After Part 1, we return to RAF Bodney to the point where the RAF had pulled out handing Bodney over to the US forces. From now on, it would be the home of the USAAF 352nd FG, its P-47s and P-51s.

Famed for the blue-noses on their P-51s, there would be high successes but there would also be many tragedies along the way.

Formed previously in September 1942, the 352nd Fighter Group (FG) composed of three Fighter Squadrons (FS): 328th FS, 486th FS (previously the 21st PS) and 487th FS (formally the 34th PS). Their journey had been both long and difficult, using elements of two squadrons who had previous battle experience in the Pacific theatre. The new 352nd would move through a series of training camps and bases across America, serving as part of the US Air Defence force before deploying overseas. From Mitchel Field, they transferred to Bradley Field (Connecticut), Westover Field (Massachusetts), Trumbull Field (Connecticut) and onto Republic Field, New York before eventually leaving on the Queen Elizabeth arriving a week later at Bodney on July 7th 1943.

Arriving via Greenock and the Queen Elizabeth, the ground echelons of the 352nd were deposited at Watton station where they were taken by truck to RAF Watton. Pleasantly surprised by the far nicer accommodation blocks they had been used to, their joy was to be short-lived as Bodney was perhaps even worse than the original training camps they had endured back home.

Whilst the surrounding woods had been utilised for aircraft dispersal, the base was in need of an upgrade if it was to be used successfully. These improvements included the addition of steel mat and pierced-steel planking hardstands, additional taxiways and more roads constructed of both macadam and concrete. The men of the 352nd commuted daily from Watton carrying out repairs and improvements until such time as the airfield was more or less ready for occupation and they moved in.

During its time, Bodney would have two T2 hangars and five Blister hangars, accommodation would continue to be limited, allowing for around 1,700 men of mixed rank. Eleven accommodation sites were spread round the north and east of the main airfield, which included two communal sites (site 2 and 3) and two sewage works (sites 12 and 13). There were no WAAF accommodation blocks and due to initial shortages of Nissen huts, nearby Clermont Hall (originally a grand plastered brick Italian style building built by William Pilkington in 1812 as Lord Clermont’s hunting lodge*1) was ‘requisitioned’ and flying crews moved in, it was a complete change and total luxury compared to other bases and camps used by either the RAF or USAAF. However, following a visit from an Air Inspector, the stay was short-lived and the airmen moved back to the basic hutting of Bodney, even after strong protests from Group Commander, Lt. Col. Joe Mason.

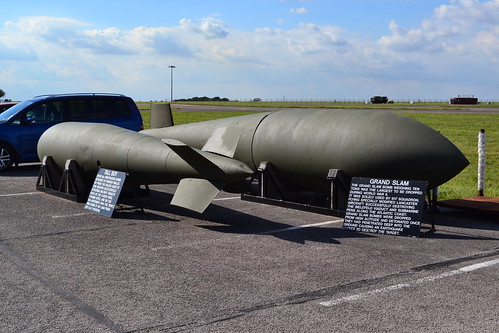

Master Mark II glider tug at Bodney, during airborne forces Exercise ‘SNAFFLE‘ © IWM (H 31737)

During this time manoeuvres regularly took place in the local area, and between August 9th and 11th 1943, one such exercise was conducted near to Newmarket, an exercise that involved both Polish and Canadian divisions opposing each other in mock attacks. During exercise ‘SNAFFLE‘, Master Mark II glider tugs used Bodney airfield whilst dropping a range of supplies such as petrol, ammunition and ordnance to illustrate both the usefulness, and importance of such activities. This made an interesting change to Bodney and something else for the crews to focus on.

It wasn’t long however, before the first P-47s were to arrive at Bodney, and at last flying could begin again with training flights started very soon afterwards. However, maintenance and flying operations were arrested by the lack of equipment, spares and aircraft – all very typical of the build up of US squadrons across the UK. As morale sunk, a special visitor arrived at Bodney, that of Capt. Clark Gable along with a film crew who were documenting the lives of American Fighter Squadrons involved in the European war.

A line up of P-47 Thunderbolts including (PZ-T,) “Little Evey” and (PZ-Z) “Pistol Packin’ Mama” at Bodney. (IWM FRE 2795)

On September 9th 1943, some two months after their arrival, the 352nd flew their first mission. An uneventful patrol over England’s eastern coast between Southwold and Felixstowe. For the next few mission, even those into enemy territory, similar conditions were found, the enemy were not seen and flak remained low. However, this did not mean the 352nd were casualty free.

