewell, Check’s old friend and commander, Lt. James Wilson, flew as pilot and the pilot, Lt. William Cassidy flew as waist gunner. Check sat in the co-pilot’s seat, his usual position in the aircraft.

Just seconds before bomb release, a canon shell ripped through the cockpit striking Check in the neck where it exploded decapitating him. A fire started in the cabin which Wilson tried putting out with his bare hands having removed his gloves just seconds earlier. With Oxygen now pouring into the cockpit it quickly became an inferno. Wilson with little usable flesh beneath his elbow and in excruciating pain, tried to control the aircraft with what was left of his limb, all the time a further crewman tried to extinguish the fire with a small fire extinguisher. With his face and hands so badly burnt there was little skin left, Wilson fought on, when suddenly another shell struck the flares igniting them, setting off another fierce fire in the same confined space.

Cassidy, on hearing the alarm bell, made his way to the cockpit to be greeted by the most horrific sight imaginable. He tried to administer morphine to Wilson before passing him to a passenger medic on board who had joined them for ‘experience’.

Cassidy sat in the pilots seat next to the decapitated body of his co-pilot trying to avoid looking at him. With help from the navigator, Lt. Milton Blanchette – also on his 25th mission – he brought the badly damaged ship home to Thurleigh landing from the downwind direction so as to avoid Check’s waiting girlfriend and wife to be, a nurse, and the welcoming group setting up a party for Check.

In a matter of moments, what should have been a gloriously happy day turned to the most gruesome of events that would no doubt affect the lives of so many people for evermore.

Captain Raymond J. Check 423rd BS, 306th BG, killed June 26, 1943 on his 25th mission (IWM UPL 26584)

Visitors in the Wake of Tragedy; but The Cracks are Showing

The following day, a pre arranged visit occurred in which the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden; Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers (ETO Commander); Maj. Gen. Ira Eaker (USAAF Commander); Brig. Gen. Lonfellow and Brig. Gen. Armstrong were all given a tour of the airfield. Following such a dramatic event, the visit probably did little to lighten the mood at Thurleigh that particular afternoon.

Thurleigh’s transformation into a USAAF base began in 1942 bringing the 306th Bomb Group across the Atlantic, the first American unit to take the fight to occupied Europe from British soil. Their welcome was far from easy – mud, unfinished huts, and constant shortages made daily life tough, while their earliest missions were plagued by heavy losses and accidents. Captain Paul Adams’s aircraft was lost over Lille, Captain Raymond Check was brutally killed on his last mission and others returned shot full of holes. Yet through adversity, and a complete change in command, the Group hardened quickly, adapting tactics and strengthening their Flying Fortresses. By year’s end, the men of the 306th were tested, blooded, and ready for more.

The entire history can be read in Trail 65.