On 13th September 1943, Lt. Arthur Eaker was killed in a local flying accident, the groups first, then on the 14th, Lt. William Alm disappeared whilst in flight over the North Sea. His aircraft P-47D (#42-22531) was thought to have been lost due to mechanical failure, he was never found.

It wasn’t until the 10th October that the pilots of the 352nd got to fire their guns in anger, when they encountered a flight of Bf-109s near to Hertogenbosch, Holland. The first kills were recorded, but it was not to be all plain sailing. Four days later on the 14th (‘Black Thursday‘), the Luftwaffe changed tactics and hit the escorts as they crossed the coastline. Leaving the bombers unescorted to their targets in Germany. Once away from their ‘Little Friends’ the bomber formations were decimated by Me-110s – something need to be done.

With more mission to Germany and escort duties, the 352nd began to cut their teeth and become battle hardened. By the turn of the year they had completed 38 missions with the loss of ten aircraft. The pilots of the 352nd had now twenty-two enemy aircraft as confirmed ‘kills’, but five of their own were killed and two others had been made prisoners of war.

A new year and new directives for fighter squadrons. in order to achieve total air superiority pilots were instructed to hunt for the Luftwaffe and destroy them whenever the opportunity arose. Every aircraft destroyed on the ground now counting as a battle credit, the same as an aerial kill. In addition, fighter squadrons were now given designated ‘zones’ to protect, and once the bomber stream had passed through their zone, the fighters were free to roam at will. The gauntlet had been thrown and the US pilots were hungry for rewards.

Early 1944 saw these directives put into action. ‘kill’ rates began to rise, but along with it casualties also mounted. By February the war-weary P-47s were looking tired and the new P-51 began to appear. The Ninth Air Force taking first pickings with Don Blakeslee, (Trail 46 and Trail 50) formerly of the ‘Eagle Squadrons’ becoming the first US squadron to have the mighty Mustangs. It wasn’t until March 1st, 1944 that the 352nd would receive their first P-51s, with seven being delivered and duly handed over to the pilots of the 486th FS at Bodney.

A battled damaged P-51 Mustang (PZ-S) of the 486th FS, in a Blister hangar at Bodney. (IWM- FRE 2803)

It would take just eight days for the Bodney crews to mark their first Mustang ‘Kill’. Capt. Ed Gignac, in P-51B ‘PZ-W’ (#43-7022), shooting down a Bf-109 in battle that saw both P-51s and P-47s of the 352nd participate.

April saw more changes and new arrivals, by now there were two squadrons of P-51s at Bodney, a new sound reverberated around the grassed airfield and with it came more new directives, As many squadrons were equipped with a mix of aircraft, it was beginning difficult to tell them apart in the hectic skies. Coloured noses, wing tips and fins were rapidly becoming markings of individual squadrons and those in charge realised that a standard form of scheming was now necessary for this new and innovative way of distinguishing squadrons.

The blue nose was born, and Bodney’s Blue-nosed Mustangs were soon to be seen at low-level attacking airfields, locomotives, vehicles, troop columns and other similar ground targets.

In May, whilst acting on escort duties for a raid over Brunswick, the group shot down 27 enemy Bf-109s and FW-190s with the loss of only one aircraft. This action earned them a Distinguished Unit Citation, for taking on a “numerically superior force of German interceptors” continuing on until lack of ammunition and fuel forced their withdrawal.

The 352nd went on to support the Normandy invasion, an operation that proved to be a fatal tragedy for one pilot in particular, Lieutenant Bob Frascotti.

Robert Frascotti next to his P-51B, 43-6685, named ‘Umbriago’ . At 21 years of age he was killed on his final mission before returning home. (Photo – Marc Hamel)

D-Day began early for the 352nd, the night sky was dark and to assist the take off temporary runway lights had been lit. Preceding Frascotti were his compatriots of the 486th FS. During the take off, one of the preceding aircraft struck a light causing the entire collection to extinguish. In the moments that followed, Frascotti and his wing-man, Lt. Carlton Fuhrman, were plunged into total darkness. Unable to see, the two were now committed and carried on, Fuhrman slightly behind Frascotti. Within seconds of them leaving the ground, there was a sudden and massive fireball in front of Fuhrman, a fireball that was the result of Frascotti striking the new, and as yet unfinished, watch office. His aircraft, fully armed and fully fuelled, became a fireball that lit-up the night sky, and one from which Frascotti would not survive.

Blinded temporarily by the flash, Fuhrman fought to prevent his aircraft stalling as he flew through the flames and on out into the night sky, struggling to orientate himself and unable to register his instruments due to the blinding flash. Behind him, Frascotti’s burning wreck lit up the field, one of the 352nd’s finest had been killed in a total and needless tragedy. The only saving grace from this was that every other aircraft taking off after Frascotti was able to see, a guiding light some say, and so prevented other tragic accidents from happening that night. This was the young 21 year old’s final mission, his 89th, and on completion he would have been returning home.

During D-Day the 352nd flew 116 sorties, reigning death and destruction down on the German forces below, other casualties were to follow, but none until now, as destructive and heart rendering as that of Frascotti.

The Watch Office after being hit by Frascotti’s P-51 on the morning of D-Day. (© 352nd FG, USAAF)*2

After Normandy, the 352nd went on to support the breakout at St.Lo and the airborne assault in Holland. As autumn led into winter, the temperature dropped and the weather took a dramatic turn for the worse; with heavy snow and cold winds across the continent, as the ground forces held out on the Ardennes forest knew only too well. The 352nd, like many other squadrons, were to help support the paratroops, being moved on a short-term basis to Belgium (Asch (Y-29) and Chievres (Y-84)) to join the Ninth Air Force earning themselves the French Croix de Guerre on New Year’s Day 1945.

A week earlier, on Christmas Day 1944 a second tragedy was to befall the 352nd, one that would take the life of another one of the 352nd’s finest. The squadrons highest scoring pilot at that time, Major George Preddy, a hero to many of the airmen and ground crews at Bodney, flew into an American Flak barrage put up by the US Army’s 12th Anti-Aircraft Group. His plane was hit and whilst his canopy was seen to be ejected, no chute appeared, and his body was found still in the wreckage of his beloved P-51. The news of Preddy’s death stunned the celebrations at both Asch and Bodney, no-one could believe that such a daring and brave pilot could have been lost, let alone lost to friendly fire.

April would see the 352nd return to Bodney, where they continued operations until May 3rd 1945. Their final move on November 4th would take them home to the United States, a move that left Bodney empty and a legacy that would be hard to follow. The 352nd had flown 420 missions, losing 118 aircraft with 70 pilots killed. They had been awarded 13 DSC’s, 31 Silver Stars, 336 DFCs, 1304 Air Medals and 42 Bronze Star Medals. The Group had created 52 ‘Aces’, 28 of which had achieved the status in air-to-air combat, accounting for 505 aircraft in the air with Major George Preddy achieving 27 of these himself.

With that departure Bodney fell silent, it closed very soon after the war in Europe ended on November 26th 1945, reverting back to farmland soon after.

Today Bodney falls next to the British Army’s STANTA training ground and as such parts are a military site. Some structures can easily be seen from the main road, B1108, with signs warning of MOD activity are everywhere. The original water tower and pump still serve the camp, a few air raid shelters exist and some buildings on the camp. Hardstands can be seen in the woods but little from the road itself.

The watch office is accessible (on farmland) where there are also a few other buildings to be found, including number of Type 22 pillboxes, many are derelict. The main army base is on part of the former accommodation site, with a memorial outside the gate dedicated to 352nd FG and associated units.

Many of the buildings that were in existence were pulled down in 2012/13 due to increased vandalism and their heavy use for Rave parties. As a result even less now stands visible telling the incredible stories of this forgotten airfield.

Sources and further reading.

*1 Norfolk Heritage Explorer website, accessed 15/8/18

*2 Photo via www.controltowers.co.uk

Frascotti’s story is told in more detail in Heroic tales.

Preddy’s story is told in more detail in Heroic Tales.

Walton, D. “Northumberland Aviation Diary” (1999), Norav Publications

Freeman, R. “The Mighty Eighth“, (1986), Arms and Armour.

There is a website dedicated to the 352nd with a link to the superb ‘Bluenoser’ magazine.